By Noemí Moncunill Martí

One bit of evidence that in the late republic the south of the Iberian Peninsula was strongly Romanized is that some relevant figures of this period come from this region. This is the case of the wealthy family of the Balbii from Gades, in modern Andalusia.

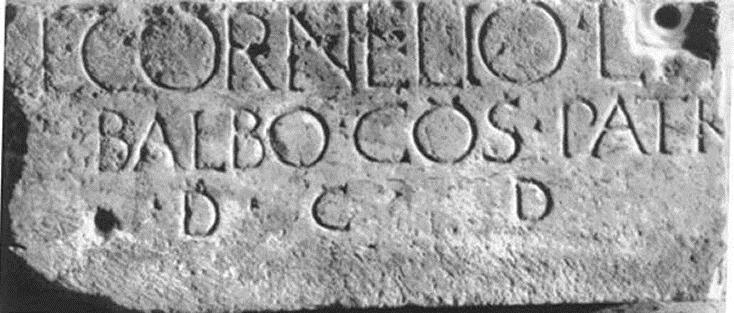

Inscription from Capua mentioning Lucius Cornelius Balbus Maior (CIL X 3854; ILS 888)

One of them, Lucius Cornelius Balbus Maior, played a crucial role in the politics of the Roman republic. He was granted Roman citizenship by Pompey the Great as a reward for his collaboration in the Sertorian War, in Hispania. Once a Roman citizen, he also managed to meet Julius Caesar, with whom he would become a close friend, as well as counsellor, secretary and, thanks to his great fortune, even the financier. The Gaditanus became so well-connected and influential that he has been considered as the principal intermediary between the two most prominent politicians of that time, Caesar and Pompey, and one of the shadowy ideologists of the first triumvirate, to the extent that some voices have considered his activity as one of the main causes that led to the irreversible erosion and fall of the old republican system.

Balbus’s biography shows a man of extraordinary political agility, able to remain in the political forefront without ever being damaged, in spite of the great instability dominating the social and political scene. He was a man who, despite being directly involved in the first triumvirate, was also involved in the second triumvirate, during which he reached the peak of his political career: in 40 BC he was elected consul, becoming the first non-Italian to hold the highest office.

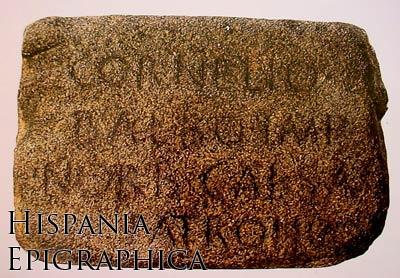

Honorific inscription to Lucius Cornelius Balbus Minor found in Cáceres, Extremadura (AE 1962, 71).

One of Balbus’ nephews, Lucius Cornelius Balbus Minor, followed in the steps of his uncle attaining notorious political and military success. In 19 BC, he became the first non-Italian to celebrate a triumph in Rome. He is also well known for promoting an urban renovation of his native Gades and for funding some important buildings in Rome, including a theatre.

Model of Rome showing the Theatre of Marcellus in the foreground and the Theatre of Balbus in the background (Wikimedia Commons)

Further reading:

Espluga, X. and Moncunill, N. 2013. «Introduction to Pro Balbo», in Cicero, Discursos XVI, Fundació Bernat Metge, Barcelona.

Pina, F. 2011. «Los Cornelio Balbo: clientes en Roma, patronos en Gades», in A. Sartori and A. Valvo (coord.), Identità e autonomie nel mondo romano occidentale: Iberia-Italia Italia-Iberia. III Convegno Internazionale di Epigrafia e Storia Antica (Epigrafia e Antichità, 29), Faenza, 335-353.

Rodríguez Neila, J. F. 1996. Confidentes de César. Los Balbos de Cádiz, Madrid, Sílex ediciones.