By Scott Vanderbilt

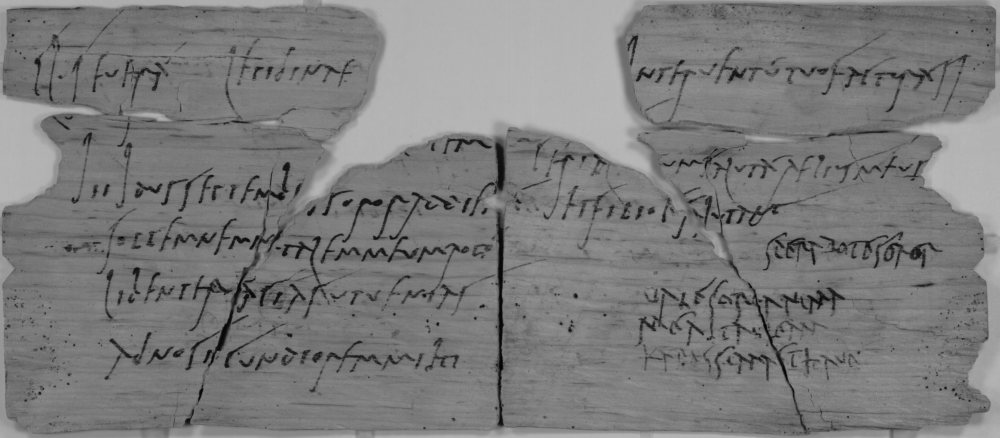

I’ve been asked to mark the anniversary of one of the more famous dates in Romano-British history, namely that of the birthday of Claudia Severa, born on the 11th of September sometime in the late first century CE. Many have commented on the significance of the party invitation letter to her dear friend Sulpicia Lepidina, wife of the fort commander at Vindolanda (Tab.Vindol. 291), and I certainly have nothing original to add that hasn’t been said before. And, yet, having spent more than my fair share of time with the writing tablets from Vindolanda and the inscribed texts of Britannia in general, I never cease to be amazed by the countless examples of the reminders of how the authors of these texts, notwithstanding the nearly two millennia that separate us, are in many important respects not very different from us at all.

One thing that Severa and I share is a close personal bond to Vindolanda and its inhabitants. Though she herself resided elsewhere (Briga?), it’s fairly certain she was at least an occasional visitor. And if the roads are as bad as Octavius would have us believe (dum uiae male sunt, Tab.Vindol. 343.21), perhaps her journey in inclement weather was no less time-consuming than my own 10-hour transatlantic flight from Los Angeles to Heathrow and a six-hour drive up the A1. (Severa no doubt counted herself lucky that she wasn’t born in February, or the unforgiving Northumberland winter might never have allowed her any guests at her birthday parties.)

I first chanced upon Vindolanda in the summer of 2010, when I conscripted my three children–the youngest of whom was about to ship out to university for the first time and leave me an empty-nester–into a valedictory holiday walking the entire length of the Hadrian’s Wall Path, one of the glories of the English national trail system. On the third day, I managed to cajole the kids into deviating from the path for a short jolly down to Vindolanda (“not another Roman fort”, the middle one sighed with contempt, coupled with the obligatory dramatic eye-roll that she had mastered at an annoyingly young age). My guidebook had tantalized me with the prospect of being able to observe in-progress archaeological excavations.

An hour later, we were standing at the edge of the barrier and a very friendly excavator stepped away from the trench, brought over a finds tray for us to examine, and cheerfully answered our inane questions. As I recall, there really wasn’t much in it other than some grotty animal bones, heavily corroded nails, and a few desultory pieces of worn terra sigillata. But it might just as well have been the treasure of Tutankhamen, as far as I was concerned. And when I found out he was a volunteer, and that anyone could participate merely by signing up the previous fall, I felt as though I had been struck on the road to Damascus. Of course, I may be over-romanticizing it a bit. But there is no doubt that what transpired that day set in motion a whole series of events, not least of which was the decision to create RIB Online, nine successive annual trips to Vindolanda as an excavator, and serendipitously, the invitation to join the LatinNow team.

Excavating at Vindolanda is a fantastic experience and a particular thrill for someone like me who has a special interest in the fruits of these excavations. Most years, it probably doesn’t differ tremendously from a lot of Roman military sites in Britain, apart from the extraordinary density of finds. But in the years when the Scheduled Monument Consent calls for it, certain areas are opened up which allow for exploration of the earlier fort phases and their accompanying extramural settlements that fall below the present water table. At this depth are the oxygen-deprived anaerobic layers that completely arrest any degradation of organic remains and allow for the preservation of artefacts that would have disappeared under any other conditions long ago, including the precious stylus and ink writing tablets.

2019 was one such year, and I had the good fortune to be assigned to one of these trenches during my fortnight session. Employing a time-tested protocol worked out over decades by Vindolanda’s archaeologists, these organic layers are gently spaded in more-or-less 20 cm cubes by a single digger, much as a peat cutter would, and lifted out of the trench and distributed among several diggers kneeling over barrows, who then gingerly sift through the cubes carefully looking for the tablets and anything else that happens to pop out of the black, pungently aromatic organic material. Only bare hands are allowed, as gloves would deny the sifter the tactile sensation required to separate the wafer-thin, highly fragile tablets from the rest of the laminate in which they are found.

While I enjoyed my shifts in the trench doing the spade work, it was incredibly nerve-wracking. The prospect of slicing through a tablet that I knew years later I would see again in a high-resolution infrared photograph in a future volume of Tabulae Vindolandenses as a collection of conjoined fragments, knowing that I was the one who put them asunder, would be almost too much to bear. Thankfully, that fear was not realized, but Dr. Andrew Birley, director of excavations, did spot a small fragment of an ink writing tablet in one of my spaded blocks, perhaps the size of a large postage stamp. It clearly bore traces of ink, but nothing was immediately legible on it. Like all such finds, it was quickly placed in a plastic Tupperware container filled with water from the trench and whisked away to the laboratory for conservation. I hope to see it again, but I doubt I shall recognize it. However, simply knowing something I’ve personally extracted from the ground will end up as one of the Vindolanda Tablets is satisfaction enough.

Sadly, my trip this year for what would have been my tenth excavation season was scuppered by the present pandemic. Of course, as great a pity that is, it certainly pales into insignificance when one considers all the suffering that the world has undergone this year. But I am exceedingly grateful for all that my past journeys have brought me, not the least of which is the many friendships I have been fortunate enough to have developed, both with the tight-knit group of excavators with whom I dig every year, and the members of the LatinNow team.

Which is something else I share with Claudia Severa–the yearning for the company of good friends whom I don’t see nearly as often as I would like, kept apart by impassable roads (or an ocean). Until then, I hold Vindolanda and my friends close to my heart, and anxiously await a return as soon as possible.