By Alex Mullen

St Andrews was deluged with Classicists in mid-July for the Celtic conference in Classics. The atmosphere was one of scholarly fun and I even skipped nearly the entire ceilidh (I adore ceilidhs – awesome organized fun!) because I got into a debate about, essentially, ‘archaeologizing’ epigraphy.

This was a direct result of the panel: ‘(Un)set in stone’ on fresh approaches to epigraphy at which Eleri Cousins (St Andrews) was keen to get us to think about innovative ways to treat epigraphy. I could only attend the first day but it was clear that she had brought together a set of people with diverse and complementary interests, including those who were not primarily epigraphists and even, goodness, a non-classicist! Eleri had instructed me to present something ‘theory driven’ and it was great to spend some time before the conference thinking about how to talk in this specific context about the theory, methods and concepts that guide my research, in this case a discussion of Gaulish, the Celtic language of Gaul.

About a decade ago Carrie Vout (Cambridge) asked me at an interview ‘What is interdisciplinarity?’. One of those questions that’s easy to ask but so difficult to answer. I think I’ve spent the last decade working it out. Although my answer at the time, something along the lines of ‘It’s when you integrate not just the evidence from a range of disciplines, but also the methods and approaches’, hasn’t changed that much, I feel I now might practise what I preach. Indeed, Eleri’s panel and the discussions afterwards made me wonder how unusual I might still be in my close engagement with several of the disciplines within Classics. This is thanks to my broad undergraduate degree, when I began to specialise in Indo-European linguistics, sociolinguistics and ancient history, graduate training which added Celtic linguistics and investigations into the material culture of the Iron Age and Roman West, and the luxury of years of Research Fellowships which allowed me to pursue archaeology properly. I might not have realised it at the time but marching up and down fields strapped into geophysics equipment humming tunes to keep pace indirectly transformed my research. By becoming ‘also an archaeologist’ not only do I understand the discussion of material culture better, but attending the conferences, discussing issues at dinners, collaborating on projects has made me think in more interdisciplinary ways. And it has made me an advocate of broad and deep classical training in our Schools, Higher Education and beyond.

