By Pieter Houten

As a classicist I seem to have this nerd’s-eye view on all things related to our field. Yes, I will write about the Netflix-series ‘Die Barbaren’. But, no, I will not write about how it is not historically accurate enough. We can put salt on all snails, as we say in Dutch. They didn’t need to make the mistakes of having the Germanic warriors ride horses with stirrups (was it for insurance reasons?) and having a tiger skin, rather than a lion, in the military outfit of the eagle-bearer. Yes some of us notice these things, but we also realise it is a series created for entertainment. For me the interesting choices they have made about language have made the series even more entertaining and to explain why I will give you a peak into my nerd brain.

The series starts with the Germanic people speaking modern German, no surprise there as it is a German series. But then the eagle-bearer and a small troop of Roman horsemen led by the centurion Metellus enter. And this is when the fun starts. Metellus rides to the Cherusci for an announcement: in Latin. That is when I realised that the modern German is supposed to represent the Germanic language of the Cherusci. We could start a debate about how far off modern German is from the language spoken 2000 years earlier. However, unlike Latin, the Germanic languages of the time have not been preserved beyond names. Unfortunately, the Germanic Batavian commanders at Vindolanda, for example, learned Latin so well that there is no obvious evidence, apart from the odd Germanic name, of Germanic in the reams of Latin they left behind. Admittedly, some bright people could have been hired to reconstruct a variety of Proto-Germanic from known early Germanic languages such as Gothic. However, that would open up new debates: for example, if you start going down that lane you should perhaps also consider the possible dialectal differences between the Germanic of the Cherusci and Bructeri. So we can easily forgive the use of Modern German.

The choice to have them speak different languages is a nice touch allowing viewers to understand a bit more of the difficulty of interactions in a new province. Metellus announces in Latin that there is a new legatus Augusti for Germania, the one and only Publius Quinctilius Varus. However, Metellus quickly realises that the Cherusci did not understand a word of the announcement. That is also when we get the next surprise: Segestes steps up as interpreter. Apparently, this Cheruscan elite member has learned Latin. Bilingualism in the northwest, in action – exactly the kind of thing we study in LatinNow!

Interestingly, Segestes’ role as the conniving-double-playing interpreter fits the classical idea of multilingual people that we sometimes see in elite literature. In antiquity, multilingual people were not always received with much laus and gloria. In Plautus’ play, Poenulus, the Carthaginian Hanno is portrayed as speaking all languages (Poen 112). When he switches from Punic to Latin, Milphio calls him a double-tongued snake (Poen 1029-34). Moreover, Livy recounts that the Carthaginians, the famous rivals of Rome, could not be trusted for their multilingual capabilities, they could write in Latin to mislead the Romans (Liv. 27.28.4). Back in Die Barbaren we also see that Roman officer Arminius uses his bilingualism to plot and scheme with the Germanic peoples. That Arminius was bilingual is also noted by Tacitus who records that Arminius spoke his Germanic language with Latin interference (Tac. Ann II.10). I will not go into this any further as that might entail spoilers for the next season…

Similarly in this season, we learn about Arminius’ bilingual background when he contacts the prefect Talio of the Germanic auxilia. We have to note here that the auxilia in the Roman army were drafted from the provinces. As Arminius leaves, Talio makes a joke in German. As it was about the Roman Empire and Arminius overheard it, he responds in German. Again the bilingual speaker is shown as something to fear, and unfortunate Talio is whipped for his insubordination. The ending of the first episode reinforces Arminius’ bilingualism with the code-switching cliff-hanger: “Salve Vater” “Greetings, Father” (Latin, German).

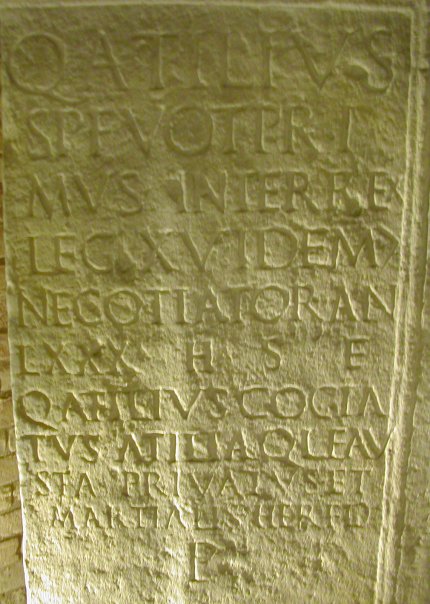

When Arminius and Thusnelda visit the legionary camp Arminius’ forked tongue is clear. He is not literally translating what is being said. But that might have been a wise choice. Thusnelda is not inclined to be friendly to the Romans and insults them in Germanic. However, this is a dangerous game, as there is an interpreter on the Roman side: Pelagios. We know from inscriptions the Roman army had interpreters. In the Germanic area of the Marcomanni there is an inscription from Boldog (Senec, Slovakia) mentioning the centurion Atilius who also served as inter(p)rex.

Looking for these linguistic references in the series is quite fun. They are a nice touch for a series in the sword-and-sandal genre which focuses on the warlike interactions. The series could even have stretched the story to show more aspects of the Roman and Germanic interactions – for example the development of cities and trade in the new province and how interpreters like Segestes might have fitted into this too. The interactions in the new province were not only of war-like nature, it was all a bit more complex. Die Barbaren is a great watch though and hunting down these linguistic features is a fun activity diverting my mind, at least, from the problems of our own time.