By Janie Masséglia

The second half of June proved to be a busy one for the LatinNow Project with more than 200 visitors and students taking part in our new workshops and activities in less than a fortnight.

Since we put together our LatinNow Outreach Events Menu 2018, two of our most popular activities have been about Old Roman Cursive and writing curse tablets.

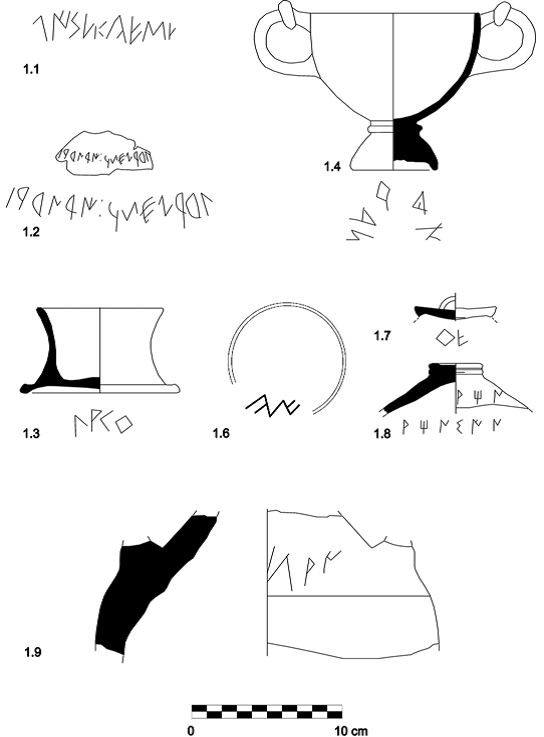

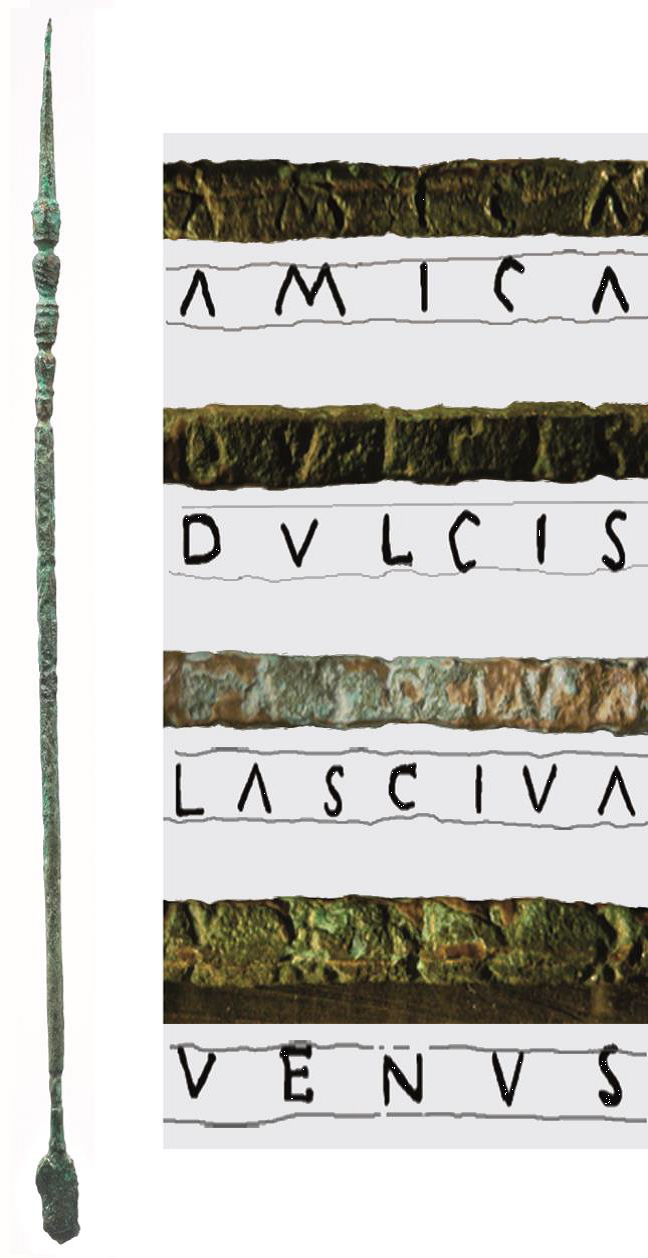

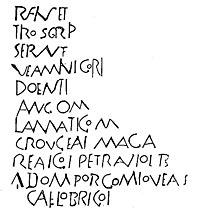

Our trusty cardboard shrine to Sulis accompanied me to the Family Discovery Day at the University of Nottingham, to two in-school sessions at the Iris Classics Centre at the Cheney School in Oxford, and then again – this time with Alex making a trio – to the History and Archaeology Festival at Nottingham’s Lakeside Arts. For this activity, as well as having the chance to handle replica writing instruments of various kinds, people were encouraged to decipher mock lead-tablets describing the loss or theft of various items, before writing their own and dedicating it to Sulis. I had been initially disappointed to discover that the small squares of scratch paper I hoped would replicate child-friendly lead plaques were not available in silver, but only in rainbow effect. Sometimes the quest for absolute authenticity doesn’t lead to the best visitor experience – our visitors (especially the younger ones) have been drawn to the bright colours and have loved experimenting with Old Roman Cursive when it gives such an eye-catching result. We’ve embraced it and are determined from now on to ‘be more unicorn’.

