A guest blog by Josy Luginbühl

LatinNow relies on brilliant researchers around Europe for its collaborative work. In this blog, Josy Luginbühl (University of Bern, Switzerland) tells us about her fascinating PhD research on writing equipment in female graves. Her data forms part of our set on Roman-period literacy which will be made available in a webGIS later this year.

Whether you are reading this blog on the train, at your desk or in your dentist’s waiting area, take a look at the objects around you: which of your belongings do you think represent you best as a person? Your favourite shirt? A certain book? Perhaps a reusable coffee cup, or your iPhone? And would you choose to take them to your grave? What may seem like a strange question to us today was quite normal in Antiquity. Grave goods were carefully selected and accompanied the deceased on their last journey. Depending on the social status, they could include tableware and cutlery, elements of clothing, tools and weapons.

As was pointed out by Janie in her recent blog about stationery, some people were buried with their writing equipment. Let’s for example have a look at the grave of a man from Roman Noviomagus, today Nijmegen in the Netherlands. He was buried around 90/95 CE with his spears and his shield and with a variety of writing implements: two styli, two wax spatulas, an inkwell and a ruler. In addition, there were numerous vessels made of valuable materials. He was probably a local aristocrat with a higher function in the local military camp. The connection between literacy and the military is well known and has been emphasised frequently: being able to read and write would have been an advantage for a military career and probably effectively a requirement for higher officers.

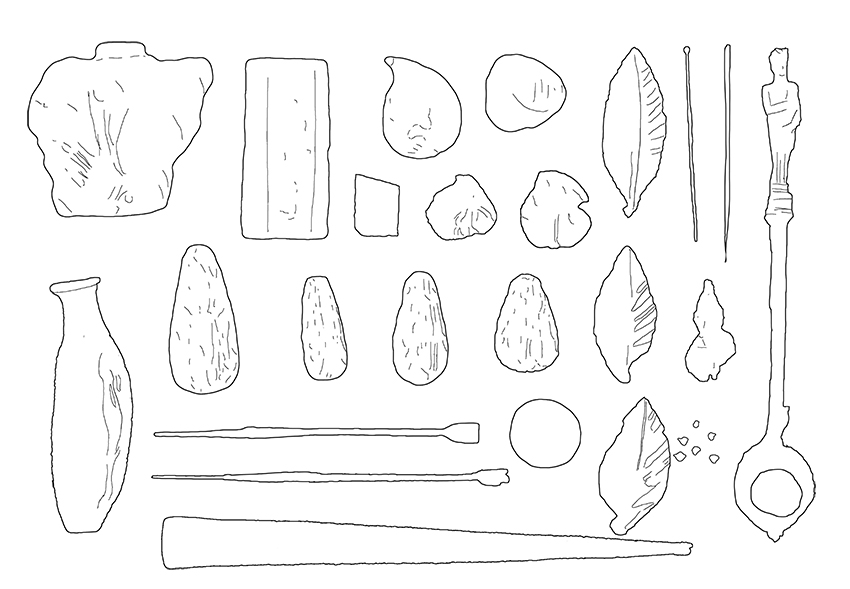

Perhaps more surprising is a grave from the second half of the second century CE from Aquileia (Italy). It contained a perfume bottle, a jewellery box, a fig, three chestnuts, four dates and four leaves, all made of amber, two hairpins and a distaff made of bone, as well as two bronze styli. The inscription on the corresponding sarcophagus tells us that this is the burial of Antestia Marciana, who died at the age of 12 and was buried by her loving parents. Small figurines such as the fruits were often given to children as lucky charms and dedicated to the gods when they reached adulthood. For girls this happened mostly on the eve of their wedding, as this event marked their passage from girl to woman. That the figurines were still in Marciana’s possession indicates that she was not married yet. While they are frequent grave goods for girls, the two bronze styli are remarkable because the written sources do not tell us much about the education or literacy of young girls.

While in modern Europe it would be unusual to be buried with a pen or a smartphone, writing equipment had a specific value in Roman antiquity. As an element of Roman culture, it was put in the graves of deceased individuals in the entire Latin-speaking West, and, as seen above, not only for men but also women and children. This fact was the basis of my doctoral thesis. I collected graves with writing equipment in Western Europe, that is the Latin-speaking part of the Roman empire (well, part of it, as Northern Africa was not included in my study). By analysing associated grave goods, the skeletal remains and the geographical and chronological pattern, I aimed to better understand who was in contact with literacy or aspired to an ideal of education. Our ideas of Roman literacy and education are mostly formed by the written sources and a focus on the city of Rome, and often the spotlight is on the male world. An analysis of burials with evidence related to literacy widens the focus and provides insights into life in the provinces and a social environment that is not imperatively the senatorial aristocracy.