Fieldwork in some challenging conditions in Kent

Fieldwork in some challenging conditions in Kent

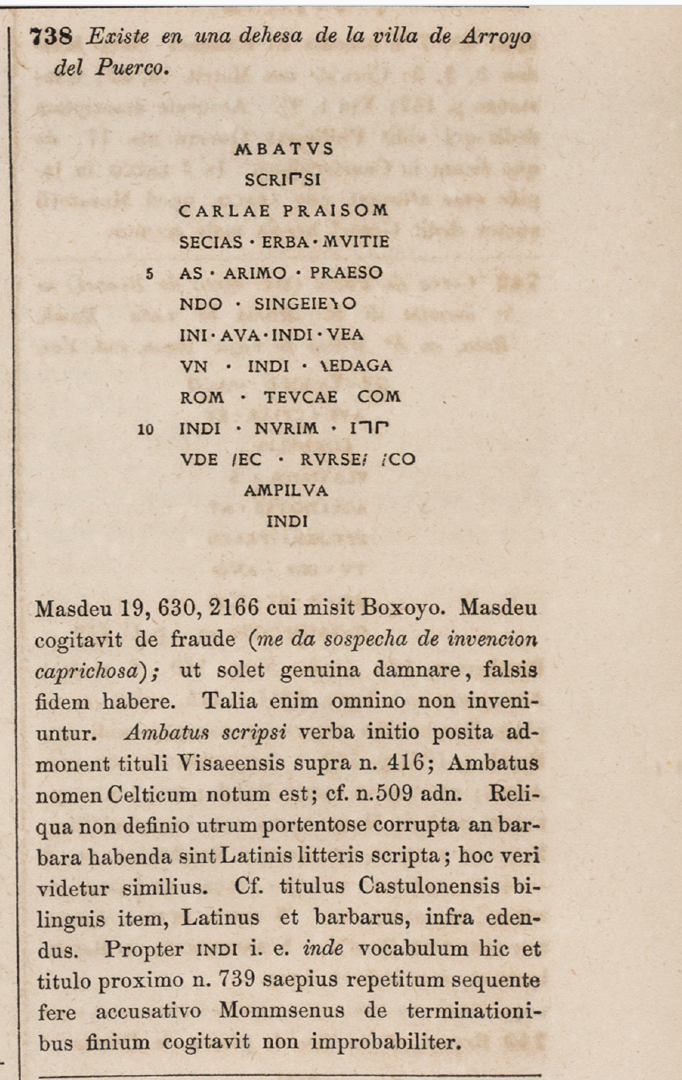

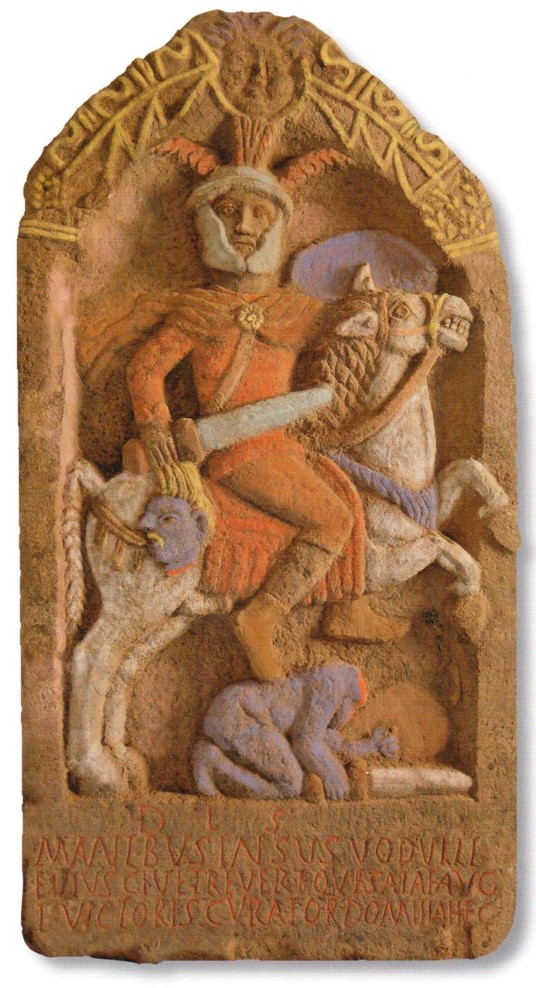

