By Pieter Houten

Starting in Castilian

Last week we started the Touring Exhibition VOCES POPVLI. As always with these big events there are some hiccups to be expected. However, one does not expect people cutting their fingers whilst making bespoke barriers, last minute orders to be covered in oil or delayed flights leading to missing the train and then having to get a taxi for the last stretch of 270 kilometres.

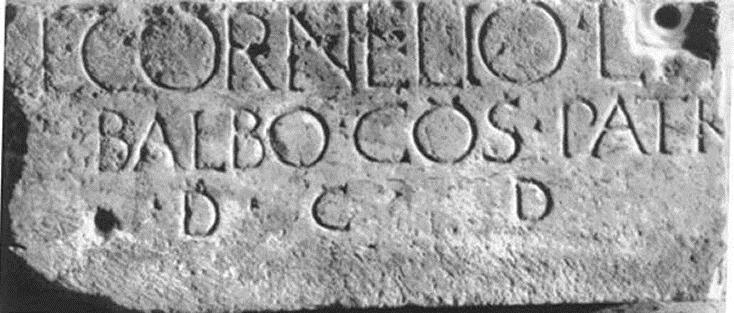

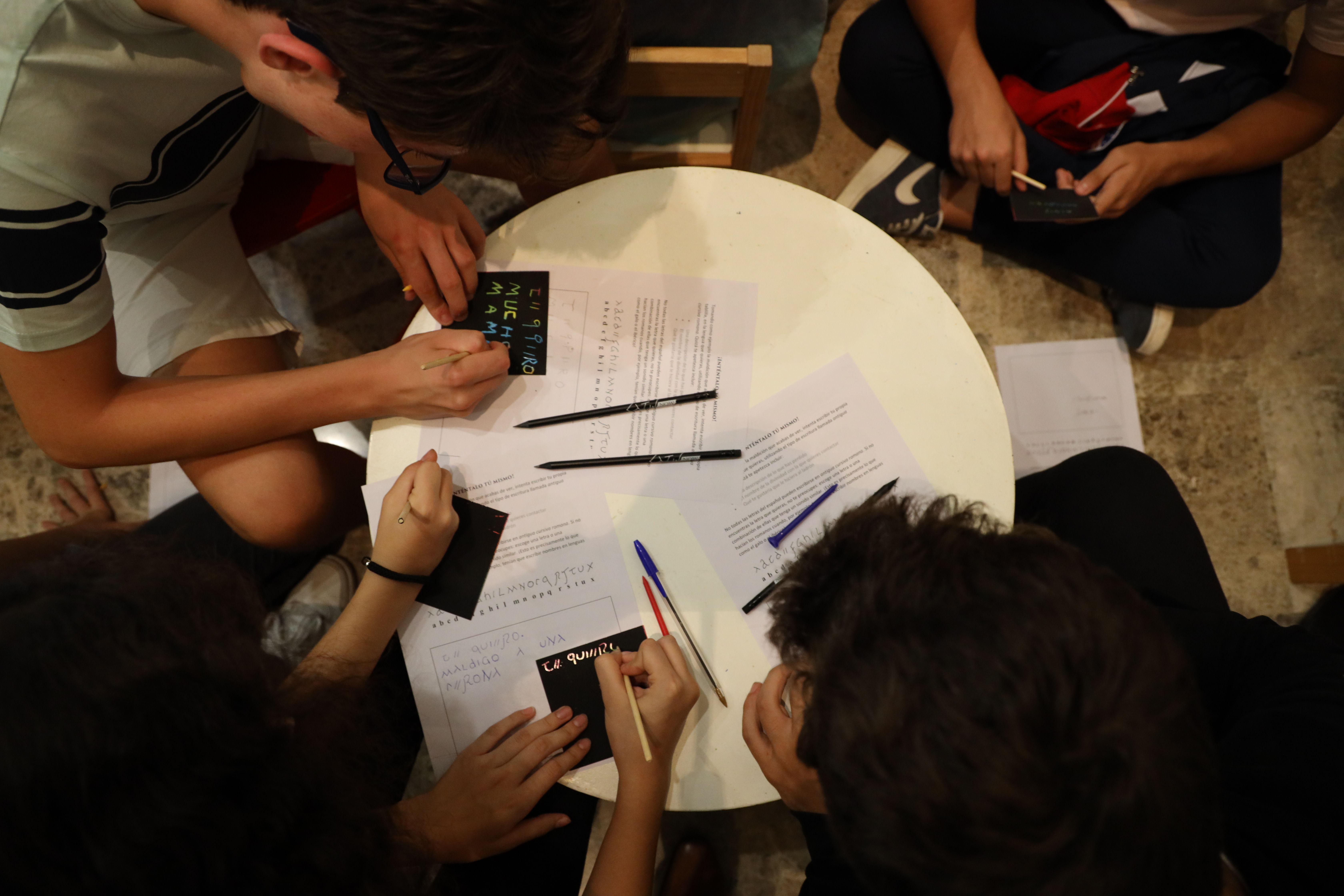

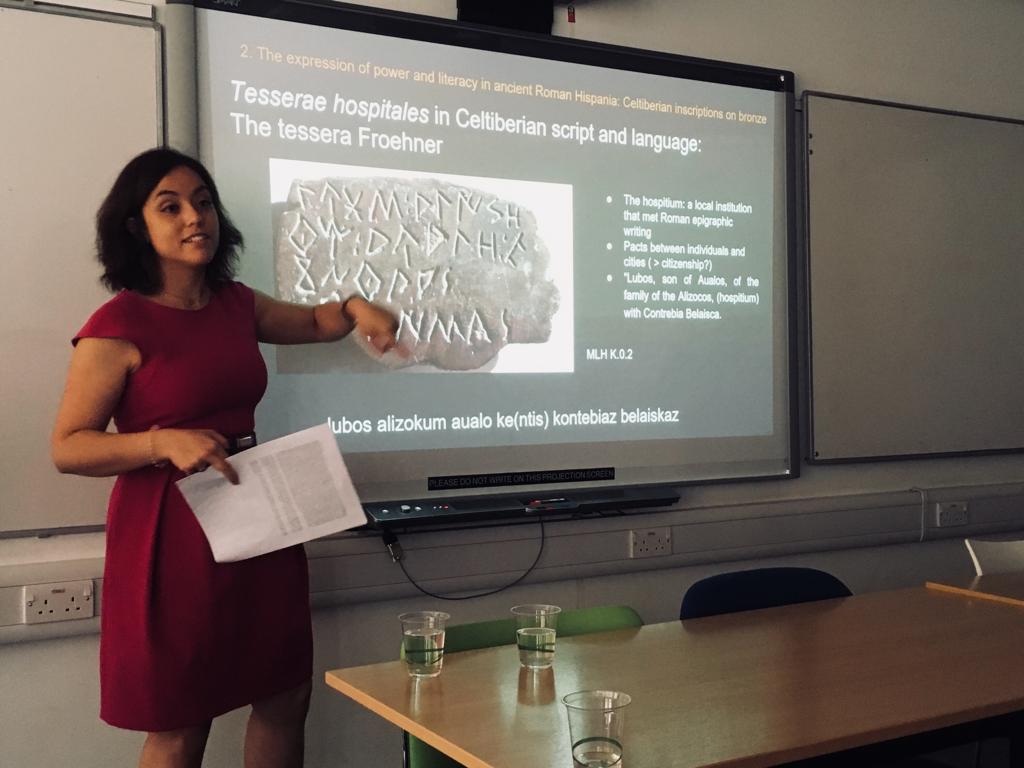

Nonetheless, Monday September 16th 7h30 at the Universidad de Navarra in Pamplona we (Alex Wallis the tour driver from Van Haulin’, María José Estarán and Pieter Houten) were ready for action. María José began with a talk on Latinization. During the talk Alex (the driver) and I were setting up the display. At the sound of applause, we were just finishing the last things. When the students poured out of the adjacent room the display looked almost as planned. Luckily, the students did not realise that some objects were not exactly where they were supposed to be: the eye of the creator (heavily pregnant and confined to the UK) was the only one to spot the switched tesserae, styli and that sort of thing via WhatsApp video. The students just enjoyed learning about Latinization and mostly cursing. It is great how the shrine draws in so many people and actually makes them happy when their curse falls to the right (which we think signifies that it worked). Cursing was so popular that a Professor in Pamplona had to call her students at least three times before they would get to class and still some of them took the curse tablets and styli into class to finish their curses.

