By Francesca Cotugno

Obsecro, domne, nonne tua interest aliquem defigere? This was probably a sentence which might have been said multiple times, all around the Roman Empire. In order to curse someone in the Roman Empire a curse table was probably a quick and readily available option.

Curse tablets are inscribed pieces of metal, usually in the form of small, thin sheets, intended to influence, by supernatural means, the actions or welfare of persons or animals against their will (Jordan 1985: 151). This might mean subjecting a thief to a nasty fate or making someone fall in love with you. As Roger Tomlin put it in his presentation of the Bath curse tablets they were the “loser’s last resort” (Tomlin 1988: 60).

But not all the surviving curse tablets are similar and this is one of the things that intrigues the LatinNow team. We are trying to understand these documents, which sometimes contain the innermost desires of people: how are they differently distributed around the provinces and how did they adapt the feature of cursing someone with a lead tablet to their own culture and language, often creating something new and unique?

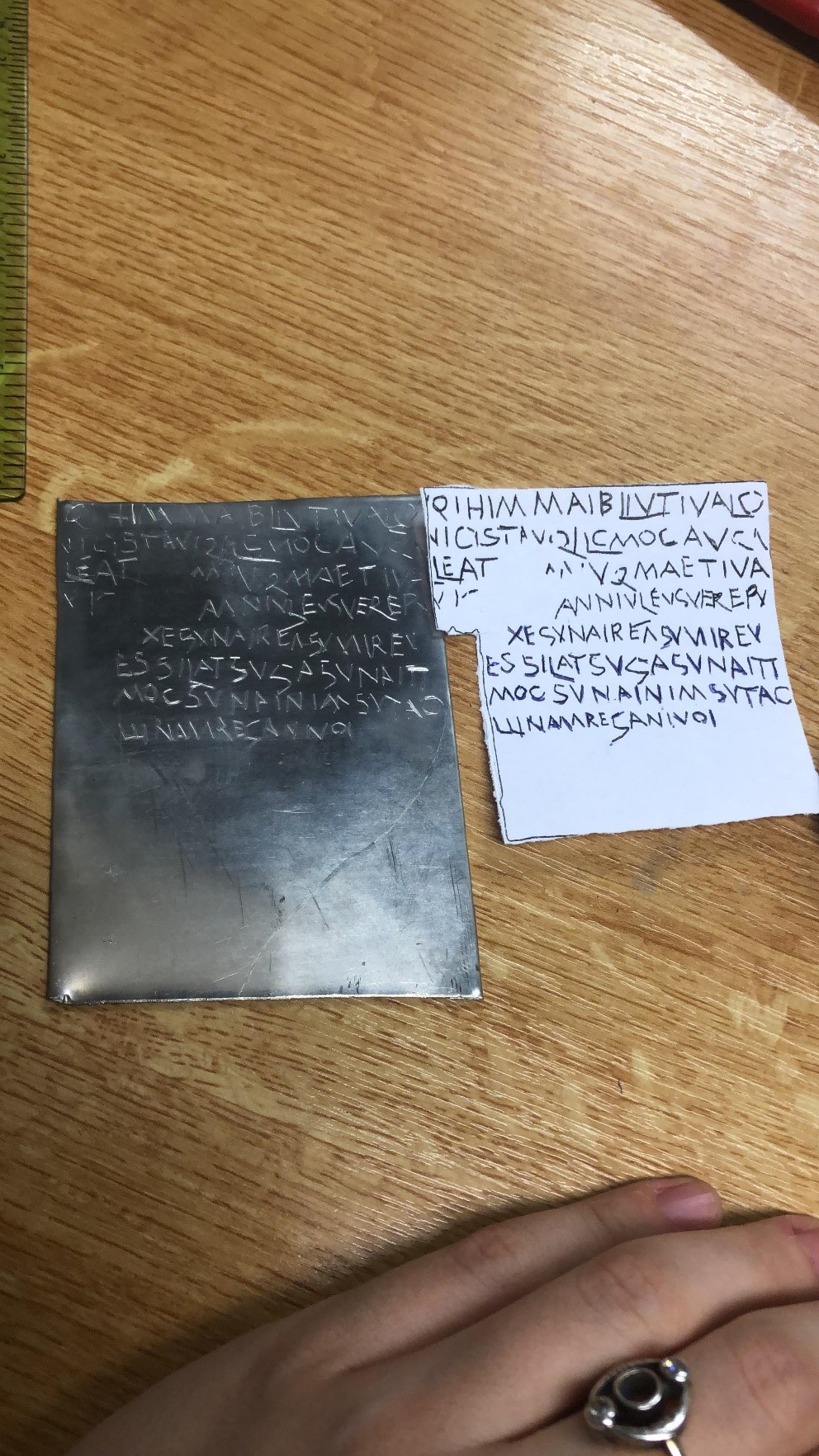

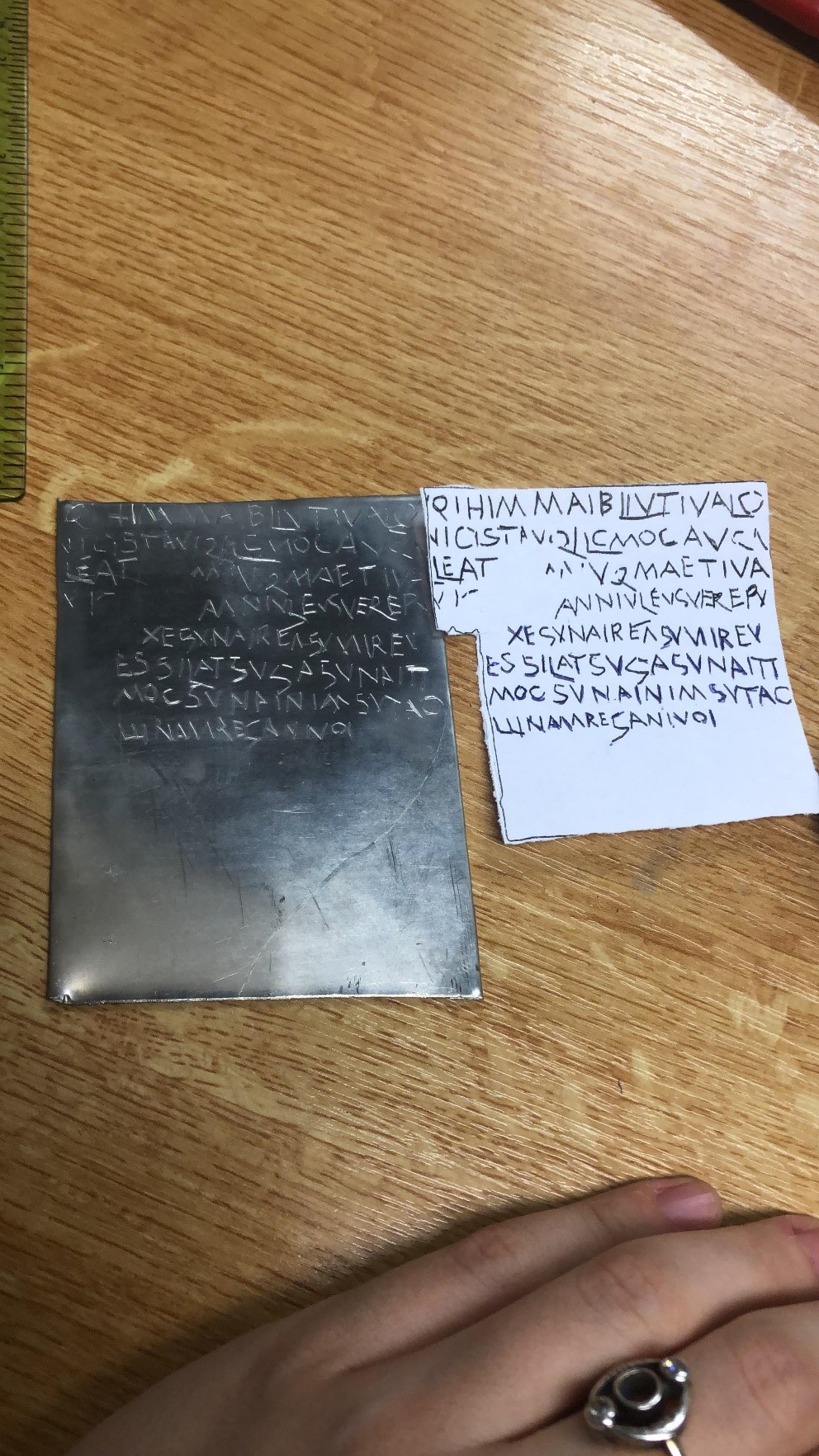

These curses are usually called lead tablets but, actually, this is not the only metal that was used for this purpose, as we also find other soft metals like pewter and tin. In general, the tablets are rectangular sheets which were 6-12cm long and 4-8cm wide when unrolled in order to provide a writing surface which was inscribed with a sharp point like a stylus. As you can see from the picture (figure 1), the LatinNow team is producing replicas of these tablets for the forthcoming Touring Exhibition in September and October 2019 (https://latinnow.eu/touring-exhibition/).