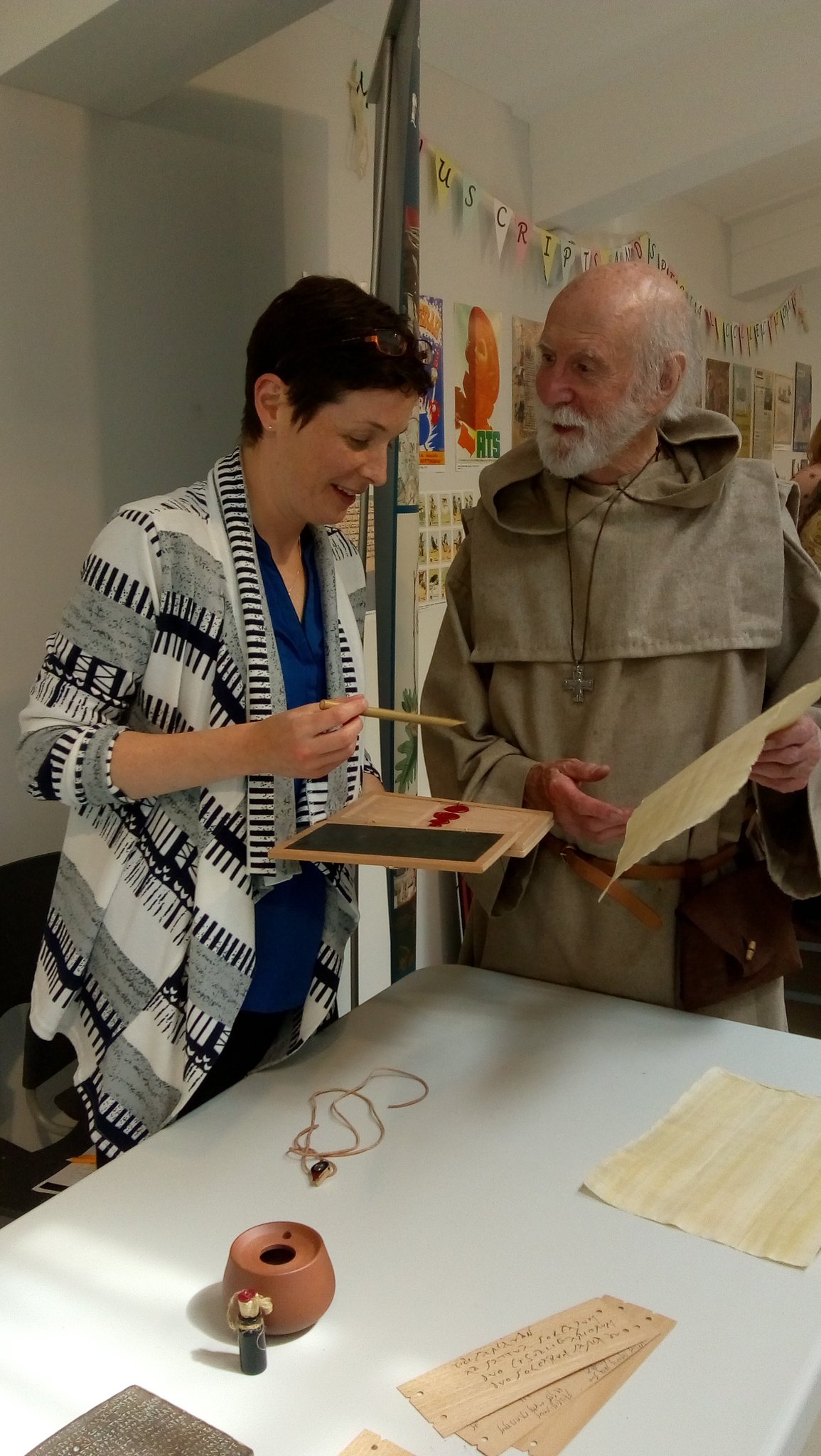

One of the unexpected highlights of the History and Archaeology Festival was the chance to meet re-enactors of various periods. We talked about writing techniques with a medieval Benedictine, and even faced an invasion of Iron Age Celts who came up to tell us they didn’t like the Romans much, and they had no intention of learning about Latin! Once Alex was able to reassure them we loved Celtic too, and even showed them some Celtic words hidden in a Latin contract we had on our stall, we managed to broker a peace. Now that’s community engagement.

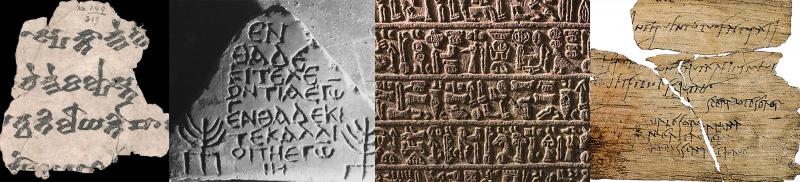

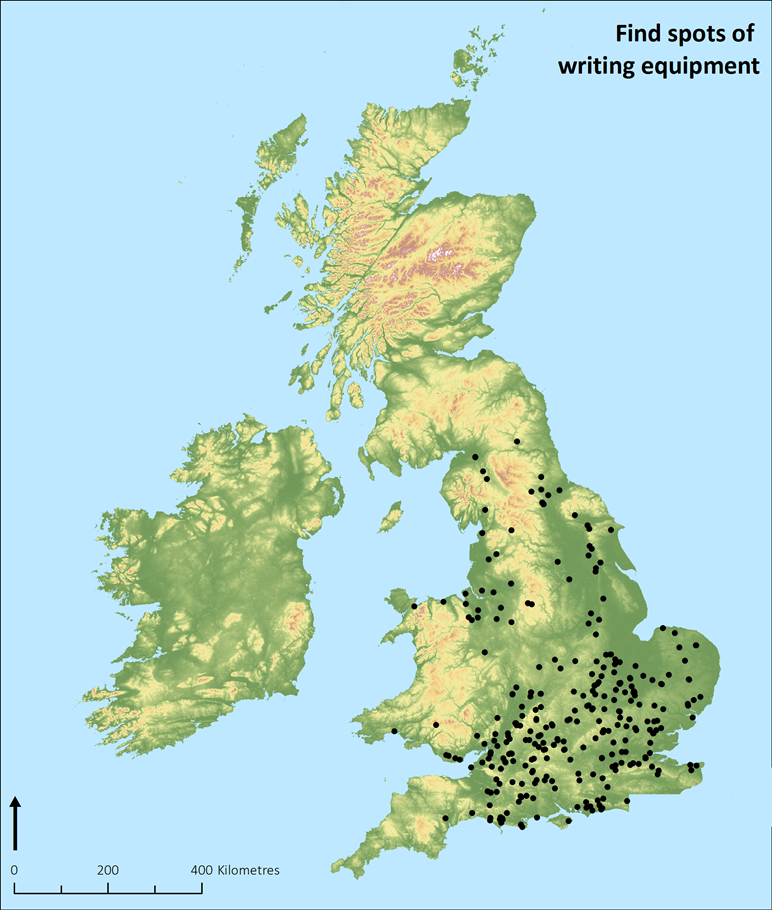

Our other popular session has been our military ‘codebreaking’ for Primary school pupils, an activity that Alex, Joshua Ward-Penny and I successfully road-tested on 250 children and their parents for the IntoUniversity programme last March. This session, focussing on the different languages spoken in the empire and how the Roman army sent its messages, always ends with a race to translate a secret message and save a Roman legion from an attack from marauding Britons. Last week, the pupils of St Ebbe’s Primary did a fantastic job, and a little girl named Mahisa stormed to victory several minutes before her classmates. It’s a pattern that we’ve started to notice, that children who speak more than one language are especially adept at codebreaking cursive, and it’s been great to talk about multilingualism with young people who really understand what we mean.