After the experience in Pamplona we started the set up early in the Museo de Zaragoza. We knew that setting up took time and we wouldn’t be caught out by the applause again, we thought. Zaragoza had all the bells and whistles: display panels, object table, handling table, cursing and military table and obviously the ‘visitor book’ papyrus-roll. So again, the applause was a small surprise and just as people streamed out of the auditorium, we shoved the last boxes underneath the tables. This time all was where it should be. María José treated the excited audience to a second talk but this time with all the objects at hand. In addition to three large groups of enthusiast adults, we had one school group who particularly enjoyed the cursing activity.

From Castilian to Catalan

As a tour on the effect of Latin on local languages, we had to make the tour multilingual (see Alex Mullen’s previous blog). As a result, we translated all our material from English into the five local languages of our tour. That means Catalan in the autonomous region of Catalunya, where we first halted at the Universitat de Barcelona. As Barcelona is one of these places in the world where it never seems to rain, Noemí Moncunill proposed to set out in the garden of the university. She also invited Professor Velaza to open our exhibition. This time we had everything set up well in time: partly due to our experience at the first two stops and the extra hand given by Victor Sabaté. During the day at Barcelona we had students dropping in to learn more on Latinization. Obviously, we also had passing expert Professors interested in our research and sharing their knowledge on our region. In addition to these students and scholars, we had one very keen local secondary school Latin teacher who actually used our exhibition to teach her four groups about Latinization. Noemí and I enjoyed the eager students reading and translating different objects and through questions learning how Latin spread.

The last stop in Spain was Tarragona. With shame, I have to admit that I never visited the provincial capital of Hispania Citerior before, despite studying Roman urbanism of the peninsula. For those who have never been there, it is more than worth the one-hour train ride from Barcelona. The city is amazing: the amphitheatre overlooking the sea, the still standing city walls and the dots of Roman ruins all over the city make it a joy for anyone who loves Roman history. Certainly, one has to visit the Museu Nacional de Arqueològic de Tarragona (MNAT), so did we with our tour. Unfortunately, for us the MNAT in the centre was under reconstruction, luckily they have a good temporary location with the highlights of their collection. Here we had again four school groups visiting as part of their Latin curriculum. Noemí gave an introduction into our project and explained Latinization using our display. Thereafter the students were sent on a quest looking for objects related to all six social factors in the museum.

It is great that the MNAT incorporated our display themes into a bespoke trail around their collection. After students located all six objects related to the social factors, they returned for the cursing workshop. One of the Tarraconese teachers shouted during the explanation of the “Curse like a Roman” workshop: “It is forbidden to curse the teacher!” The Tarraconese students are a friendly lot, they wrote curses upon we can hopefully all agree…