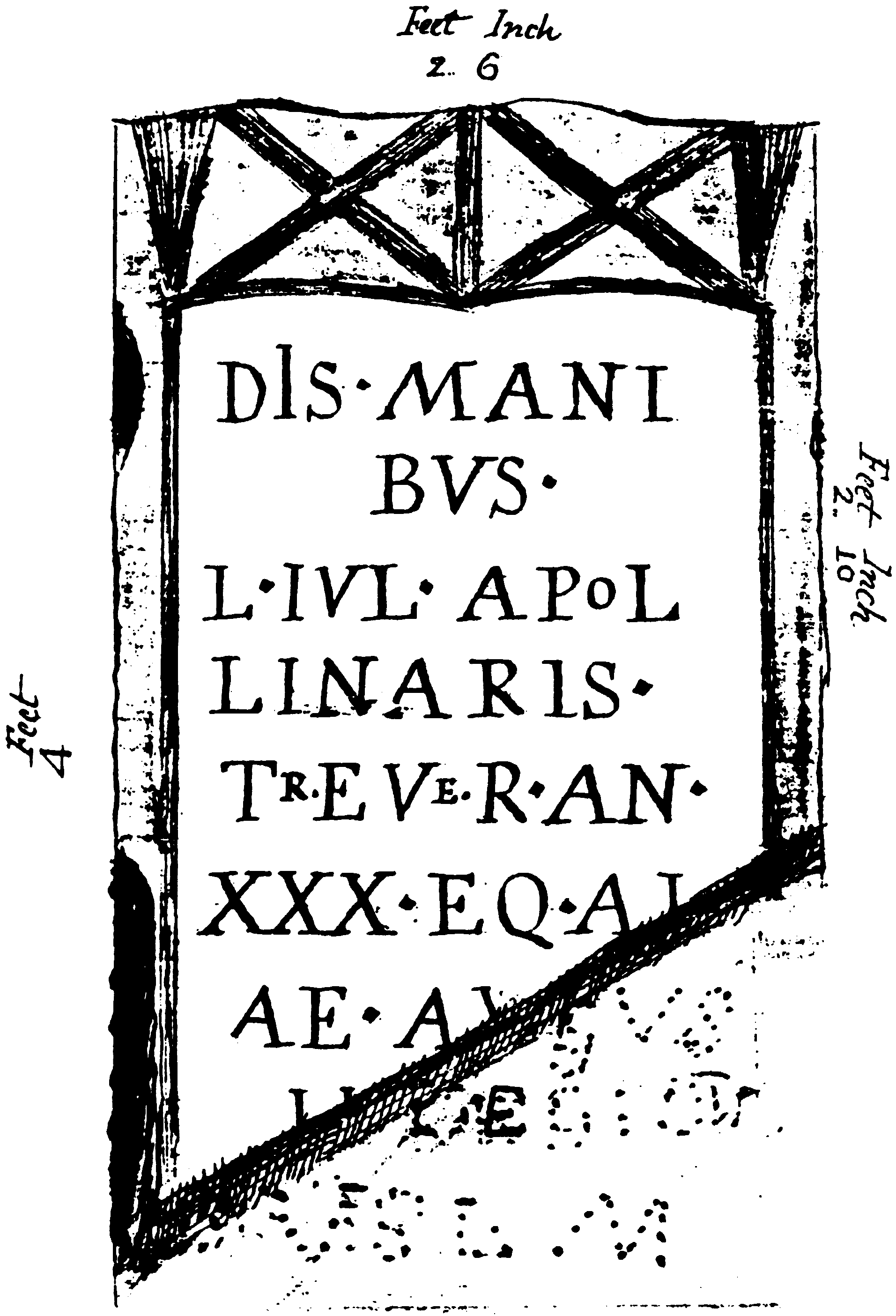

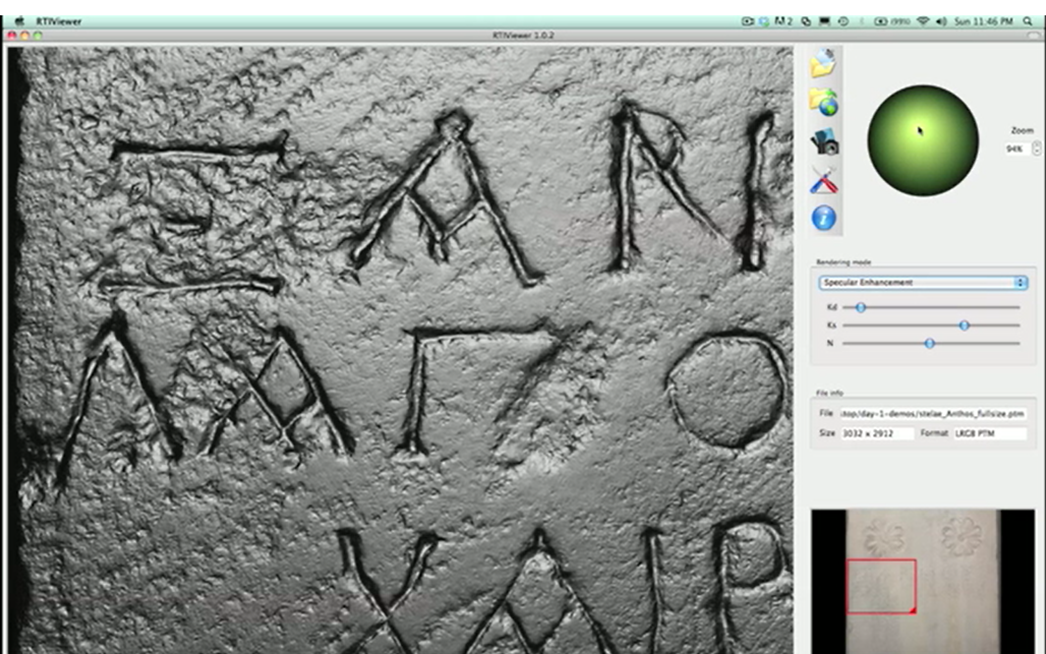

