By Francesca Cotugno

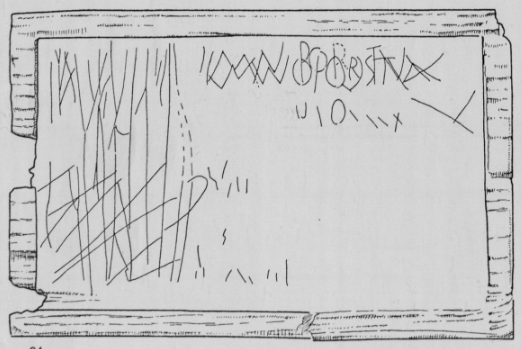

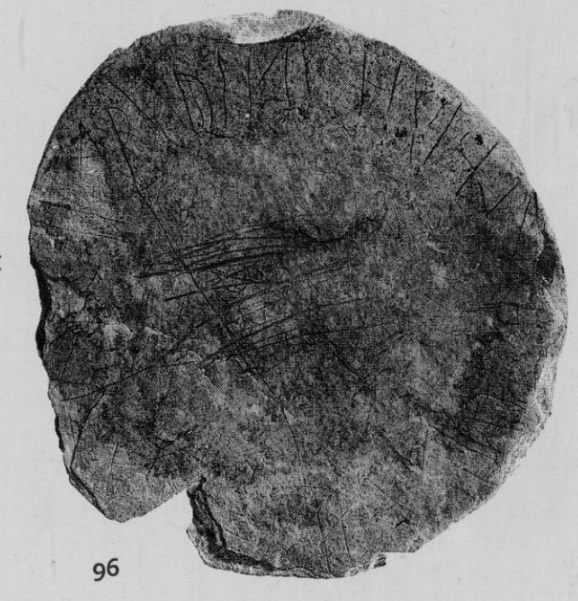

From the Germanies it is possible to record direct evidence of education. At Velsen, the old Flevum, a Tiberian fort in the Netherlands, there is what may be the oldest abecedaria in Germania. It was written on a wooden barrel, which originally contained wine (Bosman 1999: 92). Writing on this type of material has also been found in the writing tablets from Londinium-Bloomberg and in Roman Britain there is evidence of abecedaria from London and writing exercises have been found in the auxiliary fort of Vindolanda. On the continent, other abecedaria and writing exercises have been found in the vicus of Sulz am Neckar (see figures 1 and 2). Also, a roof tile from a piece of slate from Frankfurt-Heddernheim represents another abecedarium found in the Germanies (Matijevi? 2015, Reuter and Scholz 2004: 62–63).

Figure 1: Writing exercise on clay from Sulz am Neckar (source: Reuter and Scholz 2004)

Figure 2: Writing exercise on tablet from Sulz am Neckar (source: Reuter and Scholz 2004)

Figure 3: abecedarium from Frankfurt-Heddernheim (source Reuter and Scholz 2004)

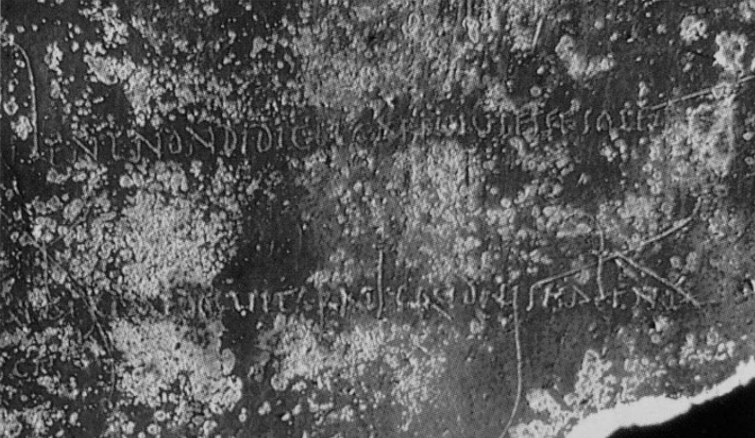

Beside a quite basic education, based on learning the graphemes of the Latin alphabet, it is noticeable that the education was based also on writing down passages of Classical texts, as reflected in the Virgil quotation from the Aeneid on a brick from Unter-Eschenz in the canton of Thurgau (see Figure 4, Reuter and Scholz 2004: 63).