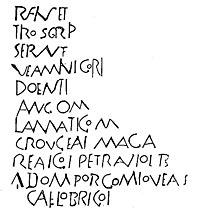

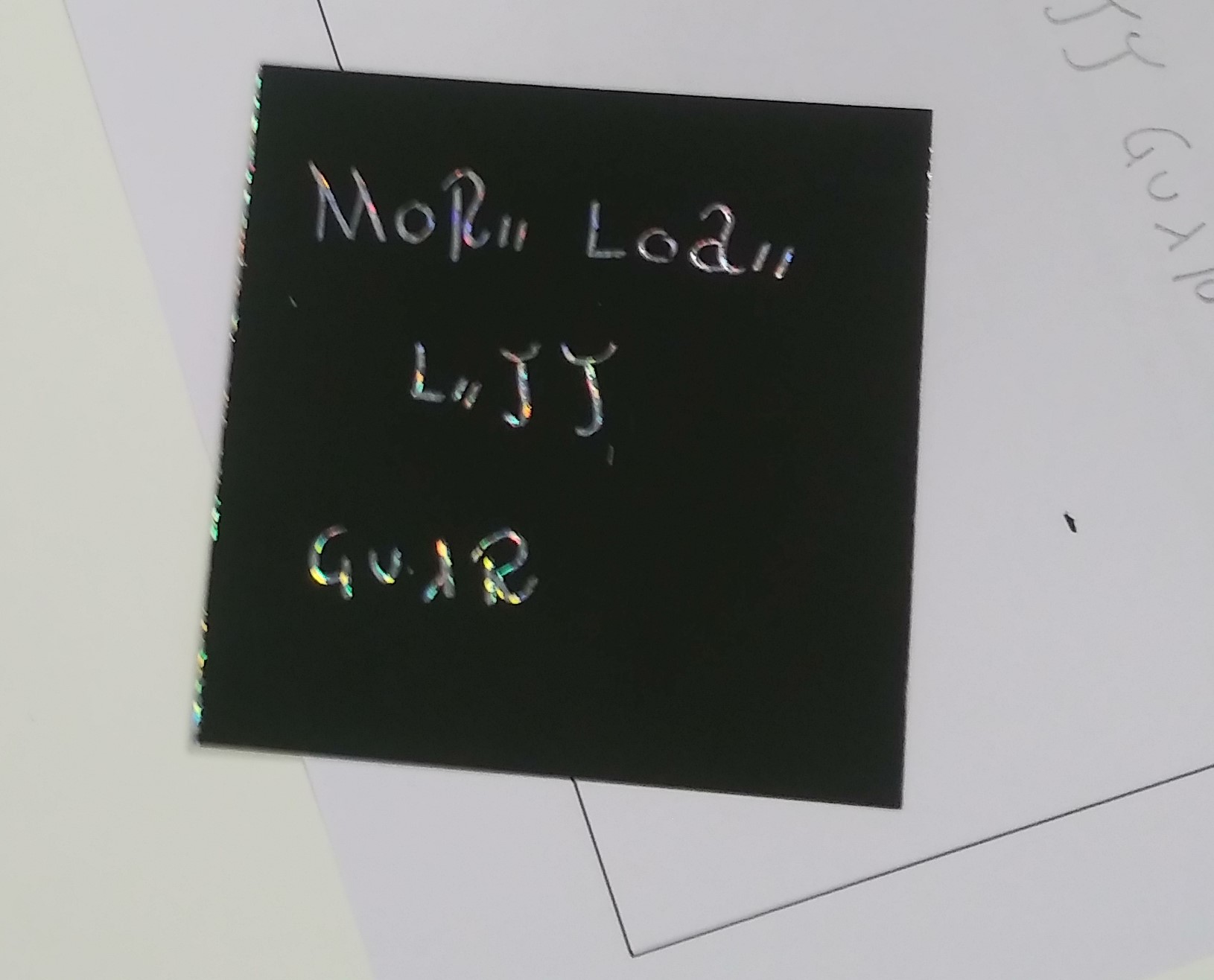

Since the Romans did not have all letters we now use, we have to be creative when writing using Old Roman Cursive, we can use letters that look similar or write it phonetically. This is an Catalan-speaking student’s rendition of English Make love, less war into ORC.

After the week in Spain it was time for our driver to continue to France and visit Millau, Nîmes and Vienne with Morgane Andrieu and Jane Masséglia. I had the joy to spend a few more days in Tarragona as I had a conference later that week in Pamplona. Luck had it that the feast of Santa Tecla was during my stay in Tarragona, the fun must go on!