Figure 1. The Vilbia curse tablet replica in progress.

Curse tablets have been found in different provinces of the Roman Empire, but they belong to different periods and to different linguistic areas and backgrounds. Whereas the Romans spread the habit of written curses, indigenous communities coloured them with their own distinctive features, which may reflect, in some cases, ancient oral practices. This is perhaps evident in the case of the curse tablets from Roman Britain, where the writers adopted the practice of the curses with special concern for theft. In Britain, the richest site for curse tablets is Bath, ancient Aquae Sulis, where they were deposited in the hot spring between the second and fourth centuries AD. Here the writers used a lot of formulaic language, like the form si mulier, si baro (e.g. Tab. Sulis 44), which appears to indicate Germanic influence.

In places such as Germania Superior, among others, theft, as far as we can tell, was not such a major topic for cursing someone. In Mainz, people were cursed in the first and second century AD at the sanctuary of Isis and Magna Mater because the writer was holding a personal grudge and not necessarily because he or she was asking revenge for a stolen good. DTM 1 is one of the few curses in which the curser is asking for a punishment against a thief (in this case, a certain Gemella allegedly stole a fibula). The majority of curses here are invocations expressed in a quite plain language which did not have to be learnt by heart or copied from magic books, but they also include some more formal terminology, and stylistic elements of artificial or popular rhetoric.

