Over the Christmas period we are celebrating the publication of two books in the LatinNow trilogy. The project has produced or supported the production of several books, including our Manual of Roman everyday writing (vol. 1 and vol. 2), but the three volumes which are being published in the Oxford Studies in Ancient Documents series by Oxford University Press represent, with our Open Access web GIS, the core research output of our project. They are the result of a huge effort of the LatinNow team but also the expertise of a wide network of colleagues across Europe and beyond.

The two appearing in December are the result of workshops held in Autumn 2018 and Spring 2019. Virtually none of the chapters look much like the papers delivered, since we used those thought-provoking workshops as the beginning of a long process of collaboration, which entailed debates, revisions, translations, and reworking. This required patience, especially through the pandemic, and we’re so grateful for the dedication of the contributors. We are delighted that all the books are Open Access, funded by the European Research Council.

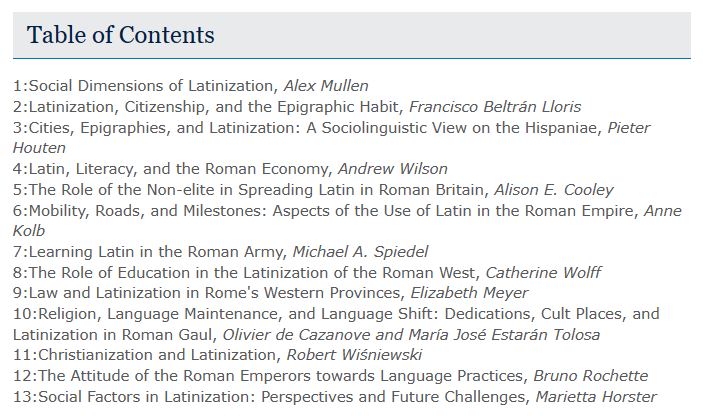

The first to appear will be Social Factors in the Latinization of the Roman West. To our knowledge it is the first English-language edited volume devoted to Latinization, which, oddly enough, is a relatively overlooked topic. Historians have noted it has been ‘taken for granted’ and viewed as an unremarkable by-product of ‘Romanization’, despite its central importance for understanding the Roman provincial world, its life, and languages. This volume aims to fill the gap in our scholarship. We took a multi-disciplinary and thematic approach to the vast subject, tackling administration, army, economy, law, mobility, religion (local and imperial religions and Christianity), social status, and urbanism. The contributors situate the phenomena of Latinization, literacy, and bi- and multilingualism within local and broader social developments and draw together materials and arguments that have not before been coordinated in a single volume.

The result, we hope, is a comprehensive guide to the topic, which offers a mix of some more familiar syntheses and more experimental work. The sociolinguistic, historical, and archaeological contributions reinforce, expand, and sometimes challenge our vision of Latinization and lay the foundations for future explorations. We don’t agree with all of the arguments in the volume, notably that on the lack of influence of the auxiliaries of the Roman army in Latinization, but we present our different perspective in the introduction (and in much more detail in the final book of the trilogy). We hope that the volume will act as both a state-of-the-art of the subject and the starting point for further debate and research.