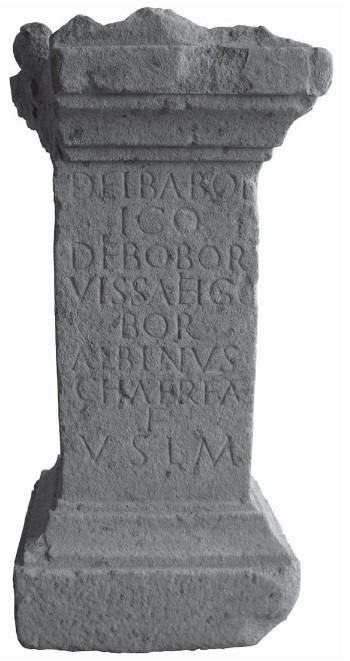

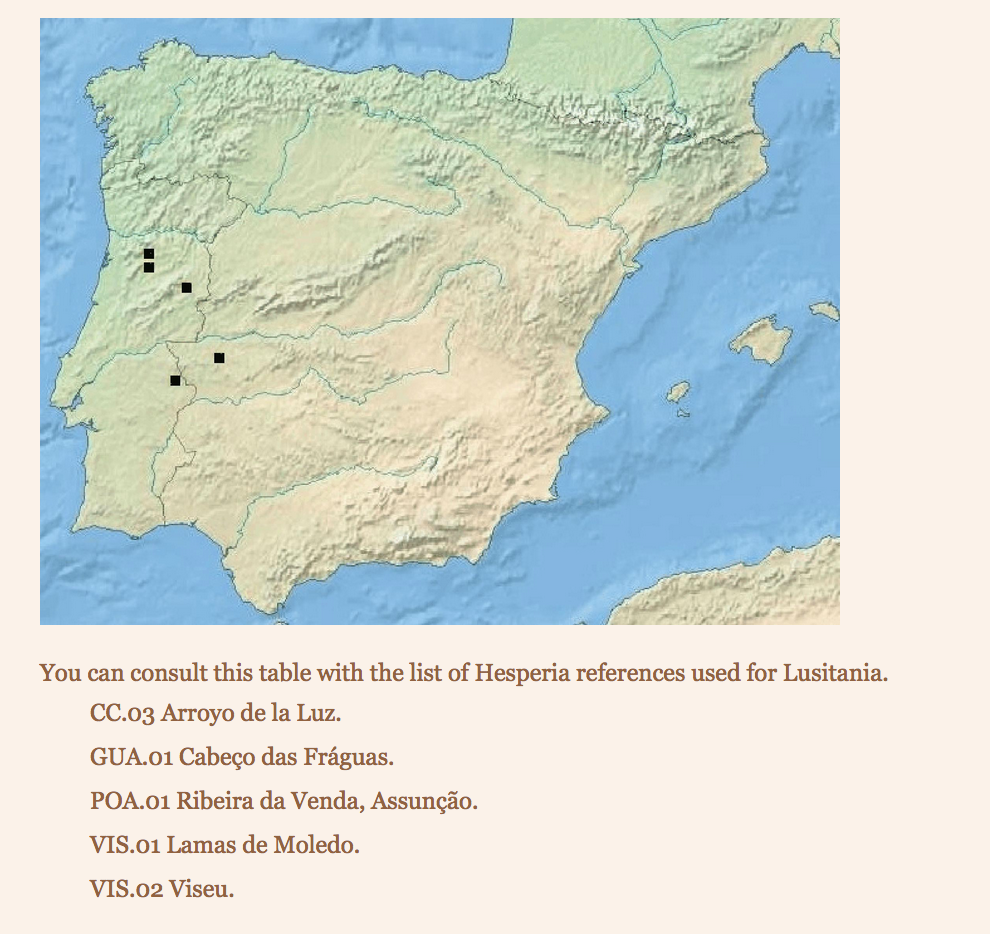

Fig. 2. Map of the Lusitanian inscriptions according to Hesperia Database.

Fig. 2. Map of the Lusitanian inscriptions according to Hesperia Database.