Taking into account two different curses, one from Bath, and another one from Mainz, it is possible to note some similarities and divergences.

Tab. Sulis 4 is also known as the theft of Vilbiam. Whether this curse was about a kidnap or a robbery has been discussed by Paul Russell (2006).

| Latin – transposed version |

Translation |

QV[..] MIHI VILBIAM IN[..-]

OLAVIT SIC LIQVAT COM[..] AQVA

ELL[…] M[. 2-3.]TA QVI EAM [……-]

AVIT SI VELVINNA EXS

VPEREVS VERIANVS SE

VERINVS AGVSTALIS COM

ITIANVS CATVS MINIANVS

GERMANILL[..] IOVINA |

May he who has stolen Vilbia become as liquid as water ..who has stolen it (or her) Velvinna, Exsupereus, Verianus, Severinus, Augustalis, Comitianus, Minianus, Catus, Germanilla, Jovina.

|

Why is Vilbia not a woman? It is difficult to understand this word as a personal name: firstly, it is not attested elsewhere, and no other British curse tablet is prompted by the theft of a woman. We have curses prompted, for example, by the theft of silver coins (Tab. Sulis 4) or for the theft of a pan (Tab. Sulis 60). I agree with Paul Russell that it is not really likely that it refers to a woman. He suggests that the form may be related to Middle Welsh gwlf, and may refer to some sort of pointed object. Tomlin suggested that Vilbia was perhaps a form of fibula (“a brooch”). In the curse tablets from Bath we have also other curses concerning this kind of item, such as Tab. Sul. 15 made for the theft of a bracelet.