Figure 4: Classical text from Ziegel aus Unter-Eschenz, canton of Thurgau (source: Reuter and Scholz 2004)

In particular, the poet Virgil was extensively used for elementary instruction and there are evidences from other parts of the Roman Empire. This kind of writing exercise has been found also in some of the writing tablets from Vindolanda (Tab.Vindol. 118 and 452). Tab.Vindol. 118 (see figure 5), for example, reports the verse Aeneid 9, 473 interea pauidam uolitans pinnata per urbem, but failed in rendering the last part of the sentence (pinnata dubem) (Bowman and Thomas 1983).

Figure 5: Classical text from Tab.Vindol. 118 (https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/TabVindol118)

Coming back to the Germanies, it is possible to make reference to another evidence of school life in this area. It is an interesting exchange between a student and his teacher dating between 2nd–4th CE. The exchange is recorded on the wall plaster of a Roman villa in Ahrweiler (Reuter and Scholz 2004: 63) and indicates that the difficulties sometimes experienced in education are nothing new.

On this wall plaster we can still read (see figure 6):

Qui bene non didicit carrulus esse solet

scribtum me docuit Grati crudelis habena

The sentences can be translated as follows:

‘He who has not learned well, tends to be a chatterbox

The belt of cruel Gratus taught me what is written [above]’

Figure 6: Wall plastering from Ahrweiler (source: Reuter and Scholz 2004)

In LatinNow we are looking at the up-take of Latin and literacy in the provinces and evidence for education is crucial for understanding this. These scattered testimonia will form part of the difficult evidence we have to contextualize to explore the nature of schooling in the Roman world.

References:

Bosman A. V. A. J. (1999), Battlefield Flevum: Velsen 1, the latest excavations, results and interpretations from features and finds, in Schlüter and Wiegels (eds.), Rom, Germanien und die Ausgrabungen von Kalkriese: Internationaler Kongress der Universität Osnabrück und des Landschaftsverbandes Osnabrücker Land e. V. vom 2. bis 5. September 1996, 91–96. Osnabrück, Landschaftsverband Osnabrücker Land.

Bowman A. K. and Thomas D. (1983), Vindolanda: the Latin writing tablets. London, Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies.

Matijevi? K. (2015), Writing and Literacy/Illiteracy, in James and Krmnicek (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Roman Germany. Oxford, Oxford Handbooks Online.

Reuter M. and Scholz M. (2004) Geritzt und entziffert: Schriftzeugnisse der römischen Informationsgesellschaft. Stuttgart, Theiss

