By Dan Gray (University of Nottingham placement student)

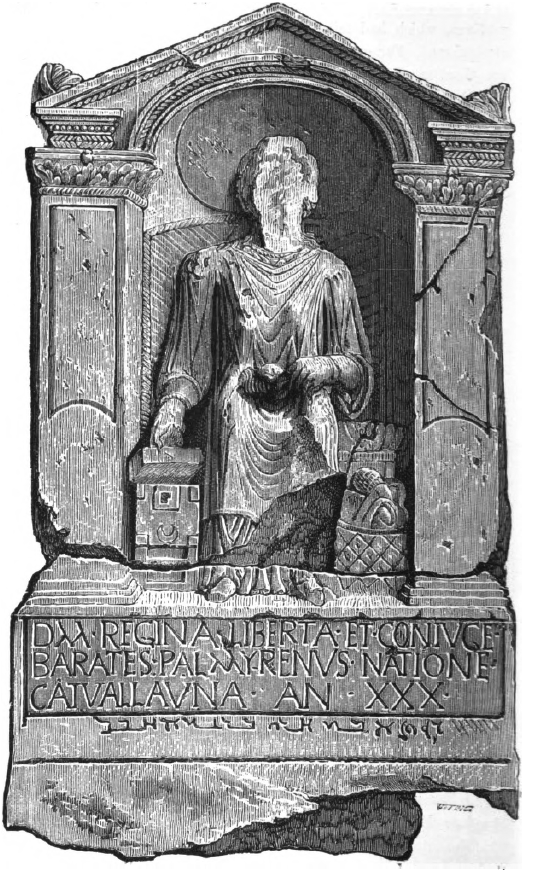

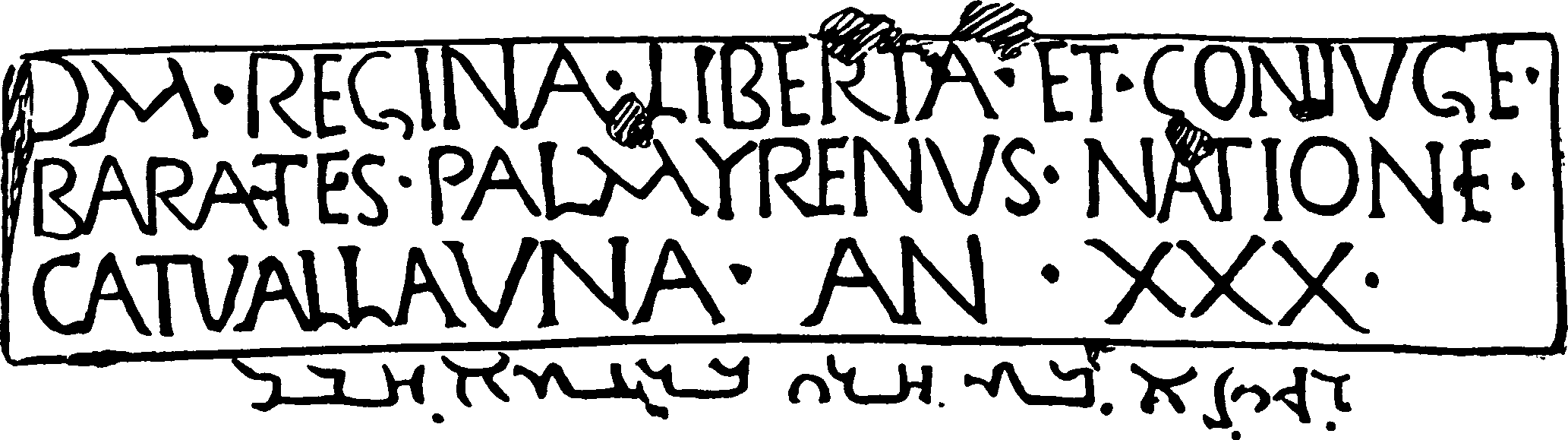

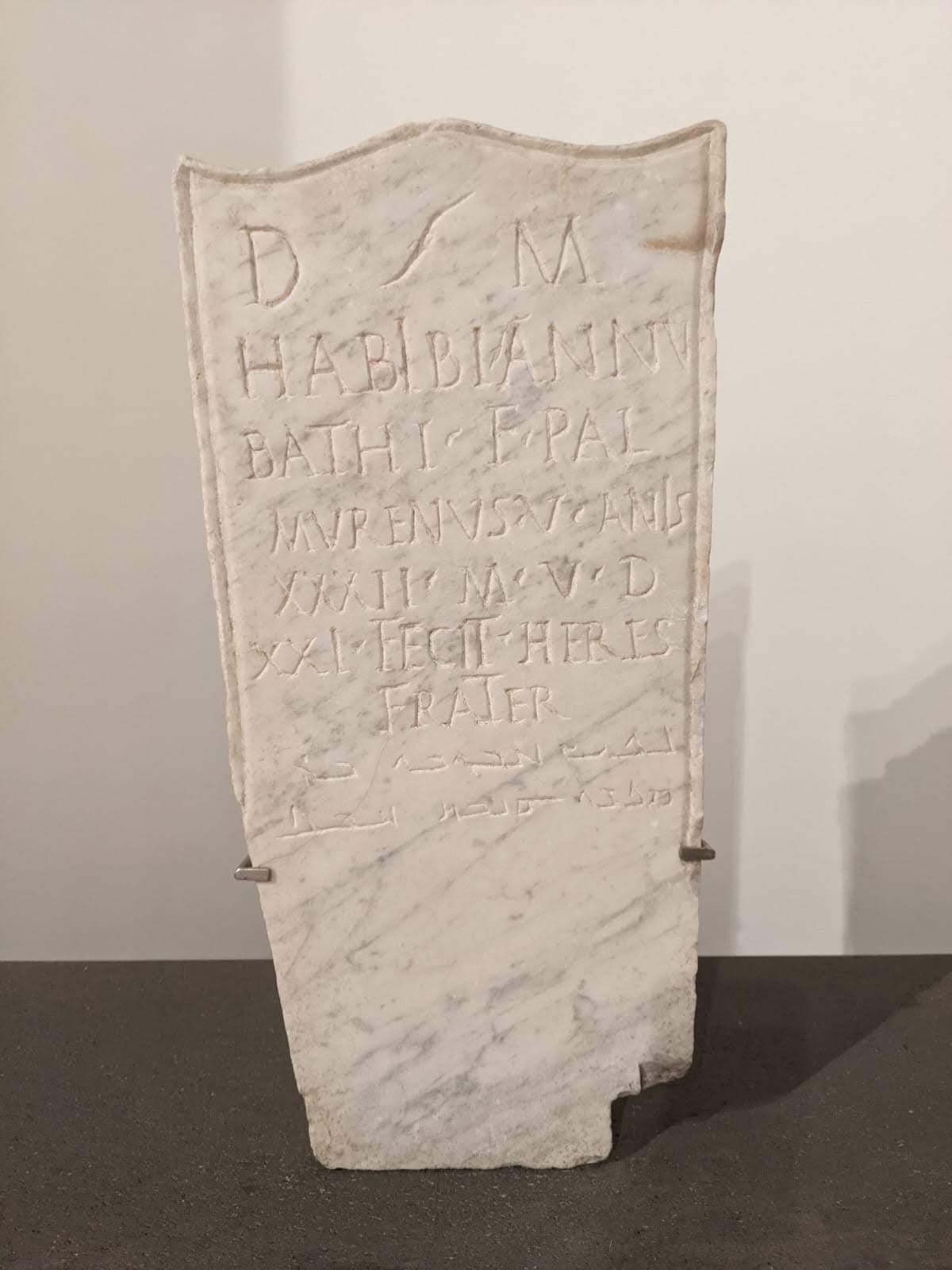

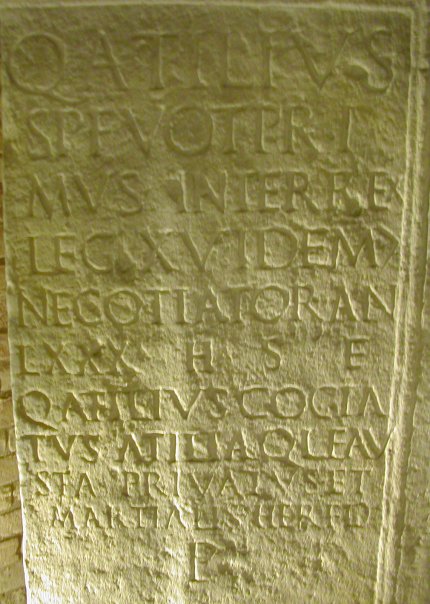

