By Alex Mullen

Regina is one of the best known and loved characters from Roman Britain. She is a character in Minimus, had a replica of her tombstone in a South Shields’ carpark, appears in copies in the British Museum and the Great North Museum and features on the homepage of the Roman Inscriptions of Britain Online. She stars in the KS 2 materials we have been making with Classics for All in a new project to bring the Roman Inscriptions of Britain into Schools. She is indeed a ‘long-lived Queenie’.

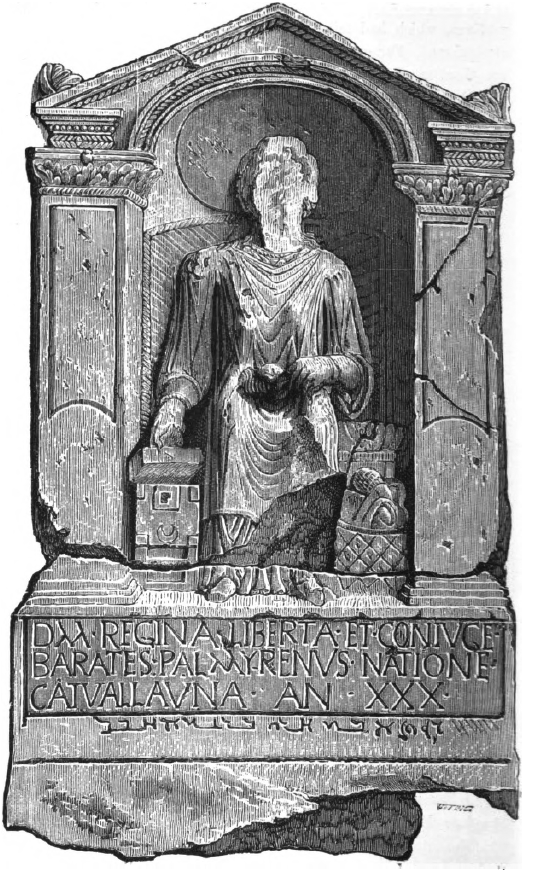

And yet we only know her from her second-century CE tombstone found at South Shields, near Newcastle, with its carved image and four lines of text (https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1065). We don’t even get to see her face as at some point someone deliberately erased it. Could it have been an angry ex-lover in the Roman period or vandalism in the post-Roman period? We’ll probably never know. Maybe this is one reason why we find her so appealing: we want to give her a face and a voice.

What do we know about Regina and her life? Regina sits in the centre of the large tombstone facing us in a wicker chair framed with a gabled structure and columns. She wears a long-sleeved robe over a tunic and jewellery, and around her head is depicted a large oval-shaped object, which has been called a ‘nimbus’. These are put around heads in images to indicate holiness and/or eminence, but we don’t really know what it signifies here. There’s a basket of wool on her left, she is opening a box with her right hand, and she holds a spindle and distaff in her other. This last feature is often found on the depictions of women from Roman Syria.