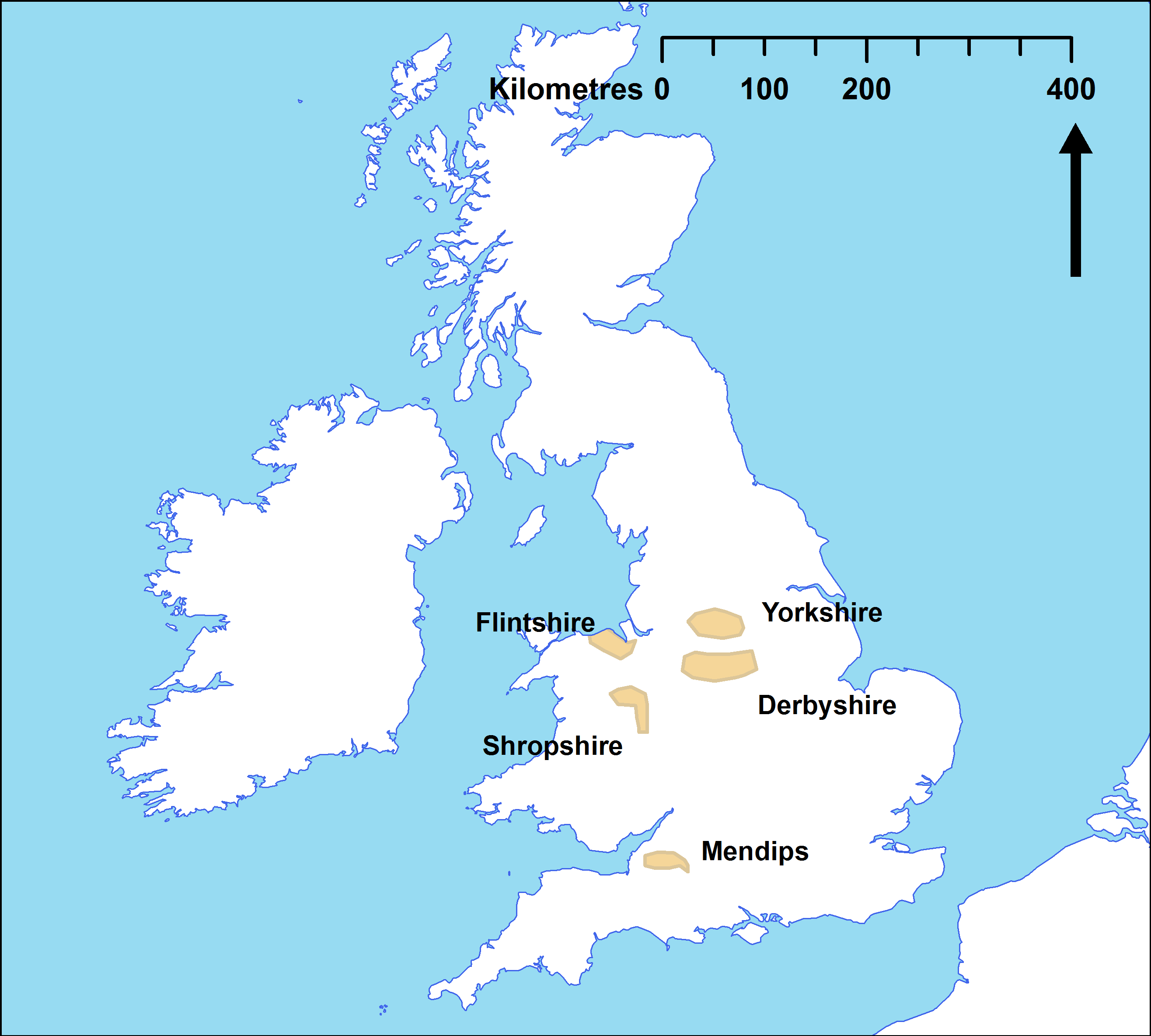

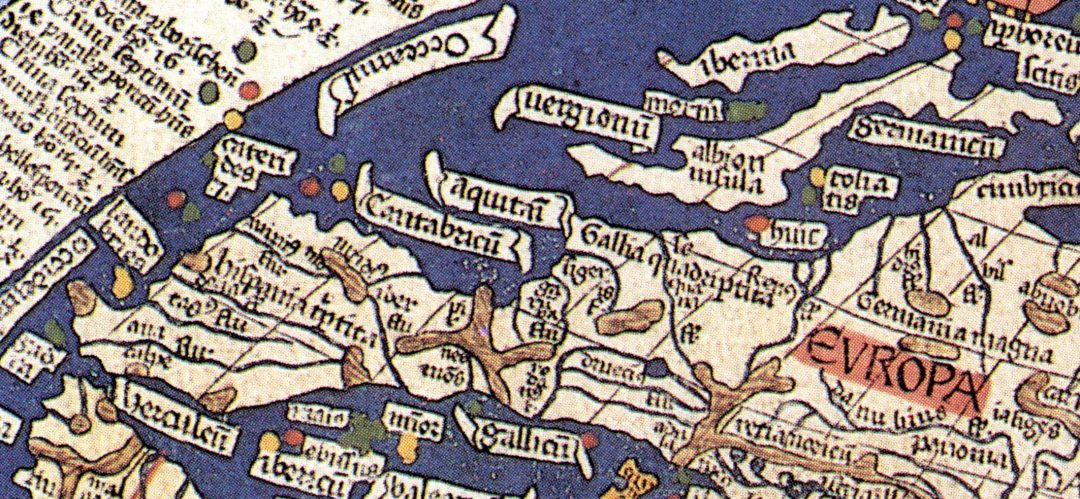