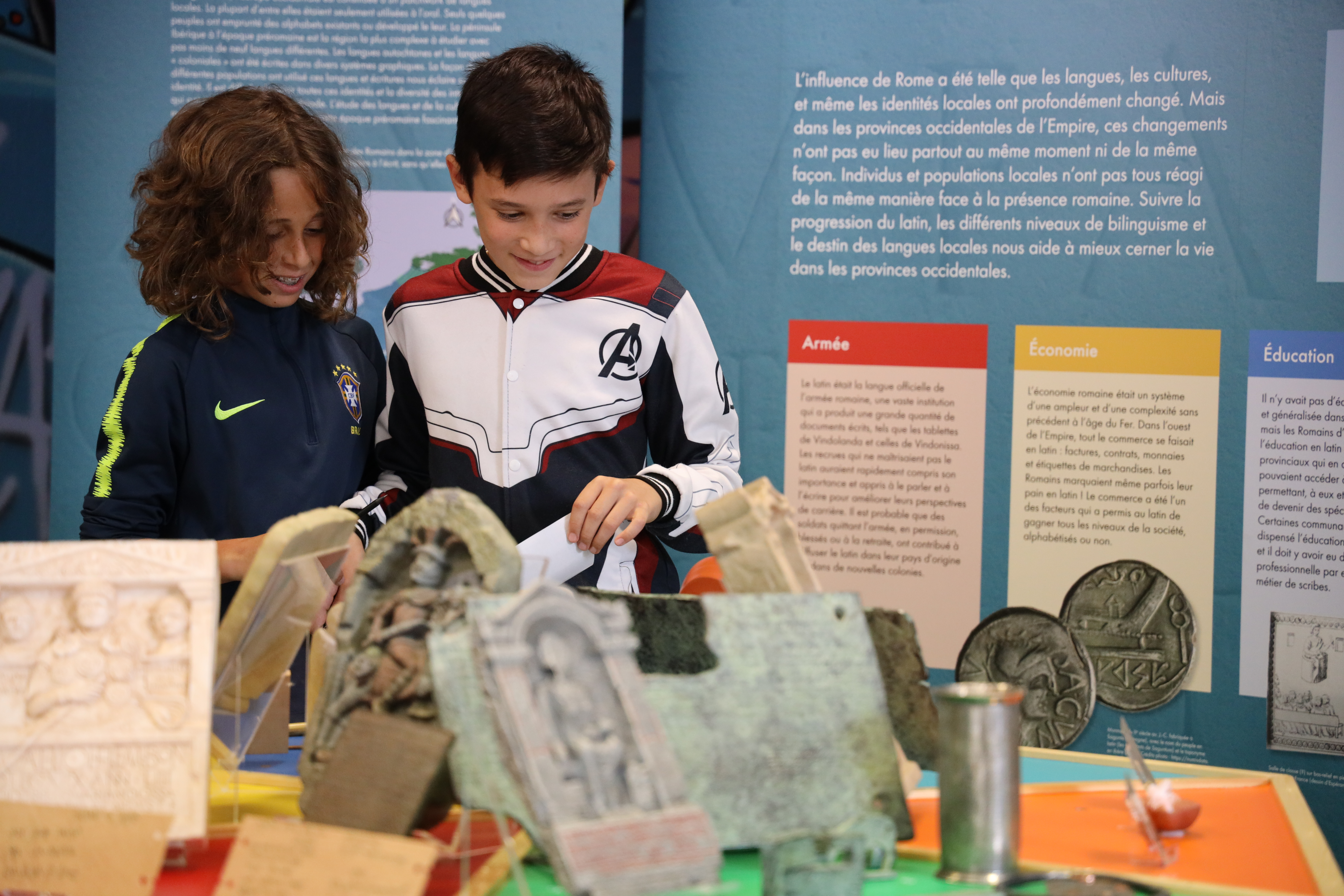

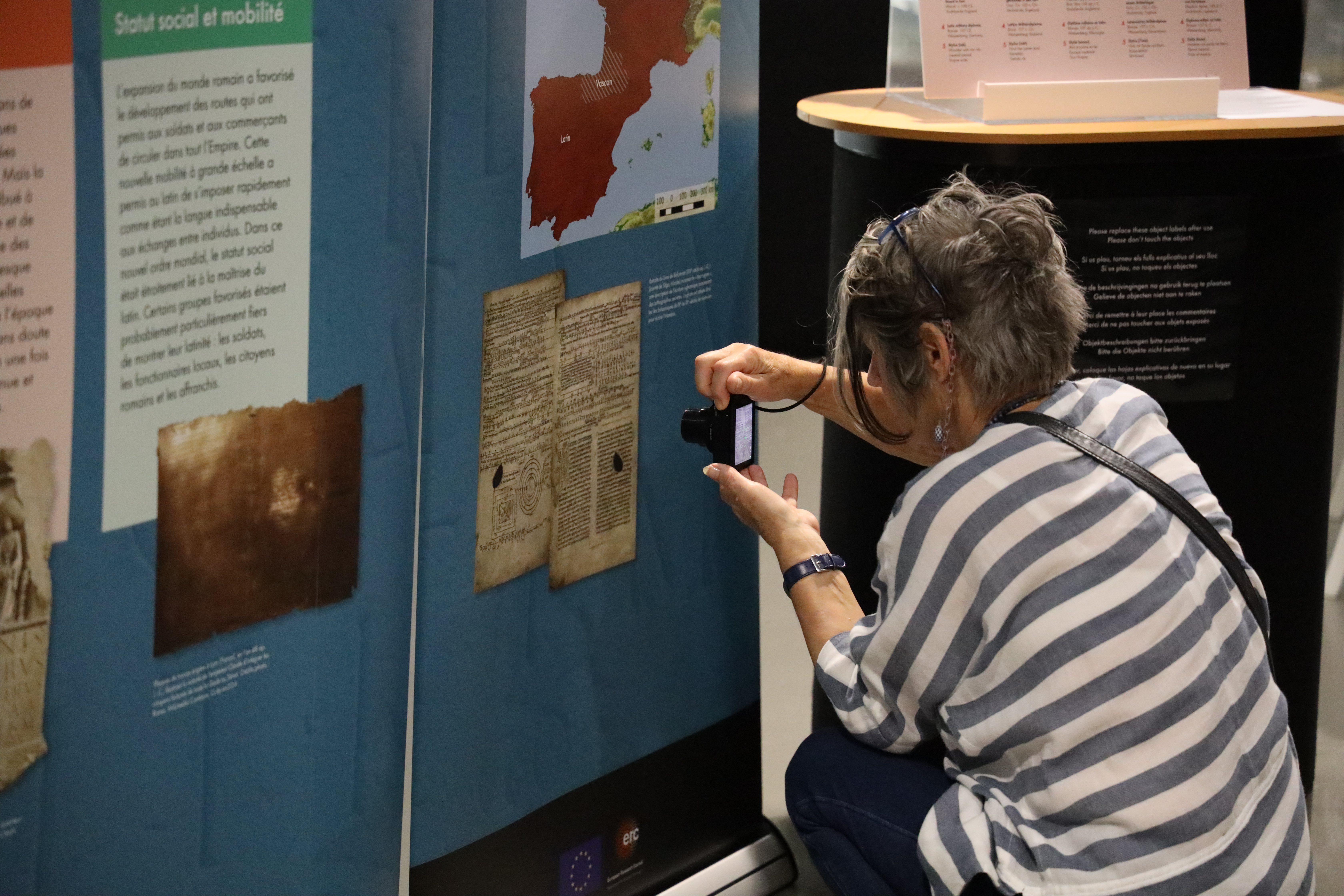

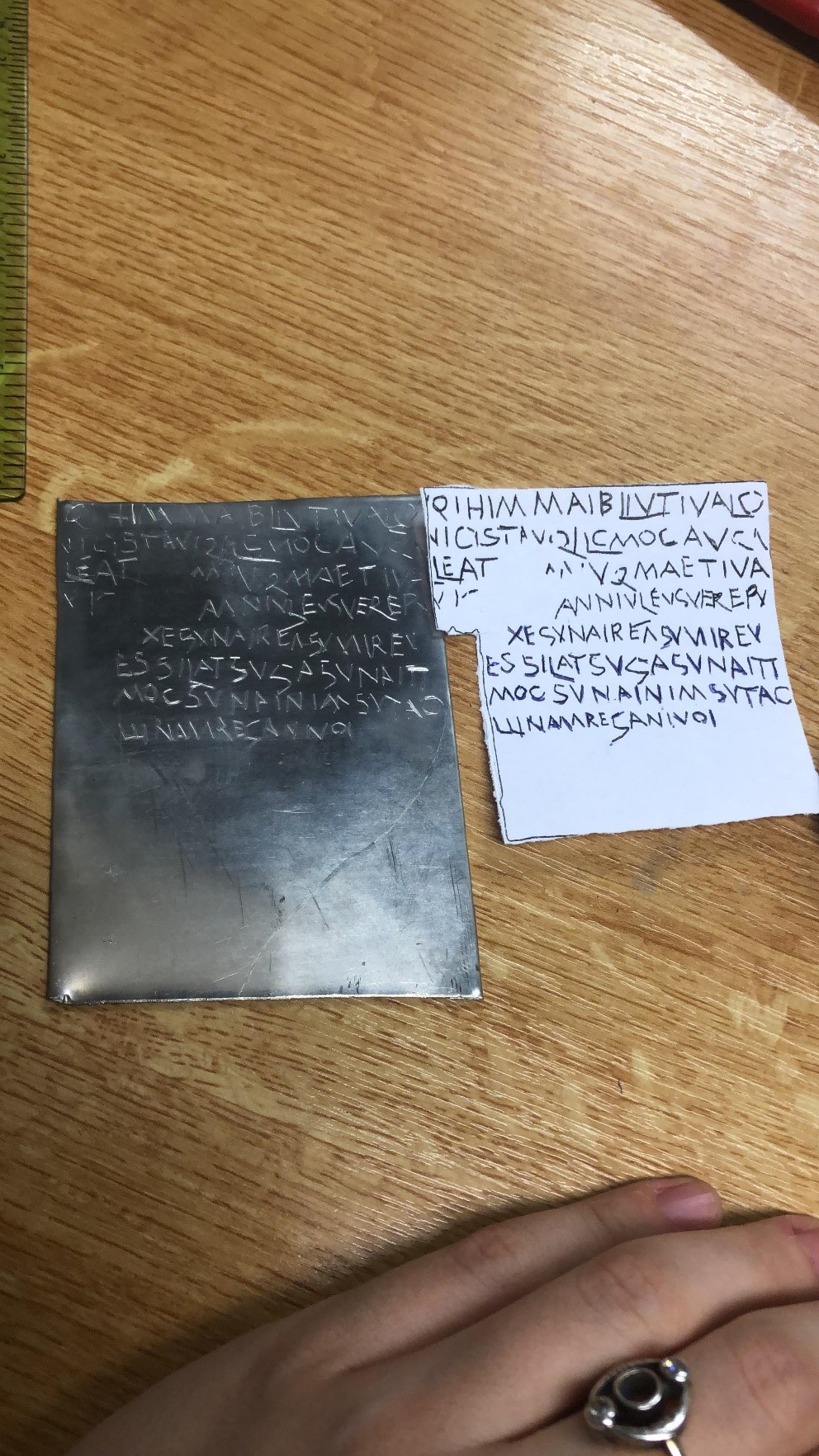

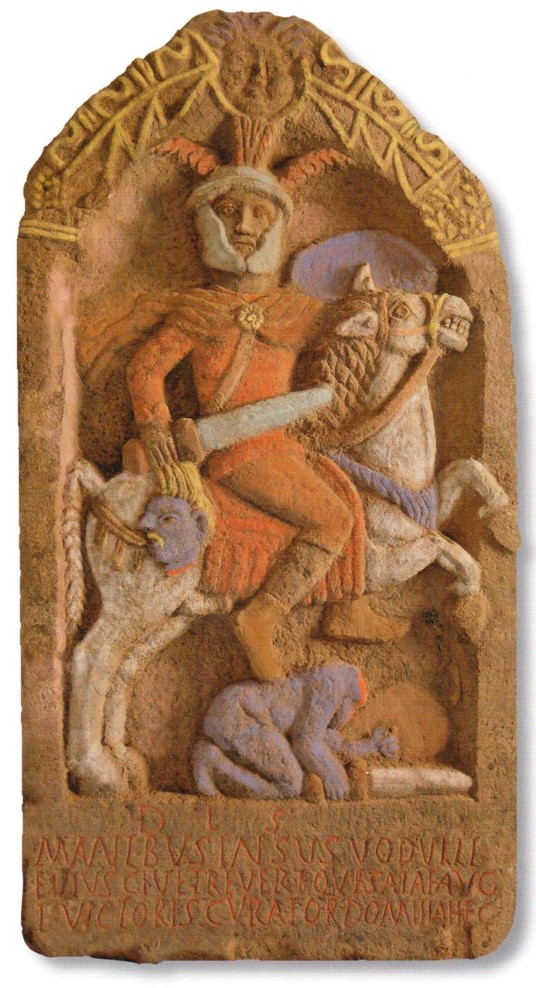

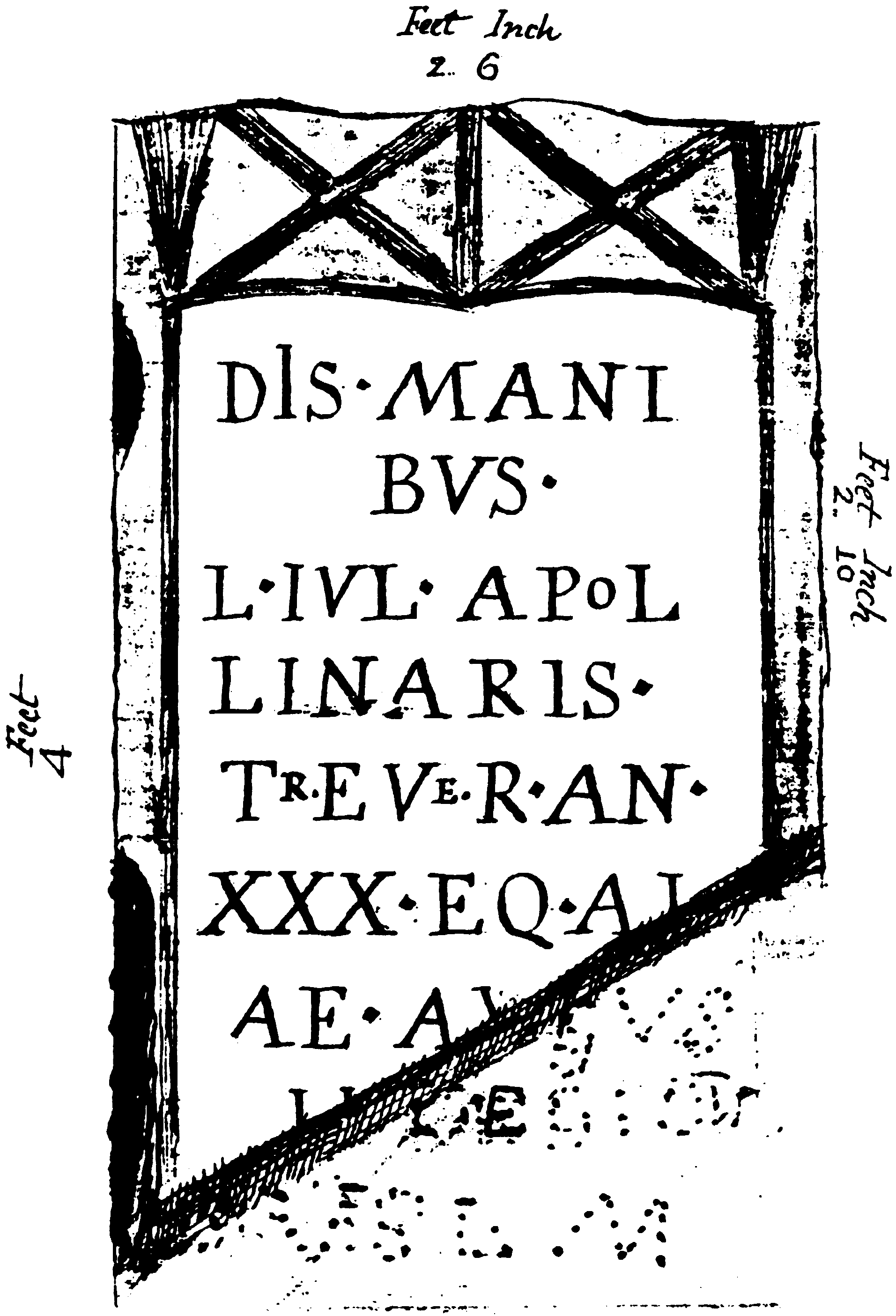

Over the course of my placement with the Roman Inscriptions of Britain in Schools project I have been fascinated by the objects and texts we worked with extensively, for instance the tombstones of Insus and Regina and the ‘Vilbia’ curse tablet. However, there were two inscriptions that intrigued me the most, namely, Vindolanda Tablet no. 185 and the Bloomberg Tablet no. 45. In the case of the Bloomberg tablet, found in the City of London, this showcases Roman life in Britain after conflict, namely Boudica’s revolt. Though it is not complete, it tells us about a trade deal involving provisions of food being transported from Verulamium (St Albans) to Londinium (London) in AD 62 (specifically: in the consulship of Publius Marius Celsus and Lucius Afinius Gallus, on the 12th day before the Kalends of November, i.e. 21 October AD 62).

