By Anna Willi

Do we think that the Roman dead might be perceptive to a message from the living today? Because I think some of them may be interested in this…

It has always struck me how much the Romans thought of their dead as being part of their living world, and how they included them in that living world by honouring their memory through rituals. You may have heard that the dead were fed milk and wine on certain days of the year, sometimes through holes or pipes in their graves. You may also know, and have chuckled at, Ovid’s description of night-time bean throwing to appease unfriendly spirits that appeared during the Roman version of Halloween, the festival of the Lemuria in May (Ovid, Fasti, 5.421ff.). You may even have raised an eyebrow or two in appreciation of the trusts that were set up to guarantee the maintenance of burials and yearly gifts to the dead in eternity (see e.g. CIL III 703 from Philippi, Macedonia). The perhaps most touching result of this interactive approach to the afterlife is the way in which the Roman dead seem to talk to us from their grave, through the inscriptions on their tombstones: ‘stop here, traveller, and read about me and my life!’ (see e.g. CIL XIII 7070 from Mainz, Germania superior, where the deceased laments that he was killed by a slave).

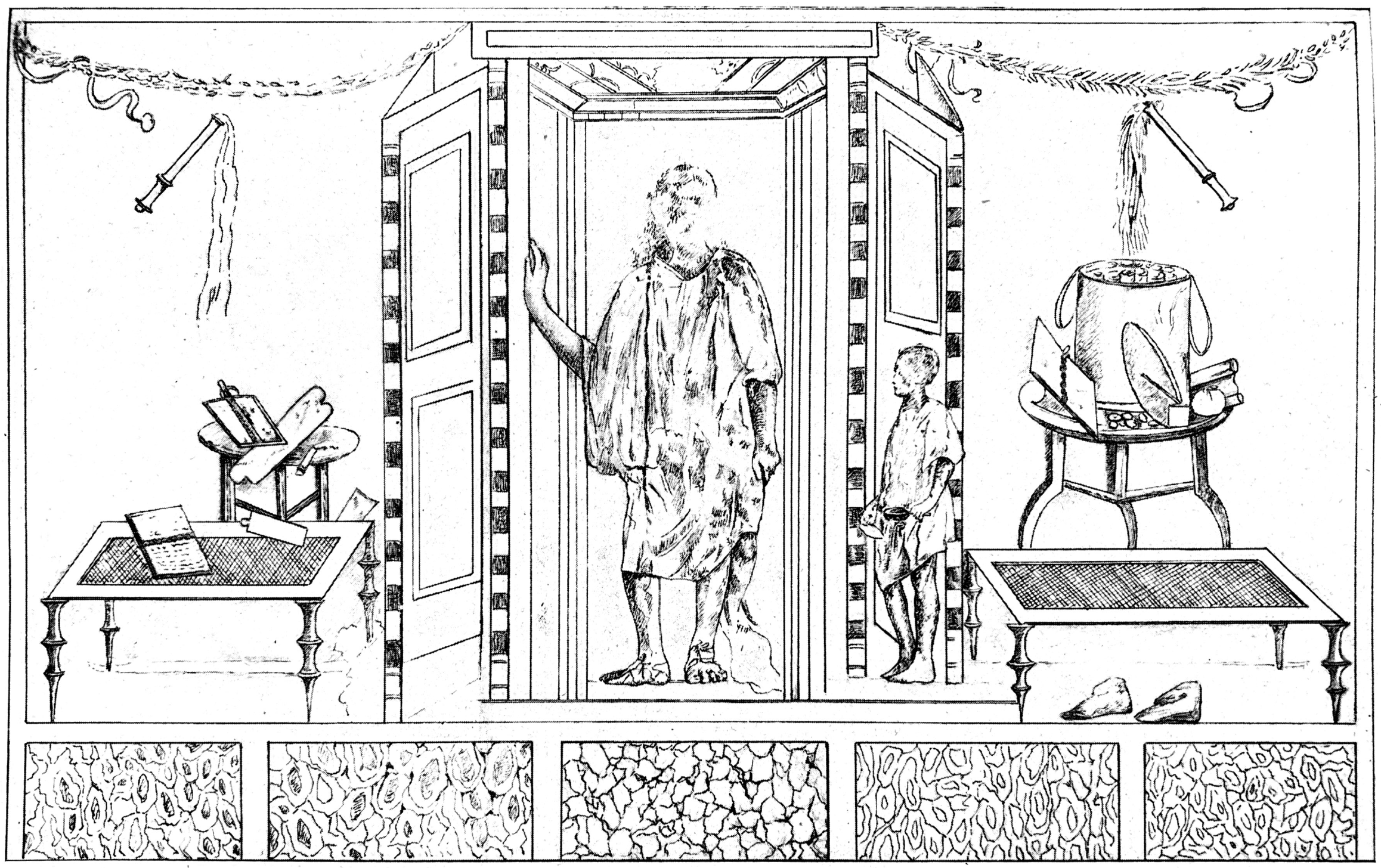

It was very important to the Romans that their memory was kept alive, and inscriptions and imagery on funerary monuments was used to express or shape this memory. I think of depictions on funerary monuments as a kind of iconographic blurb about the deceased, one that was also ‘legible’ for those that were unable to read. In most cases, there was little space for images and the scenes and items featured must have been chosen carefully. Interestingly, some of the dead seemingly wanted to tell us: ‘look, I had writing equipment!’

This week I attended an online conference at the University of Pécs, Hungary, that was all about the depiction of writing equipment on Roman funerary monuments (check out their ‘Scroll in Hand’ project here). Funerary depictions of writing equipment are particularly well (but not exclusively) known from the Danube provinces and the Greek East. Writing tablets, scrolls and writing sets containing pens and inkwells are particularly common, and they are sometimes shown on their own and sometimes in use. This is great news for us researchers working on Roman everyday writing because it gives the objects we know through archaeological finds some context and we can learn a lot from such depictions about how these objects may have been used (e.g., no tables, and no quills either!). But can we also learn something about the significance of writing for the representation of the dead?

Sometimes there is a clear professional connection, for example when people are shown or described as teachers or as accountants (this applies to both men and women), or if they were officials or magistrates who would have dealt with a lot of ‘paper’-work. But in some cases, the inscription does not mention the deceased’s occupation, or no inscription is preserved at all. In such cases it is difficult to know if writing equipment was in fact used by the deceased during their life time, or whether its depiction had a symbolic function. Literacy and writing represented education but also more generally social and professional status. The symbolic function can be even more abstract, with a scroll representing a legal document or act such as the manumission of a slave and thus the free status of the person shown holding it.

Where detailed writing sets or individual writing implements are shown, or where people are shown in the act of writing, we can at least assume that it somehow related to the identity of the deceased. It was clearly important to them, whether they were literate or not, whether they used writing for their occupation or not. It was so important that they wanted to be remembered as writing in eternity. It has not been an eternity yet, but I think those writing dead men and women would be pleased to know that we’ve seen their writing equipment – and took a long hard look at it, too!

These funerary images of dead people writing, and wishing to be remembered as such, are very moving. Thanks for the attention and what you have found.