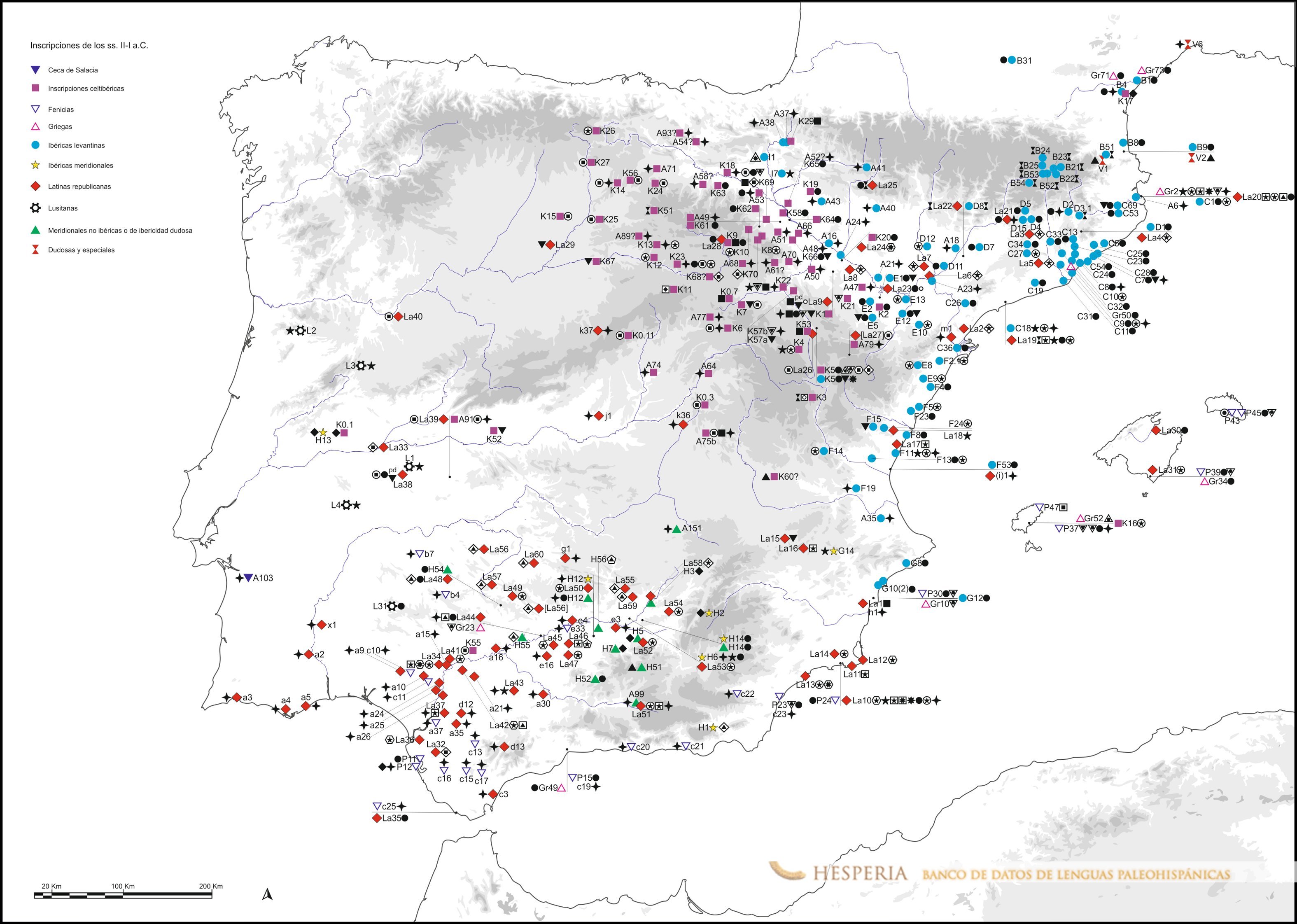

Map from

Map from