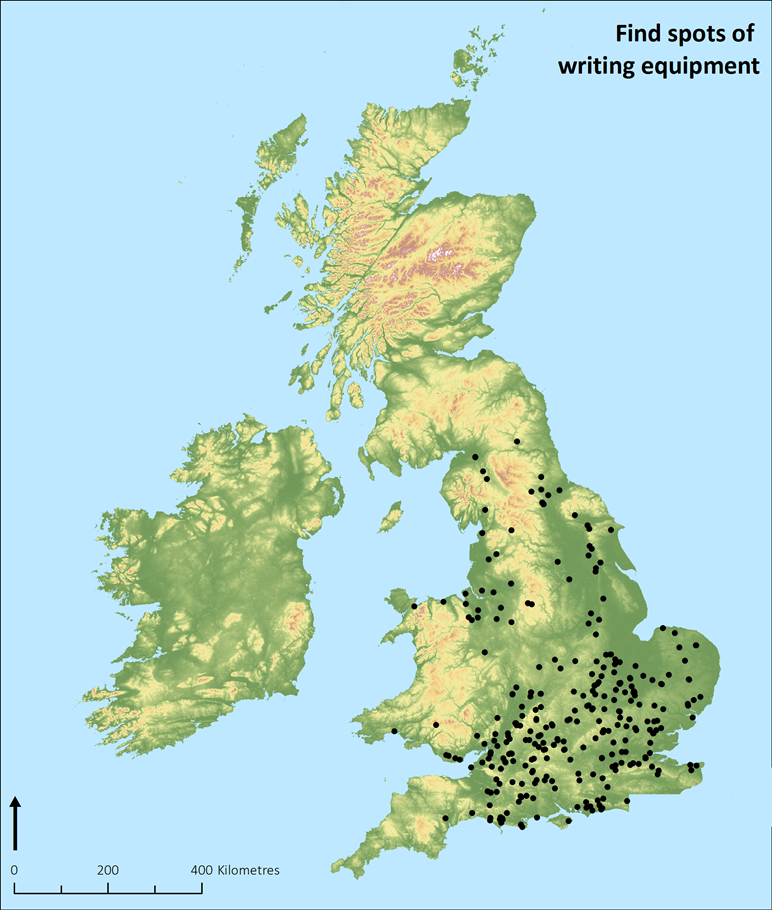

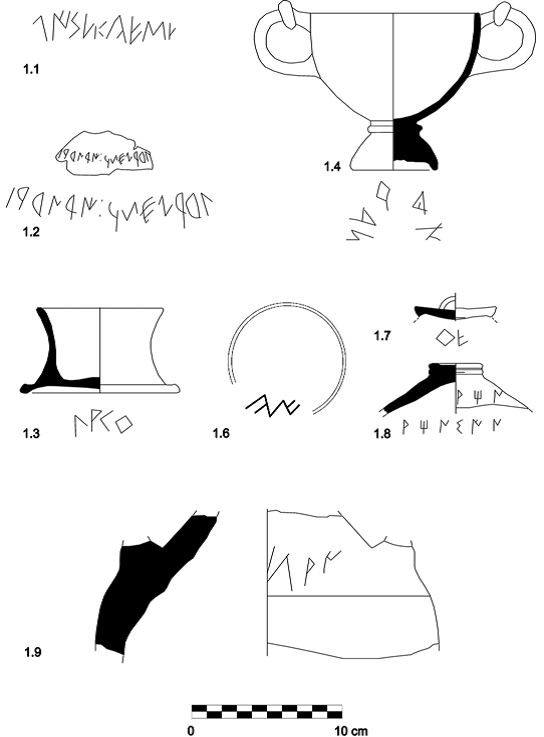

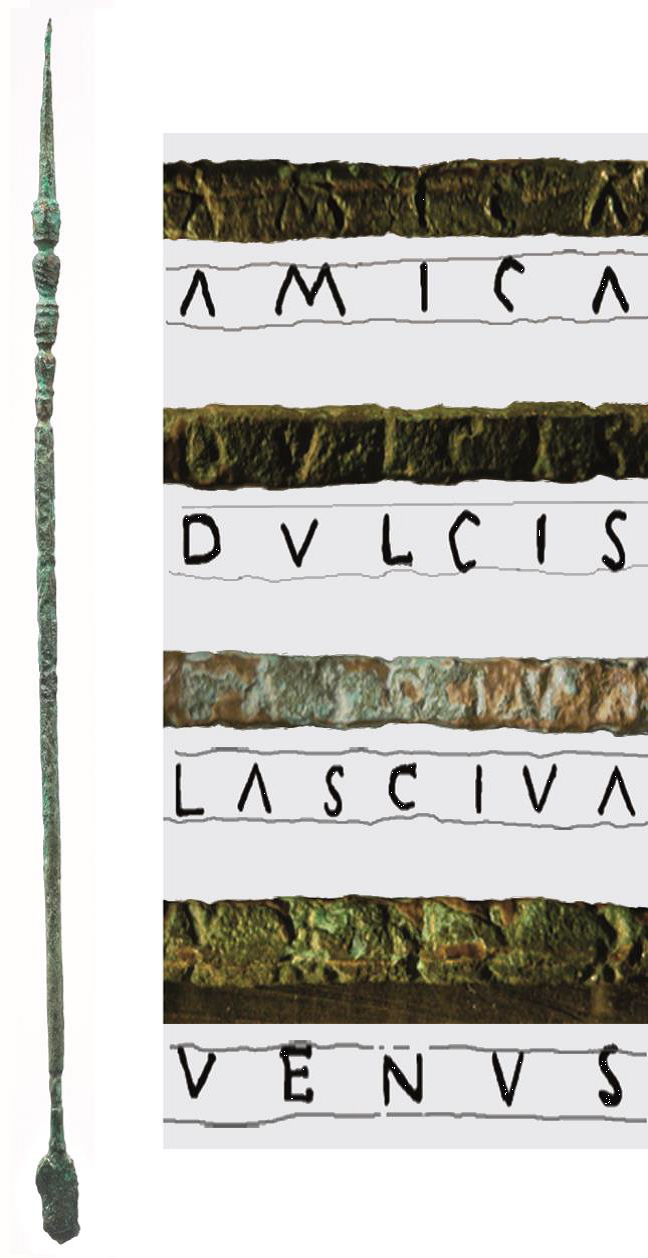

