By Anna Willi

Interdisciplinary research can be daunting. It forces us to look beyond our expertise, to leave our comfort zone, to embrace those white areas on the map of our knowledge. But as new physical boundaries seem to be created all around us, it is more important than ever to keep an open mind, and interdisciplinary research forces us to do just that. It breaks up boundaries, opens up pathways to collaboration and renders shared features visible. Crucially, it can prove very fruitful for difficult research questions for which we rely on tricky evidence.

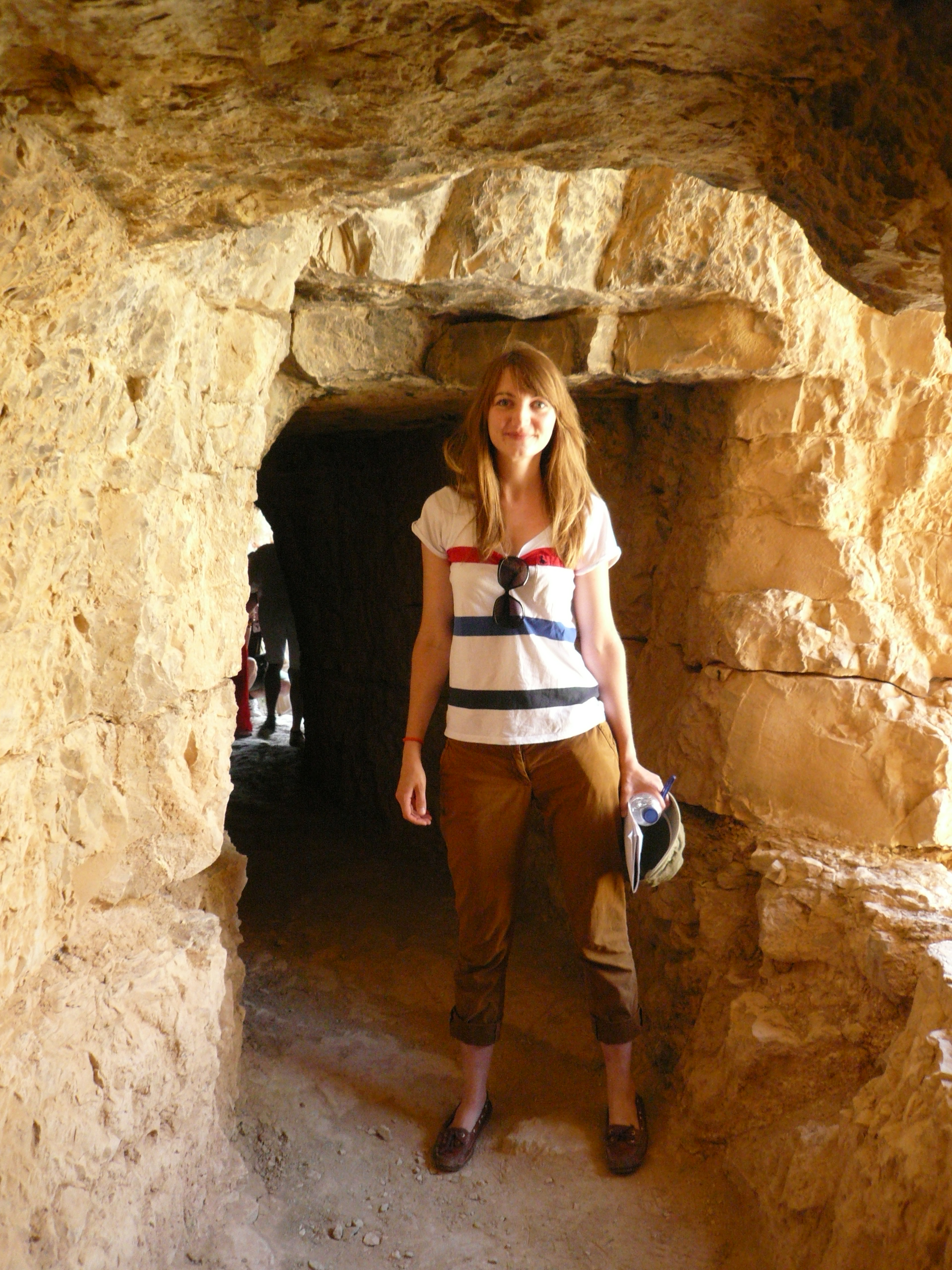

Anna deciphering a milestone inscription

The potential of this kind of approach is what has always motivated my research questions. When I started studying Latin Literature and Linguistics at the University of Zürich (Switzerland), I soon felt that by studying texts alone I was missing something, so I chose Ancient History and Classical Archaeology as minors. Ever since, I have been convinced that combining written and material evidence opens up new perspectives and allows us to ask new and intriguing questions. LatinNow uses an interdisciplinary approach to ask a number of such questions, and I am excited to be joining the team as a Research Fellow for Germania superior.

Germania superior is my home province, as it were. I grew up in Switzerland where I studied and wrote my PhD-thesis at the University of Zürich. For my PhD-thesis, I combined literary, epigraphic, juridical and material evidence to investigate the use and performance of irrigation in Roman western Europe. This research has left me with a strong awareness of the way in which people shape their environment, and for social and economic factors in this process. It is however the second focus area of my work that has me particularly excited about working with LatinNow: Epigraphy. I have been lucky enough to collaborate in a number of epigraphic projects since being an undergrad, including fieldwork that took me as far as Bulgaria and Cyprus. Most recently, however, I have mainly worked on inscriptions in Germania superior, for the new edition of CIL XIII.

Anna inside the Albarracin-Cella aqueduct

Inscriptions will be central to my research for LatinNow, and in my opinion they are a particularly fascinating kind of evidence. They are at the same time textual and material, and because they have not been copied numerous times over the centuries, they provide a window into the past that feels very immediate. Unlike the literary texts we know from school, inscriptions also come in various shapes and size. We find them on stone altars, pieces of leather, wooden tablets, bronze votives, drinking cups, bread and brothel walls. They were incised, scribbled, scratched, stamped and painted, they were conceived and written by people from all walks of life – and they can to some extent betray the linguistic reality in which their writers lived.