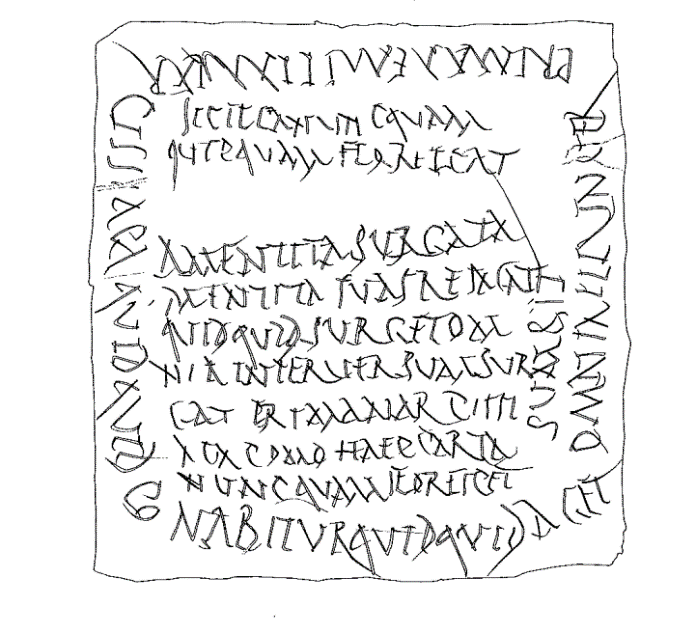

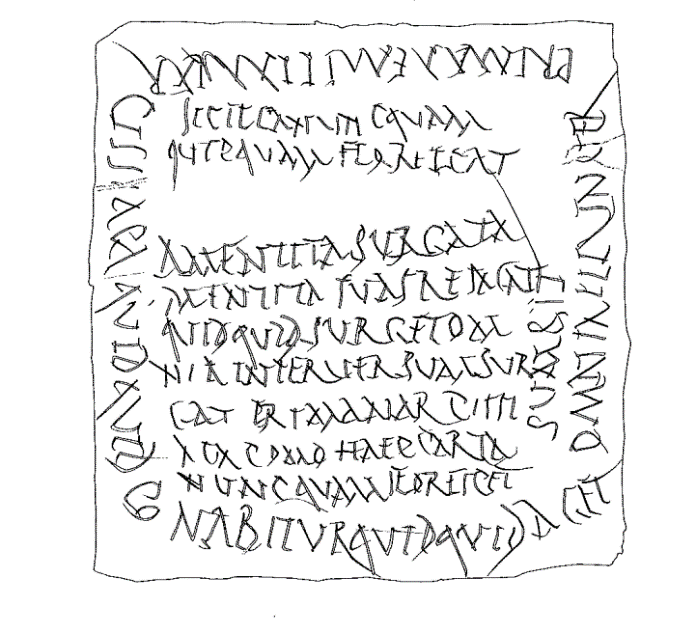

One of the most interesting curses from Mainz is DTM 15: the curse of Aemilia Prima, where this woman is doomed to never bloom again like the sheet (charta) used for cursing her. This curse is probably against Narcissus’ lover, but like in other curses from Mainz, the real motive of the curse is not explicit.

| Latin – transposed version |

Translation (Blänsdorf) |

| Prima Aemilia Narcissi agat, quidquid conabitur, quidquid aget, omnia illi inversum sit.

Amentita surgat amentita suas res agat.

Quidquid surget omnia interversum surgat Prima Narcissi aga<t>: como haec carta nuncquam florescet sic illa nuncquam quicquam florescat |

(Whatever) Aemilia Prima, (the lover?) of Narcissus may do, whatever she attempts, whatever she does, let it all go wrong. May she get up (out of bed) out of her senses, may she go about her work out of her senses. Whatever she strives after, may her striving in all things be reversed. May this befall Prima, (the lover?) of Narcissus: just as this letter never shall bloom, so she shall never bloom in any way |

An interesting feature of this curse is that the text uses a magical orientation of the script since it is partially written in a spiral counter-clockwise, creating a “verbal box”.

Figure 2. DTM 15 (from Blänsdorf et al. 2012)

We must take into account the converging and diverging features of so-called ‘curse tablets’. On the one hand, both of these two documents share an grudge towards someone, expressed through formulae that echoed the juridical style, as if the writer were making a contract with some superior being, in order to curse someone. On the other, the details are quite different: the one who stole vilbia is doomed to become liquid as water while Prima Aemilia will wither and never bloom. In one case we are dealing with a theft, in the second perhaps a bitter lover. Also, there are linguistic features which are rare and we must try to interpret, like the use of amentita that appears as a neologism, in Mainz, or vilbiam, in Roman Britain.