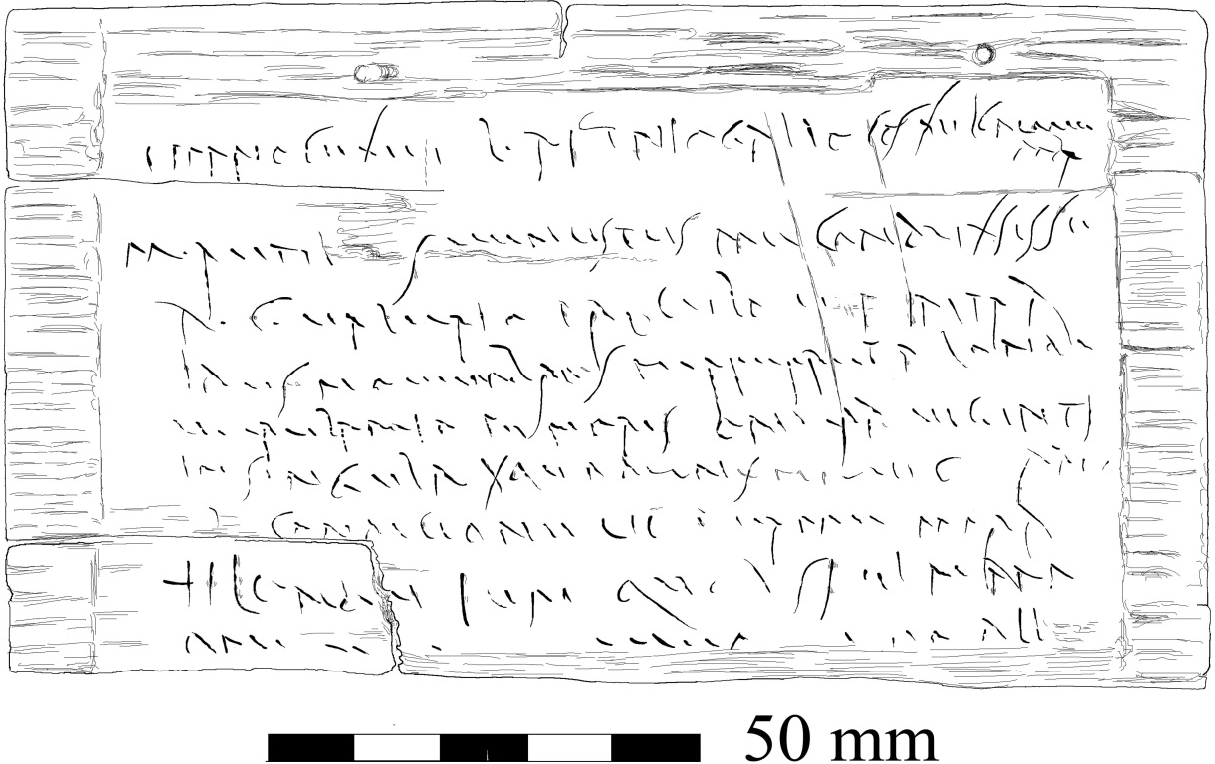

‘In the consulship of Publius Marius Celsus and Lucius Afinius Gallus, on the 12th day before the Kalends of November (21 October AD 62). I, Marcus Rennius Venustus, (have written and say that) I have contracted with Gaius Valerius Proculus that he bring from Verulamium by the Ides of November (13 November) 20 loads of provisions at a transport-charge of one-quarter denarius for each, on condition that … one as … to London; but if … the whole …’

Boudica’s revolt was quelled with Boudica’s death in only AD 61 therefore it seems significant that traders thought it was safe enough to transport a big cargo of provisions so soon after widespread revolt. This could show how quickly everyday life for an average trader in a frontier province might resume after conflict. Perhaps Britannia was not as destroyed as badly as we sometimes imagine or perhaps the inhabitants were used to recovering quickly from conflicts?

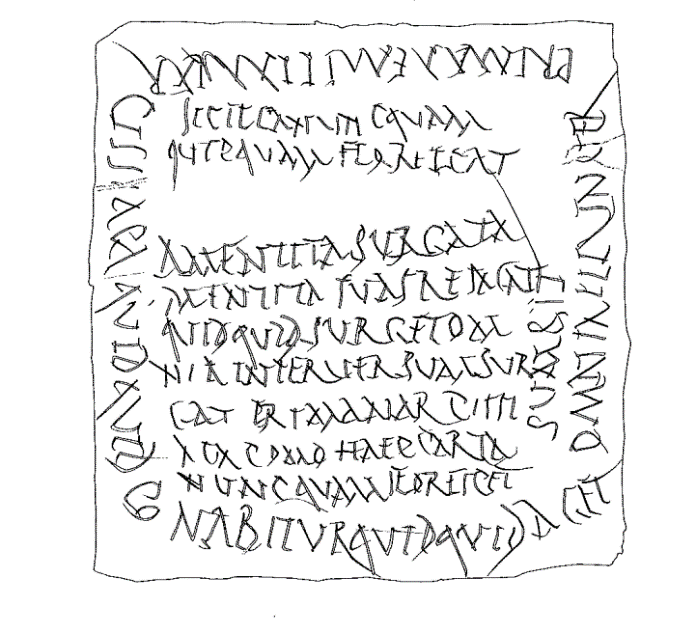

Bloomberg Tablet No. 45 ‘ Stylus Tablet’ © MOLA

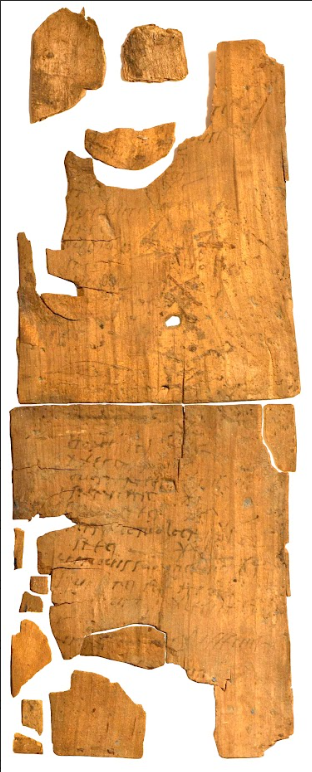

Vindolanda Tablet no. 185, from the Roman fort just south of Hadrian’s Wall, is somewhat similar to the Bloomberg Tablet, and although in this case we do not have a precise date in the text itself, the object can be dated to AD 92-97. The text is laid out in a format like a ledger of goods payments (for barley, wagon axles, wine, fodder, salt, vests etc.).