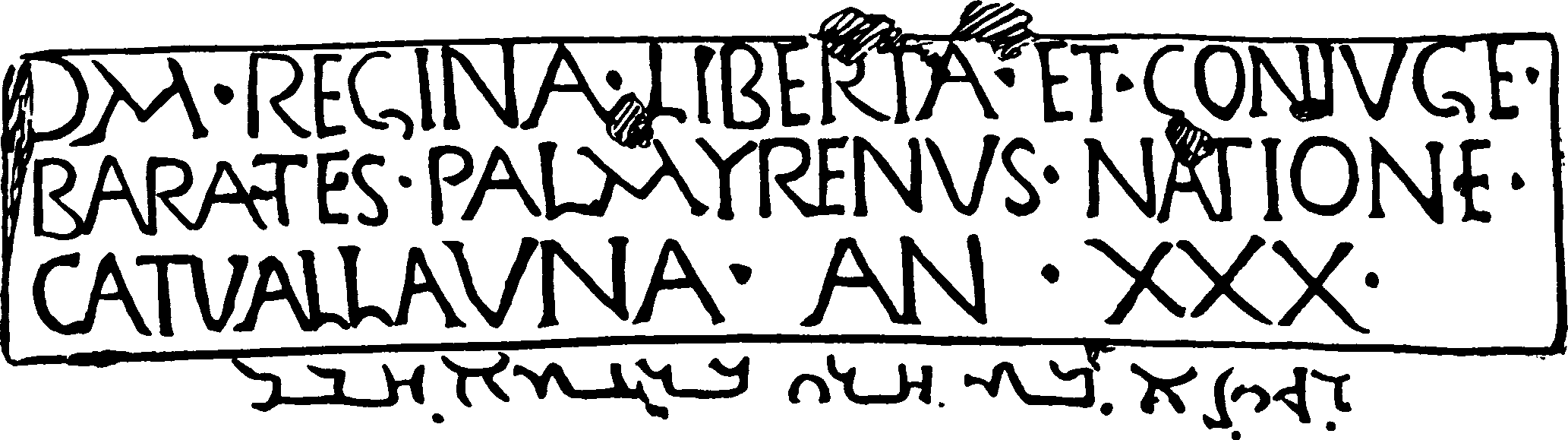

So how might Syria fit into Regina’s story? We have to turn to the text to find out more. DM opens the three lines of Latin. DM stands for dis manibus and is extremely common in funerary texts, it means ‘to the spirits of the dead’. Then we find out that Regina is from the tribe of the Catuvellauni and is a freedwoman (liberta) and wife (coniunx) of Barates. She died when she was only 30 years old (an(norum) XXX). Why was a Catuvellaunian female enslaved and why was she freed? Sadly we know nothing of the background to her changing statuses.

The monument was set up near the fort at South Shields, but neither of the two people mentioned are from north-eastern Britannia. Regina is from the tribe whose centre was at Verulamium, now St Albans, and Barates, her husband, describes himself as Palmyrenus ‘of Palmyra’. He has come all the way from Palmyra in Central Syria. He added something unique within the inscriptions from Roman Britain: a line of Palmyrene. Palmyrene is the dialect of Aramaic spoken in central Syria. Aramaic was a Semitic language widely spoken in the eastern part of the Roman Empire and was the mother tongue of Christ. It is written from right to left and says ‘Regina, the freedwoman of Barates, alas’. He perhaps felt that he had to express his grief in his first language. How did Barates find someone who could write Palmyrene so neatly onto stone? Did he add it himself or did an associate of his?