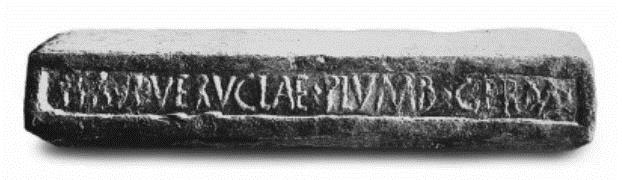

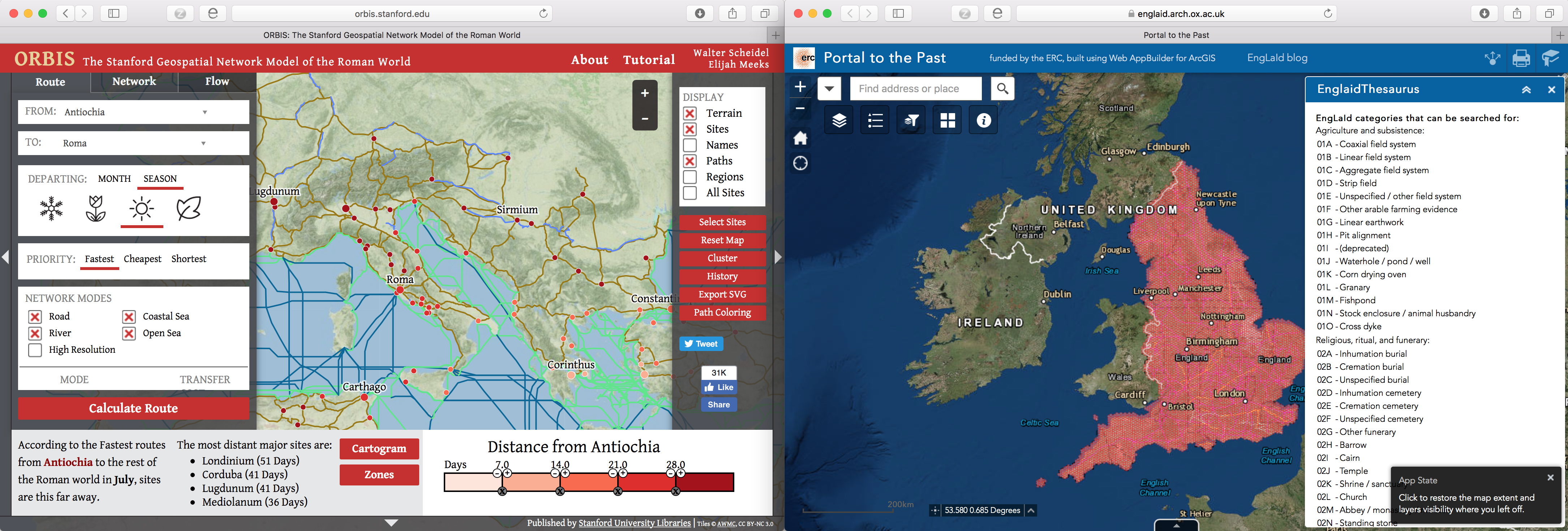