For lees of wine (?), denarii ½

July (8-13), at Isurium (?)

for lees of wine (?), denarii ¼

July (9-14), …

for lees of wine (?), denarii ¼

July (10-14), …

(lines 17-29) … 8 ..

for lees of wine (?), denarii ¼,

of barley, modius 1, denarii ½, as 1

wagon-axles,

two, for a carriage, denarii 3½

salt and fodder (?) …, denarius 1

at Isurium, for lees of wine (?), denarii ¼

at Cataractonium, for accommodation (?), denarii ½

for lees of wine (?), denarii ¼

at Vinovia, for vests (?), denarii ¼

of wheat, …

total, denarii 78¾

grand total, denarii 94¾.

What is usual about this account is that it mentions a series of place names: Isurium (Aldborough), Cataractonium (Catterick) and Vinovia (Binchester). The editors of the text wondered whether it was an account of expenditure incurred on a journey. The order in which Isurium, Cataractonium and Vinovia occur is the order in which they would be reached by a traveller coming from York to Vindolanda via Corbridge. This again reminds us that both people and these kinds of goods would be travelling constantly across the country. Who the travel was undertaken by in this text not clear, but the text gives us an insight into normal life and provisioning: the army, but also the local population, would need food and to fix their vehicles. This shines a light on the everyday life of the people living in Roman Britain, rather than the focus being on the battles that we tend to see in the Roman historical texts for the province. There would have been so many people involved across the province, and beyond, to keep the military garrison well provisioned with such a range of food and other goods. They especially liked the orangey-red pottery we call samian ware.

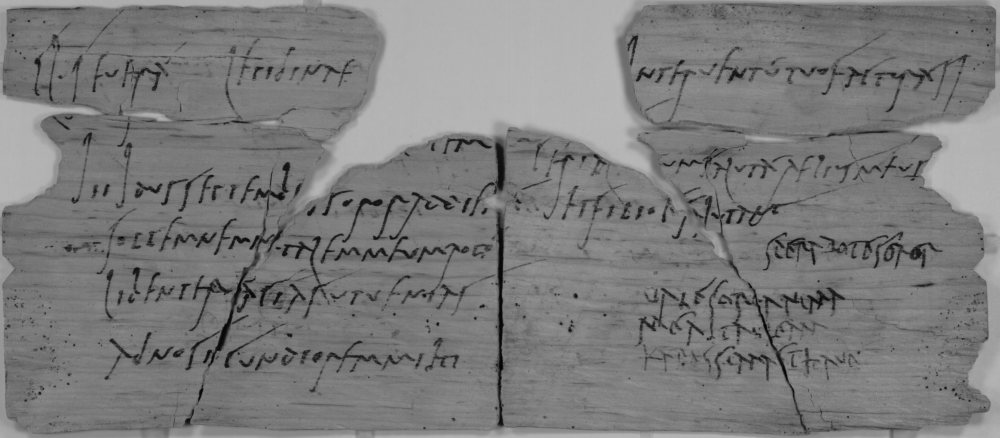

Vindolanda Tablet No 185, ink on wood © The Trustees of the British Museum

Another interesting point to consider is the mode of transport and the time it would have taken to move goods like this around. I would have thought with big quantities of goods that the transportation would have been quite slow. For instance, with the Bloomberg Tablet we know that they are heading from Verulamium to Londinium which according to the Orbis stanford site, ORBIS: The Stanford Geospatial Network Model of the Roman World, is about 35 kilometres and for which the transport of the twenty provisions suggested would take approximately 2.9 days in the Autumn using an ox-cart. With regards to the Vindolanda tablet, the journey between Vindolanda and York would have taken perhaps as many as 15 or so days. (You can choose various major Roman places on the ORBIS website and select mode of travel, time of year etc. I had to find the nearest big place and extrapolate to Vindolanda…) And en route, over long distances and at a slow pace, the traders would have been vunlerable, so might at some times an din some areas have needed military protection.

The objects we have focused on for the RIB in Schools project have been interesting in how they make us think outside the traditional militaristic narratives and focus instead on the range of different experiences and voices within the Roman Empire. For instance, the two tablets discussed here provide an insight into the life of traders and how they go about making their living through trading with the civilian and military populations.