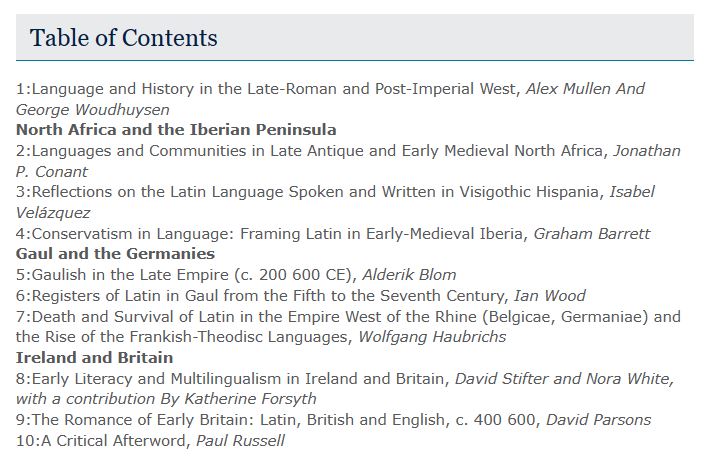

The next book to appear will be Languages and Communities in the Late-Roman and Post-Imperial Western Provinces. Our scoping of the international academic activity on later Roman and post-imperial sociolinguistic histories and our subsequent workshop demonstrated that the subject is still comparatively understudied and that there was even further potential for progress on sociolinguistics and interdisciplinary collaboration than we had assumed. A deeper understanding is crucial to any reconstruction of the broader story of linguistic continuity and change in Europe and the Mediterranean, as well as to the history of the communities who wrote, read, and spoke Latin and other languages, and it clearly had significance for the LatinNow project in terms of understanding the embeddedness, or not, of Latin socially and regionally. The volume offers a study of the main developments, key features and debates of the later-Roman and post-imperial linguistic environment, focusing on the Iberian Peninsula, North Africa, Gaul, the Germanies, Britain and Ireland. The chapters collected in this volume help us to consider (socio)linguistic variegation, bi-/multi-lingualism, and attitudes towards languages, and to confront the complex role of language in the communities, identities, and cultures of the later- and post-imperial Roman western world.

Perhaps even more than the Social Factors volume, we see this volume as a starting point for further research. The introduction sets out some of the key areas on which we think there is scope for further developments and why we think the sociolinguistic and interdisciplinary analyses of the medieval period have not advanced quite as far as for ancient world studies. I couldn’t have brought this volume together without the erudition and support of my colleague at Nottingham, George Woudhuysen.

We will be bringing the third book of the LatinNow trilogy into the world next year. This final volume, co-edited with the wonderful Anna Willi, is more ‘team-written’ than a traditional edited volume and will encapsulate our thoughts on how we can best explore life and language in the Roman west and will present the latest research on Latinization, local languages, and literacies in the provinces in all their regional complexity. It was supposed to be the volume that appeared first, but various parts had to be put off until our data were ‘finalized’ and we have been battling our perfectionist tendencies… It will be last major publication of the LatinNow project, and we hope it will be worth the wait.