Would you believe that there are more female burials with writing equipment than there are male?! This is not what we would expect from reading the written sources. They rather link literacy to the army, the (provincial) administration, trade or leisure of the upper classes – and to the male part of society. While women did not obviously play an active role in the military or administrative service, they were nonetheless part of this social environment, for example through their husband’s occupation or the location of their family home. The distribution pattern for female and male graves shows an emphasis on these spheres. Many graves with writing equipment are from military sites that are part of the limes (the frontier zone in the Germanies) or at least nearby. Others are from administration centres or situated next to important roads.

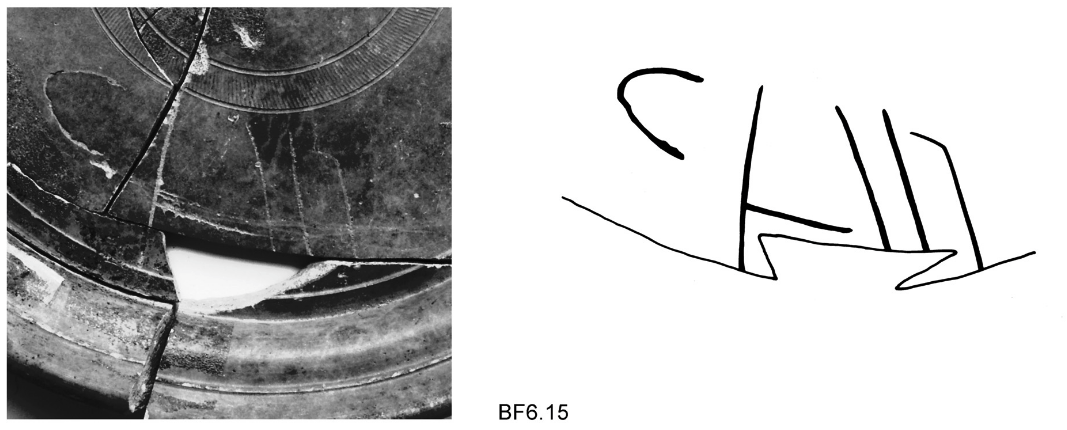

Only rarely have writing media such as (fragments of) papyrus scrolls or wax writing tablets survived in graves. Much more common are the actual writing implements, such as a stylus, inkwell or wax spatula. It is not always possible to say beyond doubt whether the buried person was actually able to write themselves, and if so, at what level. Sometimes, short inscriptions on grave goods, like a name scratched into a ceramic cup, suggest some degree of literacy of the deceased or a person close to them. Labelling one’s possession is not only useful in a modern flat share…

But even without clear proof for actual literacy, the selection of grave goods shows that this ability, or in a broader sense education, was an important and desirable ideal. This ideal is not only visible in the grave goods (and therefore no longer on display after the burial ceremony) but, as Anna has shown in her Halloween-blog, was sometimes part of the commemoration of the deceased for eternity on sarcophagi and tombstones, too!

Further Reading:

Brusin, G. (1937). ‘Regione X (Venetia et Histria). III. Aquileia. Ritrovamenti occasionali.’ Notizie degli scavi di antichità, 190–196.

Fünfschilling, S. (2012). ‘Schreibgeräte und Schreibzubehör aus Augusta Raurica. Mit einem Beitrag von C. Ebnöther.’ JberAugst 33, 163–236. <https://artefacts.mom.fr/Publis/F%C3%BCnfschilling_2012_[Schreibger%C3%A4t_Augusta_Raurica].pdf> (09.06.2022)

Koster, A. (2013). The Cemetery of Noviomagus and the Wealthy Burials of the Municipal Elite. Nijmegen.

Luginbühl, J. (2017). ‘Salve Domina. Hinweise auf lesende und schreibende Frauen im Römischen Reich.’ HASBonline 22, 49–72, <http://dx.doi.org/10.22013/HASBonline/2017/3> (09.06.2022)

Martin-Kilcher, S. (2000). ‘Mors immatura in the Roman world. A Mirror of Society and Tradition’, in: Pearce, J., Millett, M. and Struck, M. (eds), Burial, Society and Context in the Roman World. Oxford, 63–77.

Sealey, P. R. (2007). ‘The graffiti from Chamber BF6’, in: Crummy, N., Shimmin, D., Crummy, P., Rigby, V. and Benfield, S. F. (eds), Stanway: an Elite Burial Site at Camulodunum. London, 307–314. <https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-3299-1/dissemination/brit_24/06stanway5.pdf> (13.06.2022)