References

Blänsdorf, J., Lambert, P., & Witteyer, M. (2012). Die defixionum tabellae des Mainzer Isis- und Mater Magna-Heiligtums: Defixionum tabellae Mogontiacenses (DTM). Mainz.

Tomlin, R. S. O. in Cunliffe, B., Davenport, P., Care, V., & Tomlin, R. (1985). The temple of Sulis Minerva at Bath (Tab. Sulis). Oxford.

Jordan, D. R. (1985) ‘Defixiones from a well near the Southwest corner of the Athenian Agora.’ Hesperia 54.3, 205–255.

Russell, P. (2006). VILBIAM (RIB 154): Kidnap or Robbery? Britannia 37, 363-367.

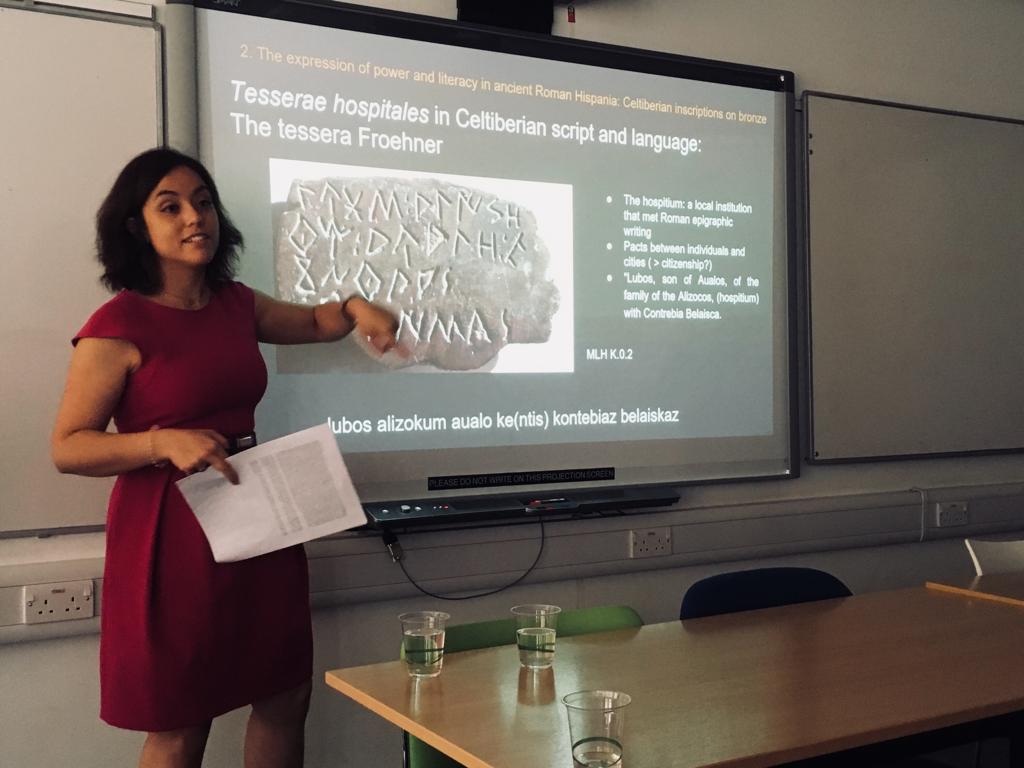

The LatinNow summer started with a training session for the Faculty of Arts at the University of Nottingham and our team on Digital techniques and resources for textual research. Led by Dr Gabriel Bodard (Institute for Classical Studies, London) and me, the DigiText workshop introduced our colleagues to four major digital approaches to humanities research: digital philology, text encoding, linked open data and linguistic annotation. The topics we covered included introduction to online resources, imaging techniques for cultural heritage, methods in digital palaeography, EpiDoc XML markup, LOD annotation, treebanking and translation alignment. While most of our examples were taken from the ancient Mediterranean, the principles and practices applied to all disciplines and cultures represented in the audience – from Scandinavian studies to modern languages translation studies. Our colleagues enjoyed a good amount of practice, starting with marking up modern gravestones in EpiDoc (the more errors and erasures the better), annotating and disambiguating place names in Recogito and aligning translations in Ugarit. Our aim was to showcase these major topics and what progress has been made in digital classics, as well as to highlight the applicability of these approaches and methodologies to virtually all textual research. We had fruitful discussions and quite a few ideas for future collaboration, both national and international – watch this space!