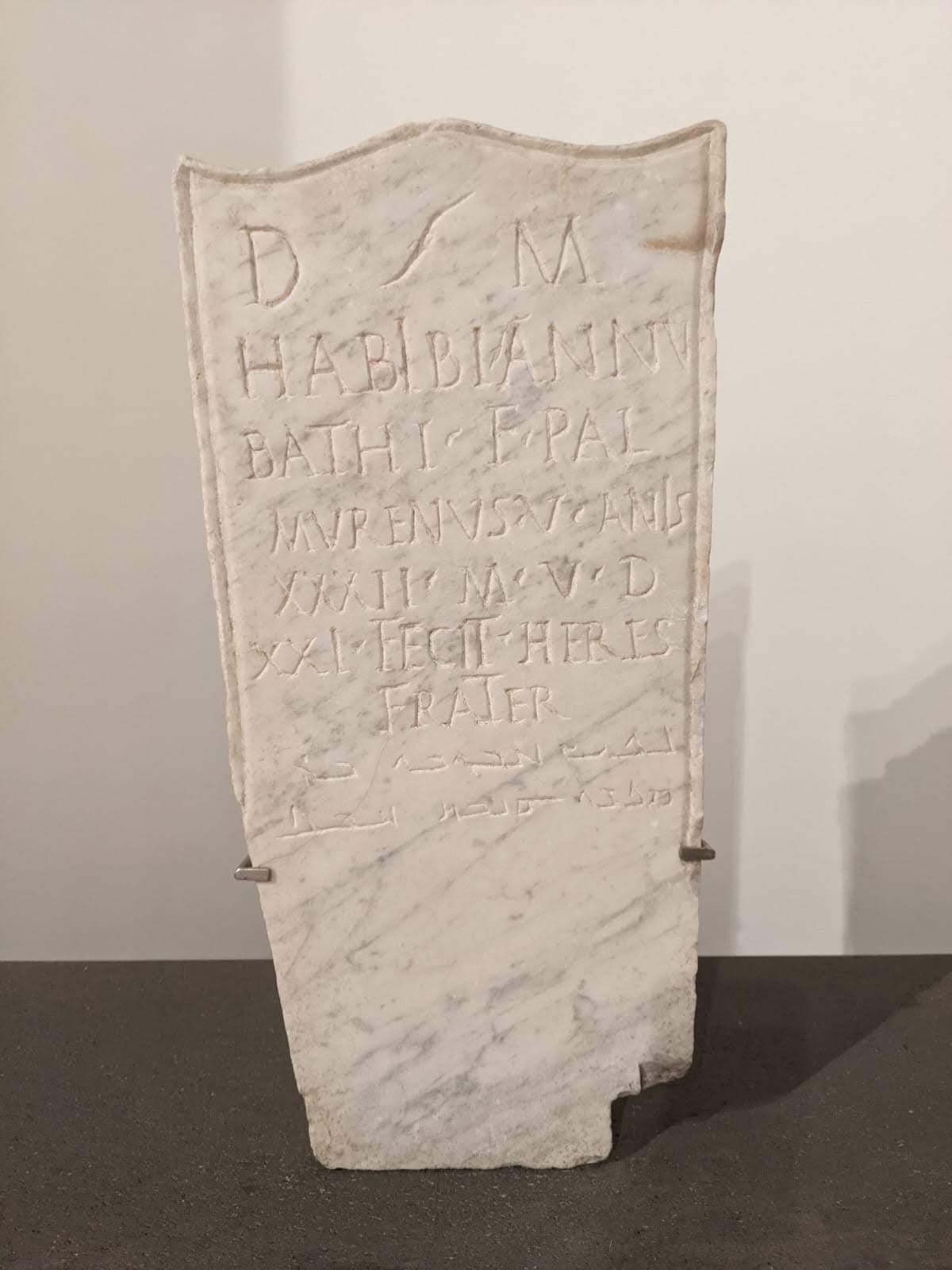

We know that the Roman army was diverse and drawn from all over the Roman world. Indeed the Palmyrenes were one rare group that sometimes included their homeland’s language (in this case Palmyrene) in their inscriptions in the Western Empire (usually other groups would use Latin (and sometimes Greek), no matter what their traditional local language). At Carvoran, further along Hadrian’s Wall in the second century CE there was an auxiliary cohort of Hamian archers, from Roman Syria, these would also presumably have spoken dialects of Aramaic as well as Greek and some Latin. At Corbridge there is even another Latin inscription with a Barates, also referred to as a Palmyrene (https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1171). This man died when he was 68 and is described as a vexillarius, which may mean he had been a flag-bearer in the auxiliaries or perhaps for a trading association. Barates is a common name in Syria so there is no certainty that this Barates is Regina’s husband, but the possibility is enticing!

To return to our text we can gather some more clues. The Latin isn’t quite as we expect it – and it looks as if interference from Greek may have caused the mistakes. So perhaps the first language of the writer was Palmyrene, then Greek, the lingua franca of the Roman East, then Latin. The Latin also exhibits something interesting in the term Catuallauna. This is not how we find the tribal name in Latin where it would be Catuvellauna. Interestingly the change in in the vowel from -a- to -e- in this linguistic context could be a Celtic sound change. So perhaps we have here a clue to the local pronunciation of Regina’s tribal name. Maybe she spoke British Celtic, perhaps alongside British Latin, and her pronunciation had passed on to Barates too.

The language of the monument, both the visual and the textual, can be deconstructed it into its elements: Roman Syrian, Palmyrene, British Celtic, Greek, Latin. But could people reading this in Roman South Shields pick these clues up? If only say 5% of the inhabitants of Roman Britain could read Latin, and the Palmyrene would have been read by many fewer, perhaps much of the message was lost. And what would Regina have felt about her monument and people scrutinizing it centuries after her death? Did she love Barates as much as he, apparently at least, loved her? Or was he her way out of slavery? Was the whole monument much more about Barates, and for his own flaunting of status? In the Palmyrene she is only referred to as a freedwoman and not Barates’ wife, why? And would she have appreciated being styled as a Roman Syrian woman who worked diligently with wool, as all good Roman women should?

Regina, or Queenie, a name that works in both Latin and Celtic, is a wonderful example of the diverse human history of Britannia. There is much more we wish we could know about her, but this eloquent monument is now all that remains of her short life.