By Morgane Andrieu

Dr Morgane Andrieu is an Associate Researcher on the LatinNow Project, leading a sub-project on the graffiti of Lugdunum (ancient Lyon) with the ArAr Laboratory (UMR 5138).

It has now been seven months since the completion of the team phase of the project in the archives of the Lugdunum – Museum and Roman Theaters (Lyon, France). I’ve since moved on to do the more solitary work of analysing the enormous trove of archaeological evidence we discovered in the archives. In these seven months, I first had to adapt to the loneliness caused by losing the team, which was then exacerbated by the COVID-19 confinement situation, leaving the luckiest of us stuck at home. As a consequence, it is not without a little twinge of sorrow that I now look back on the great team I was able to work with last summer in Lyon…

The team stage consisted of opening all the boxes from the museum containing pottery sherds to (re)discover all the graffiti from the Roman city of Lugdunum (ancient Lyon). Not only does the museum have one archive on site, but it also has a second, even larger archive located on the outskirts of the city. In addition to the help I received from the employees of the museum, a total of 37 people, including both volunteers and students, have also contributed at various times to this research project from 2nd May to 30th August 2019. For some of them, it was their first time taking part in an archaeological project and it was clearly an emotionally rewarding and exciting experience. Not only were they granted access to a part of the museum not open to the public, but they were actually able to handle the material. A teary-eyed Gilles summed up the emotion best when he remarked “2000 years of history in my hands!”.

In addition to providing an opportunity to establish direct contact with history and archaeology, it also enabled everyone to become the discoverer of one or several Roman inscriptions, sometimes never seen or long-forgotten amongst other sherds, bones, metal objects, and other items housed in the archives.

The first challenge for me was to train the team in the fundamentals of archaeology. What is an archaeological context? What about a stratigraphic unit? How can you tell the difference between pottery, bone and other materials? How does one distinguish a pot sherd from the sherd of an amphora or a tile? And on the subject of graffiti, What is a graffito and what is not? How should one extract a graffito from its original box and record it? All this information is a lot to take in, especially for those who were discovering archaeology for the first time. To my pleasant surprise, everyone showed real enthusiasm and commitment to rediscovering these inscriptions. Everyone immediately understood their importance of the part they were playing in this international project, namely to help to preserve our cultural heritage and participate in the creation of a previously unpublished corpus that will be shared with the public and the scientific community.

Furthermore, although the inscriptions were often incomplete or short, everyone appreciated the significance they have in contributing to a better understanding of the diffusion of Latin throughout the local culture. As the most common writing surfaces in Roman antiquity – organic material such as papyrus, wax and wooden tablets – have long since disintegrated, funerary inscriptions and graffiti on walls and pottery remain as the primary source of writing of daily life available to us today. The graffiti on pottery we uncovered complement the funerary inscriptions found in Roman cemeteries. They enable us to access the writing of the living in many different contexts (housing, shops, workshops, etc.) instead of focusing only on the funeral inscriptions’ often stereotyped formulas. These graffiti are amongst the few, and perhaps the last testimonies we have to study writing in urban contexts. They’ve proven an invaluable source of insight into the cultural contacts and cohabitation between populations in the region – we found Latin, Greek and Gaulish names! Other pieces of information the team discovered, such as drawings (gladiators, gods, etc), sentences, prices, indications of capacity, of content, of origin, etc. painted a picture of daily life in Lugdunum between the 1rst and 3rd century AD.

Each day we discovered a new batch of graffiti, with names of ancient inhabitants of Lyon, men, women and children, with more or less skillful handwriting. The work was demanding, involving lifting boxes, working in a dusty environment and concentrating for long periods of time on a repetitive task. But the rushes of adrenaline and the excitement of all the new discoveries made it all worthwhile and, along with the good-spirited and enthusiastic team, created a relaxed and happy atmosphere.

This experience was also an opportunity to share our archaeological knowledge with the team. It happened that two of the volunteers, Marie Blot and Romain Deparpe, were also pottery specialists, and they taught others – especially the students – how to produce archaeological drawings of pottery.

However, Marie and Romain were not the only ones who had something to share with the rest of the team. Monique shared her recipe of Gallo-roman bread by Caton, Michelle her recipe of quiche Lorraine (a French specialty) and Valentine shared her uncle’s awesome cake. As you can tell, French people love to find any opportunities to enjoy a good meal together!

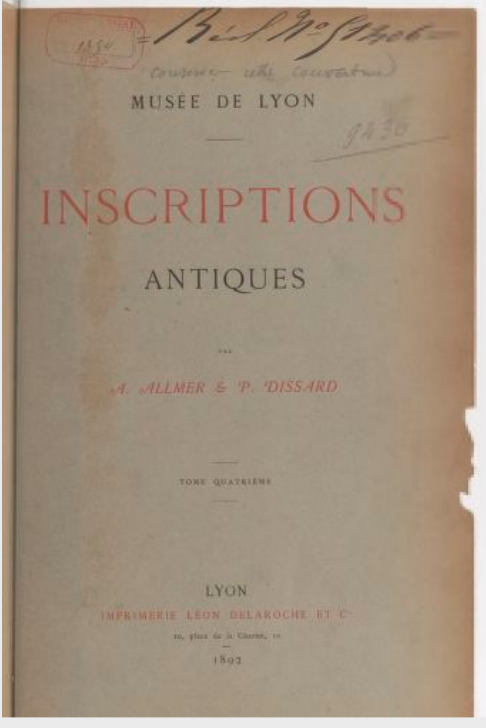

Overall, it was a satisfying experience both intellectually gastronomically (everyone must have gained a kilo or two!). In total, the team ‘unearthed’ more than 900 graffiti. That is 840 new graffiti that can now be added to the 60 graffiti last published by A. Allmer and P. Dissar in 1892, the only publication to pay significant attention to the graffiti corpus of ancient Lyon. But the fact that this 128 year-old publication existed at all was a pleasant surprise, as few French museums have shown an interest in these kinds of objects. Given that these archives and this area of research had remained largely unexplored for over a century meant that, at the start of the project we had little idea of what to expect, so finding such a large number of unpublished graffiti was particularly satisfying and, dare I say, quite a relief!

Since completing the work in the archives last autumn, the work that followed mainly consisted of drawing, photographing and recording all the graffiti found and uploading all the information to a database. As this work takes a huge amount of time, students and volunteers have continued to help. To date, Dominique Durieux has, on her own, drawn more than 495 graffiti. That is a considerable help that she generously brings to the project, even during the C-19 lockdown.

We still have much to learn as we parse, archive and analyze the evidence we’ve uncovered to determine what these fragments of writing, found all across the city, can tell us about the ancient inhabitants of Lyon. Furthermore, despite the enormous effort this summer to sort through the Lugdunum Museum archives, a large number of crates containing archeological material from various excavations around Lyon remains unsearched. To cover the whole city, our research will have to be extended to the other archives of Lyon. Monique L. has encouraged us to ‘Carry on, don’t give up!’ and we will, as long as we can secure funding and enlist great volunteers. To all, a huge ‘Thank you!’. Without your help, I would still be working in the museum’s archive as I write to you… or perhaps, in these peculiar times, not. To my friends, colleagues and readers, I wish you all the best during lockdown. Stay safe!