In Germania superior, this reality must have been rather diverse. Covering parts of modern Germany, Switzerland and France, the province was established under the emperor Domitian to comprise areas that had previously been part of Gaul and under Roman rule for some time, but also a stretch of the very edge of the empire along the German limes, where military presence was strong. Its population included people with Italian, Germanic or Celtic heritage as well as soldiers from other parts of the empire. Various languages must have been spoken in the streets of Mogontiacum, Argentorate or Augusta Raurica. However, our written evidence hardly does this diversity justice: with a few exceptions, to our knowledge the language commonly used for writing was Latin (though it sometimes contains traces of other languages in it). This makes literacy an important factor in studying the spread and use of Latin in Germania superior, and this is where new insights can be expected from the combination of epigraphic evidence with material evidence of writing equipment such as styli or ink pots. One particularly exciting part of my work with LatinNow will be to contextualise such finds within the epigraphic landscape.

The inscription of Togirix

Grasping language use without being able to ask speakers about it is less than straightforward. We may never know why the owner of a 2nd century villa near Bern decided to adorn the walls of their cryptoporticus with inscriptions that contain Greek, Gaulish and Latin language material (AE 2004, 991-995), or which language a certain Togirix from Eburodunum, who has a Celtic name and set up a dedication for Mercurius, Apollo and Minerva in Latin, spoke with his parent Meta (CIL XIII 5055). But looking at social and other phenomena that define this part of the Roman empire, there are other questions that we can ask. What role did Latin play in this multilingual environment and how did it come to play this role? How did different kinds of settlements, the diverse population and military presence influence the spread and use of Latin? And how is it different from what we know about Roman Britain or Spain? I look forward to delving into such questions, and to breaking up boundaries, opening up pathways to collaboration and rendering common features visible as part of an international and interdisciplinary team, collaborating to investigate a part of complex history that we all share.