The LatinNow summer started with a training session for the Faculty of Arts at the University of Nottingham and our team on Digital techniques and resources for textual research. Led by Dr Gabriel Bodard (Institute for Classical Studies, London) and me, the DigiText workshop introduced our colleagues to four major digital approaches to humanities research: digital philology, text encoding, linked open data and linguistic annotation. The topics we covered included introduction to online resources, imaging techniques for cultural heritage, methods in digital palaeography, EpiDoc XML markup, LOD annotation, treebanking and translation alignment. While most of our examples were taken from the ancient Mediterranean, the principles and practices applied to all disciplines and cultures represented in the audience – from Scandinavian studies to modern languages translation studies. Our colleagues enjoyed a good amount of practice, starting with marking up modern gravestones in EpiDoc (the more errors and erasures the better), annotating and disambiguating place names in Recogito and aligning translations in Ugarit. Our aim was to showcase these major topics and what progress has been made in digital classics, as well as to highlight the applicability of these approaches and methodologies to virtually all textual research. We had fruitful discussions and quite a few ideas for future collaboration, both national and international – watch this space!

Fieldwork in some challenging conditions in Kent

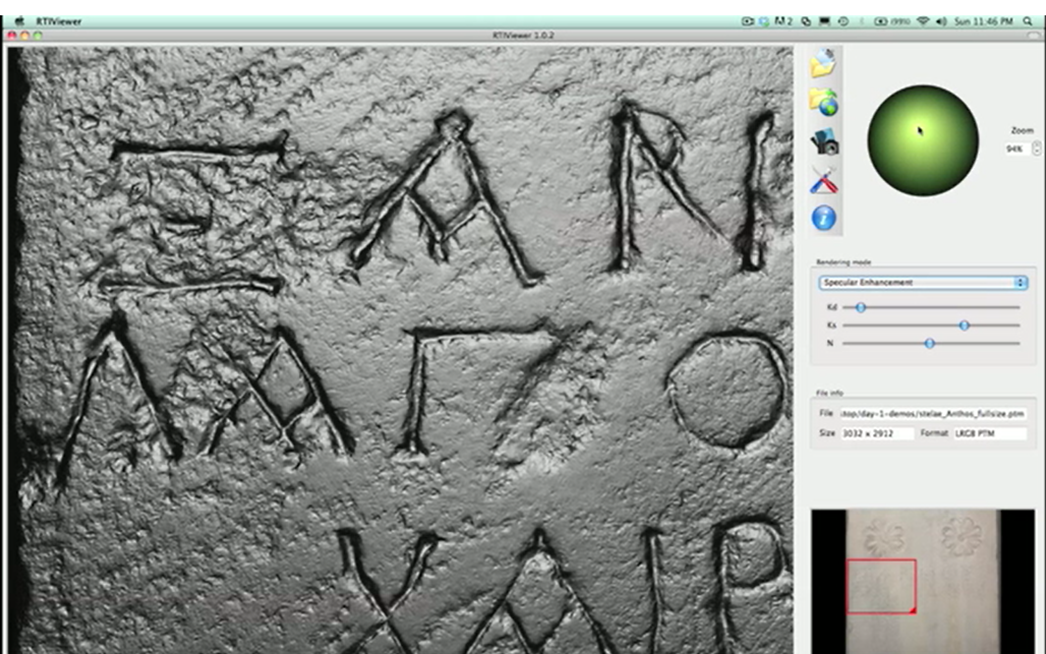

Fieldwork in some challenging conditions in Kent Reflectance Transformation Imagining viewer showing section of Greek text

Reflectance Transformation Imagining viewer showing section of Greek text