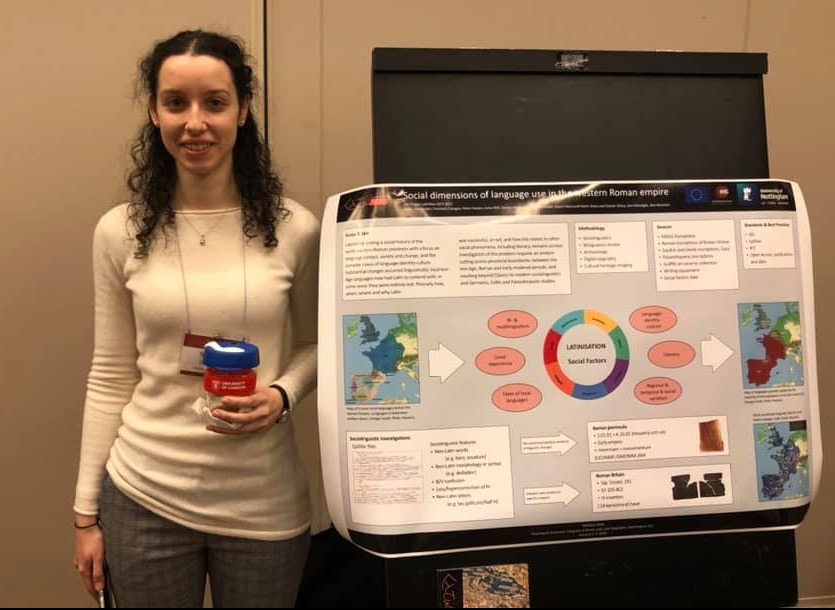

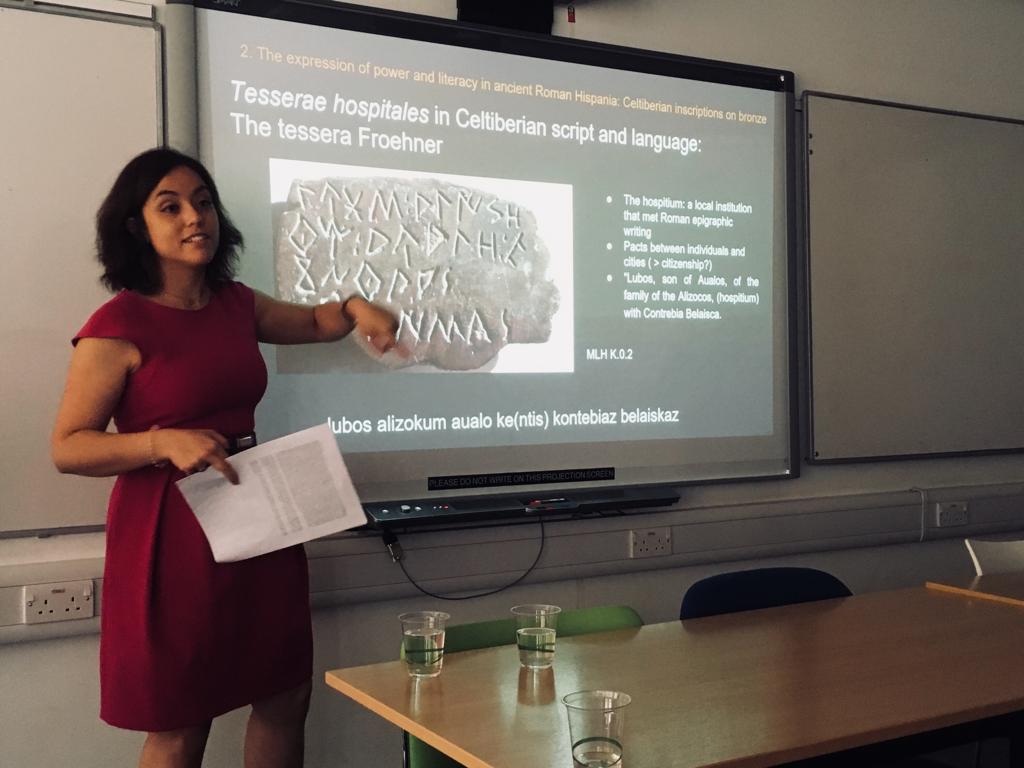

nd presented the only material culture-based paper. There followed a lively discussion and I am happy to report the audience was fascinated by our scope, approach and methodology, especially the application of modern linguistic theory to ancient linguistic material, and the integration of digital humanities. The room was packed – impressive for 8 am on 2nd January. Significant amounts of coffee were consumed.

nd presented the only material culture-based paper. There followed a lively discussion and I am happy to report the audience was fascinated by our scope, approach and methodology, especially the application of modern linguistic theory to ancient linguistic material, and the integration of digital humanities. The room was packed – impressive for 8 am on 2nd January. Significant amounts of coffee were consumed. Each morning, during a session appropriately called Posters and Pastries, I would stand next to our glossy creation (click

Each morning, during a session appropriately called Posters and Pastries, I would stand next to our glossy creation (click

