By Francesca Cotugno

One of the aims of the LatinNow project is to combine the analysis of writing with the material analysis of writing implements and epigraphic media. By drawing upon different strands of evidence – from archaeology, linguistics and history – we hope to get a clearer picture of the specific circumstances that were involved in the take up of Latin during the initial phases of Roman occupation of the north western provinces. In this post I want to draw attention to recent research on Roman lead ingots that were mined and cast along the eastern and western banks of the Rhine because they highlight the kind of insight – as well the conundrums – that this combined approach can yield.

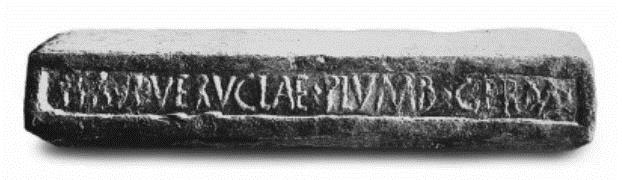

Figure 1: Ingot from Saintes-Mairies-de-la-Mer (picture from Eck 2015)

Ingots are fascinating because they are impressed with names which offer us vitally important information about the imperial control of mineral sources as well trade and other cross-cultural dynamics in the early Roman Empire. Take the first ingot, which was found in the commune of Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer in the Rhone delta close to the Mediterranean coast. It is impressed with the words FLAVI VERVCLAE PLUMB(um) GERM(anicum) ‘Germanic lead, product of Flavius Verucla’, along its side whilst the top of the ingot is impressed with the words, IMP(eratoris) CAES(aris) ‘property of the Emperor Caesar’. Now let’s look at the second ingot, which was found miles further north on the north east reaches of the Rhine in Bad-Sassendorf (see figure 2). This has part of the personal name L. FLA[—] moulded on one side, and on the other side there is another version of the same name L. F. VE. It is possible that both of these formulations are the same as those of the Rhone delta ingot: L. FLA[vi Veruclae plumb. Germ.] and L. F[lavi] VE[ruclae plumb. Germ.]. In fact, the isotope analysis of the lead confirms that both ingots came from the same mine in the area of Sauerland (c. 120km from Cologne) and that they were cast in the first century CE.

Figure 2: Ingot from of Bad-Sassendorf /Heppen (Image from Eck 2015)

If we turn to the historical evidence we can see that there would have been a very narrow time span (roughly from 7 BCE to 9 CE) when lead mines on the eastern banks of the Rhine would have come under Roman control (and would therefore have been subjected to an imperial toll) as the imperial mark suggests. The salient dates here are 7 BCE – the year in which Tiberius was summoned back to Rome from his campaign in the territories east of the Rhine, and September 9 CE – when 35,000 men, almost three Roman legions and their auxiliaries, were either slaughtered or enslaved at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest by an alliance of Germanic tribes. After the permanent withdrawal of the legions from the area to the east of the Rhine, the Romans would have been forced to look for mineral resources in Germania Superior and Inferior on the west bank of the Rhine

As we would expect, lead ingots dating from the period in which Caligula was emperor (37–41 CE) come from Germania Inferior, the area west of the Rhine. Two ingots that were found near the river Rhone, at Fos-sur-Mer and at Ile-Rousse, on Corsica, are interesting in this respect. The ingot from the Rhone valley has the following moulded mark, IMP(eratoris) • TI(berii) CAESARIS • AVG(usti) • (plumbum) GERM(anicum) TEC(-). This can be roughly translated as ‘Property of the Emperor Tiberius Caesar Augustus, Lead from Germany’ . The ingot from Corsica shows the following text: CAESAR • AVG • IMP • GERM • TECF. The last letter is smudged and is difficult to decipher.

Figure 3: Ingot from Ile-de-Rousse (picture from Raepsaet-Charlier 2011)

In both cases, TECF and TEC remain unexplained. LatinNow’s Special Adviser, Prof. Marie-Therese Raepsaet Charlier has carried out extensive analysis of these ingots which I can only summarise here. She suggests that TEC is not a Latin word but may be of either Celtic and/or Germanic origin. This is interesting because the isotope analysis reveals that the lead was probably sourced in the area of Mechernich, west of the Rhine. Therefore the mine would have been in the vicinity of an altar where the matres and matronae Textumehae (distinctive groupings of three female deities, both mothers and matrons) were worshipped, and may reflect the first element of their name. An alternative, possibly related, interpretation is also possible. According to this, TEC may be derived from the Indo-European root teg- ‘to cover’, found in Celtic tribal names like Tectosages, and found in a toponym of the area, Tectae. This root is thought to have given rise to the Celtic term, tecto– ‘possession, property’. According to both interpretations, TEC would be an example where Latin was combined with Celtic perhaps in order to integrate the imperial control of mining resources within the non-Latin context. Both interpretations are possible, but an explanation involving unknown abbreviations or a mistake in Latin may also be an option. We await further clues to help to solve the mystery!

Further Reading

Bode M., Hauptmann A. & K. Mezger (2009), ‘Tracing Roman lead sources using lead isotope analyses in conjunction with archaeological and epigraphic evidence—a case study from Augustan/Tiberian Germania’, Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 1: 177-194.

Long L. & C. Domergue (1995), ‘Le véritable plomb de L. Flavius Verucla et autres ingots. L’épave 1 des Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer’, MEFRA 197-2: 801-867.

Raepsaet-Charlier M. (2011), ‘Plumbum Germanicum: Nouvelles données’, L’antiquité Classique 80: 185-197.

Raepsaet-Charlier M. and Raepsaet C. (2013), Der in Tongern aufgefundene Bleibarren mit dem Namen des Kaisers Tiberius. In G. Creemers (ed.), Archaeological Contributions to Materials and Immateriality (Atuatuca 4). Tongeren, pp. 38-49.