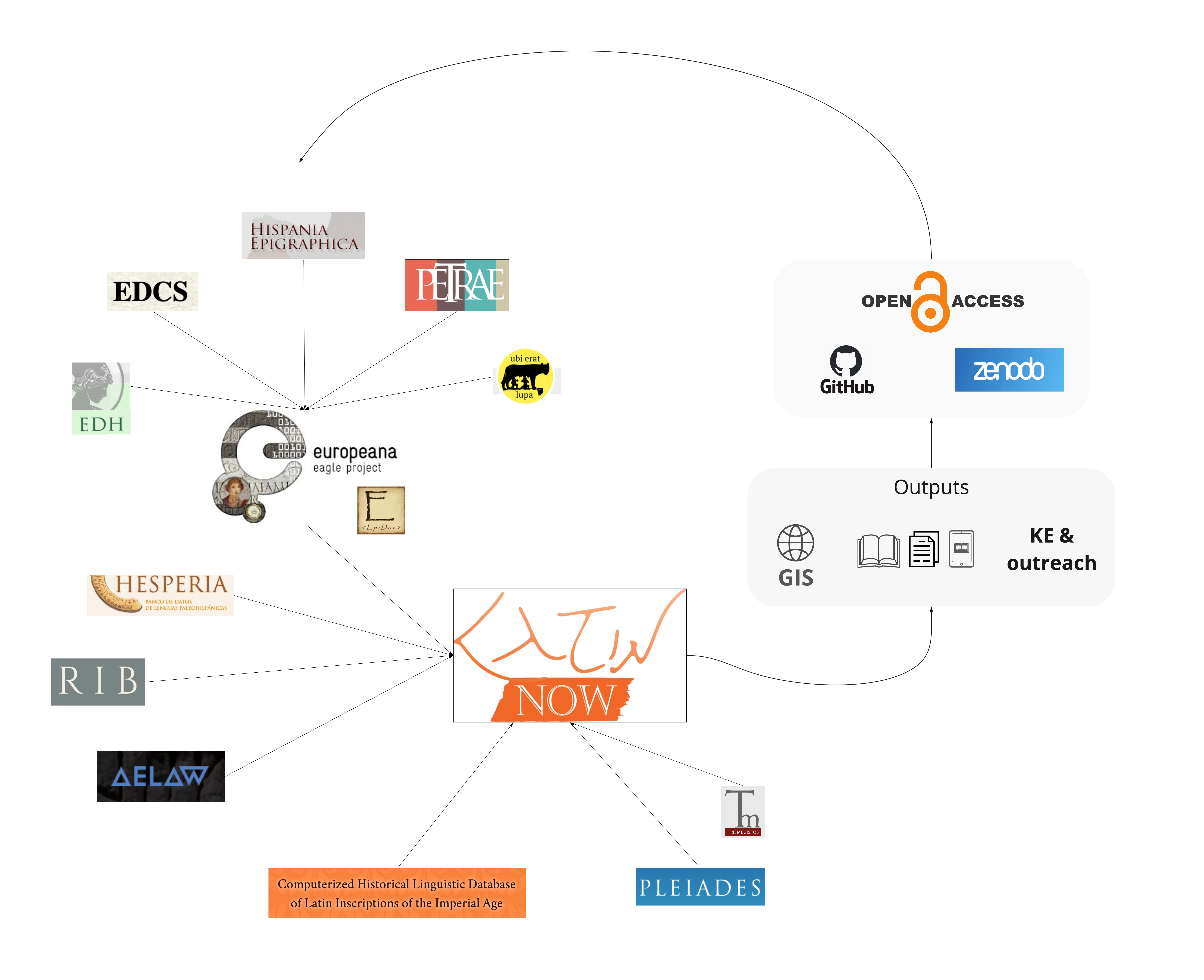

The LatinNow summer started with a training session for the Faculty of Arts at the University of Nottingham and our team on Digital techniques and resources for textual research. Led by Dr Gabriel Bodard (Institute for Classical Studies, London) and me, the DigiText workshop introduced our colleagues to four major digital approaches to humanities research: digital philology, text encoding, linked open data and linguistic annotation. The topics we covered included introduction to online resources, imaging techniques for cultural heritage, methods in digital palaeography, EpiDoc XML markup, LOD annotation, treebanking and translation alignment. While most of our examples were taken from the ancient Mediterranean, the principles and practices applied to all disciplines and cultures represented in the audience – from Scandinavian studies to modern languages translation studies. Our colleagues enjoyed a good amount of practice, starting with marking up modern gravestones in EpiDoc (the more errors and erasures the better), annotating and disambiguating place names in Recogito and aligning translations in Ugarit. Our aim was to showcase these major topics and what progress has been made in digital classics, as well as to highlight the applicability of these approaches and methodologies to virtually all textual research. We had fruitful discussions and quite a few ideas for future collaboration, both national and international – watch this space!

The LatinNow summer started with a training session for the Faculty of Arts at the University of Nottingham and our team on Digital techniques and resources for textual research. Led by Dr Gabriel Bodard (Institute for Classical Studies, London) and me, the DigiText workshop introduced our colleagues to four major digital approaches to humanities research: digital philology, text encoding, linked open data and linguistic annotation. The topics we covered included introduction to online resources, imaging techniques for cultural heritage, methods in digital palaeography, EpiDoc XML markup, LOD annotation, treebanking and translation alignment. While most of our examples were taken from the ancient Mediterranean, the principles and practices applied to all disciplines and cultures represented in the audience – from Scandinavian studies to modern languages translation studies. Our colleagues enjoyed a good amount of practice, starting with marking up modern gravestones in EpiDoc (the more errors and erasures the better), annotating and disambiguating place names in Recogito and aligning translations in Ugarit. Our aim was to showcase these major topics and what progress has been made in digital classics, as well as to highlight the applicability of these approaches and methodologies to virtually all textual research. We had fruitful discussions and quite a few ideas for future collaboration, both national and international – watch this space!

Fieldwork in some challenging conditions in Kent

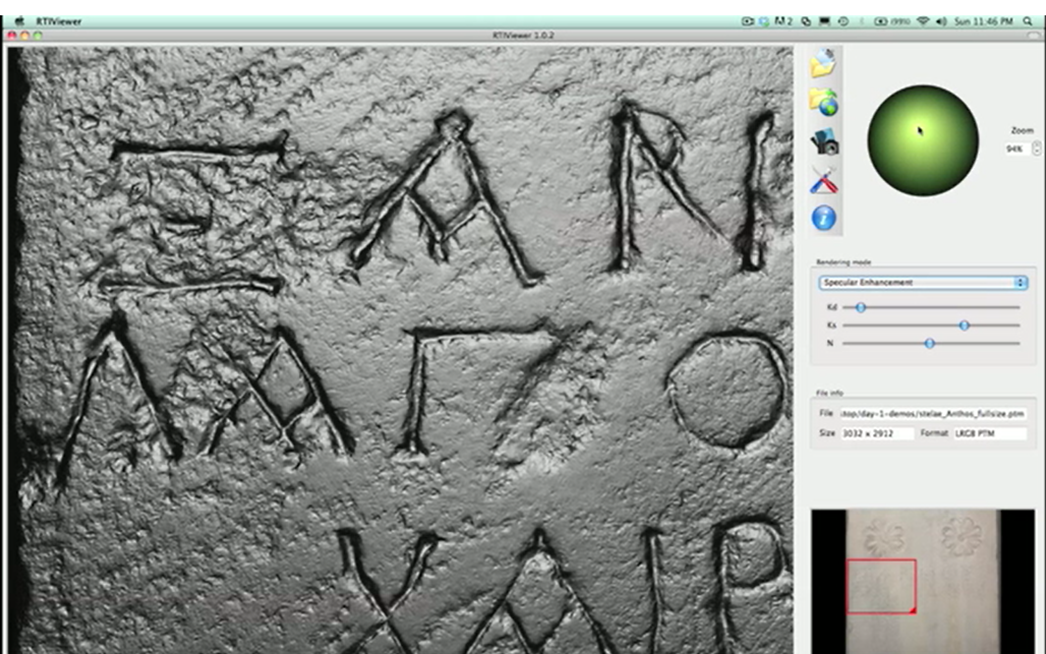

Fieldwork in some challenging conditions in Kent Reflectance Transformation Imagining viewer showing section of Greek text

Reflectance Transformation Imagining viewer showing section of Greek text