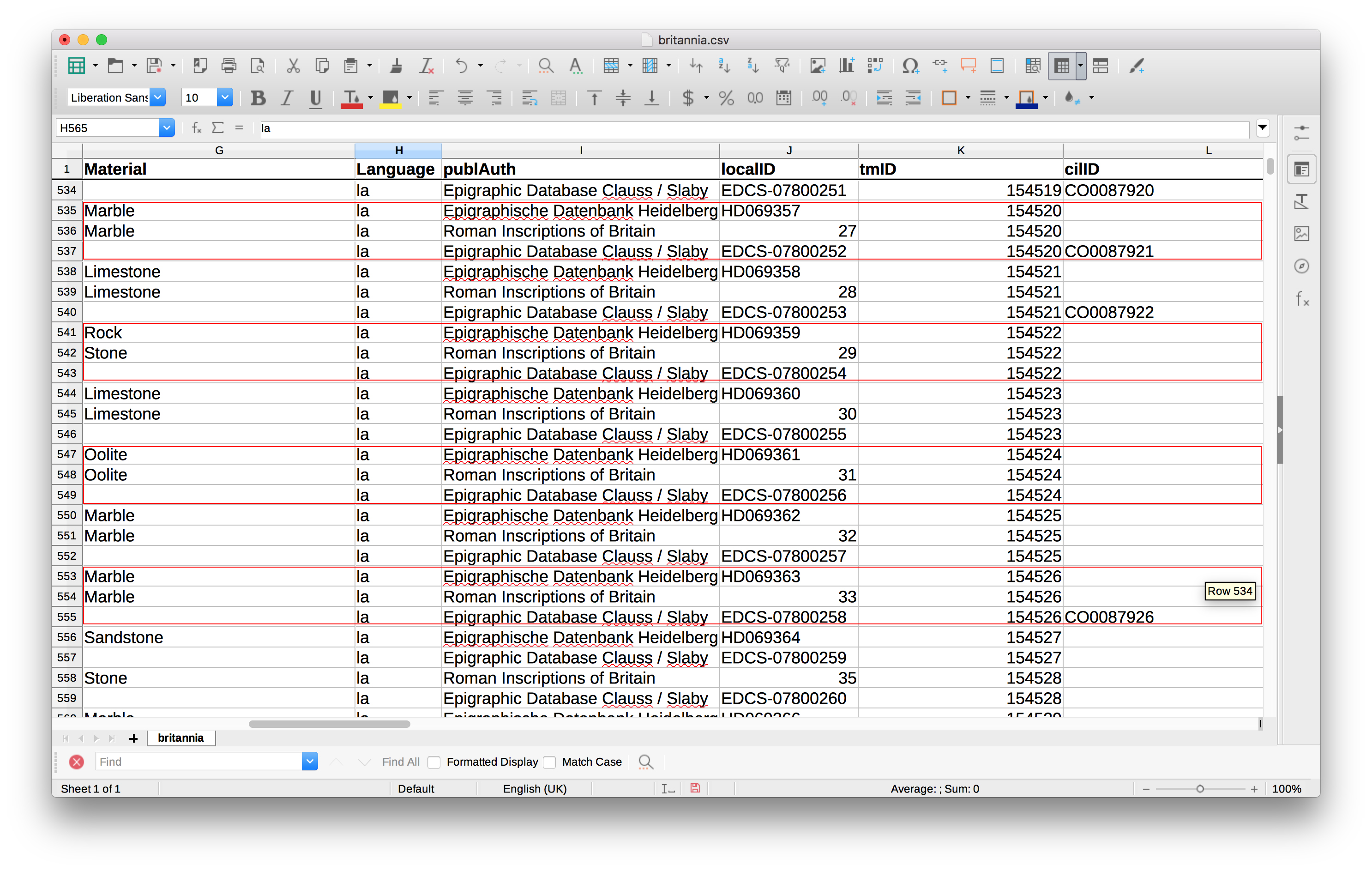

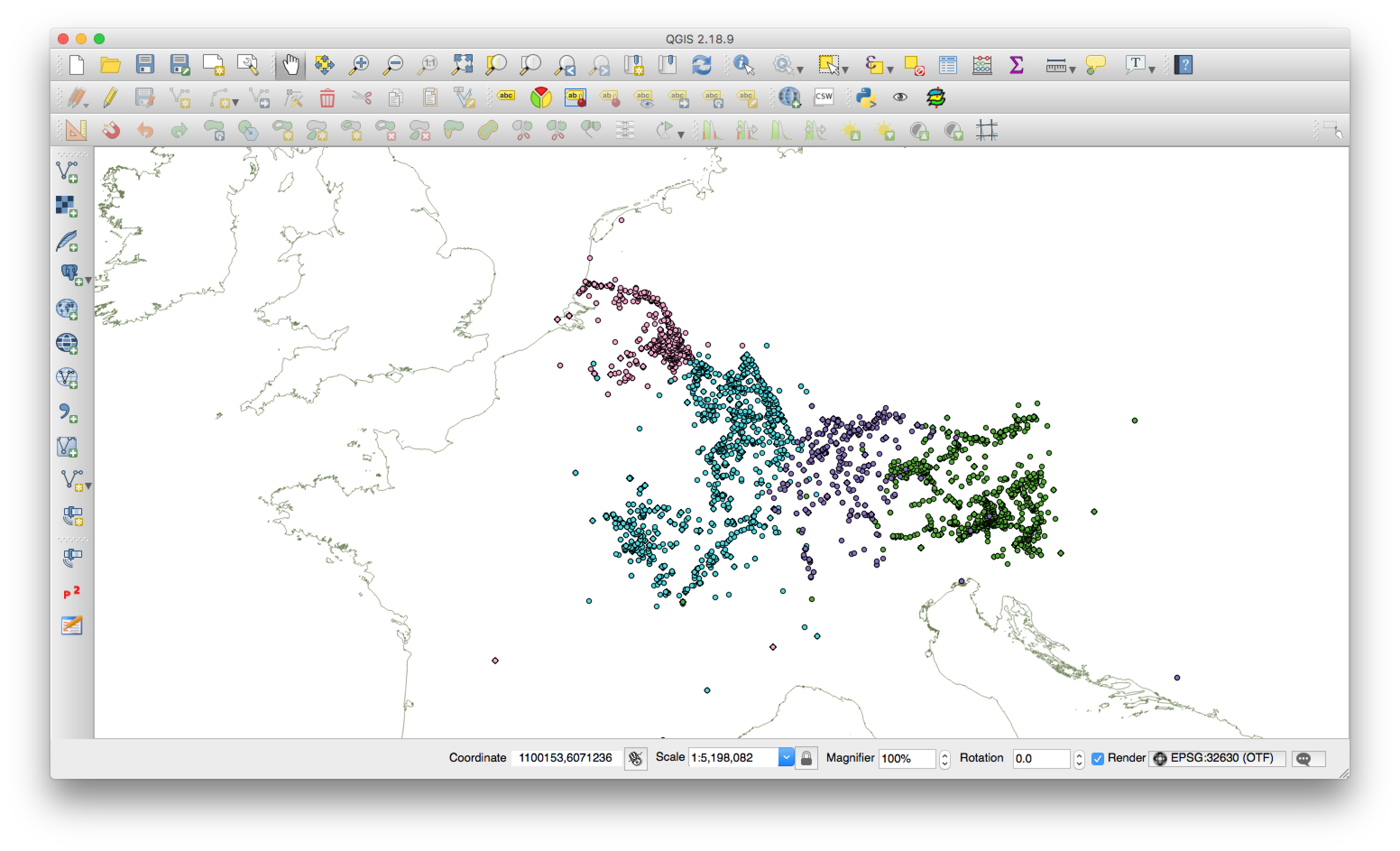

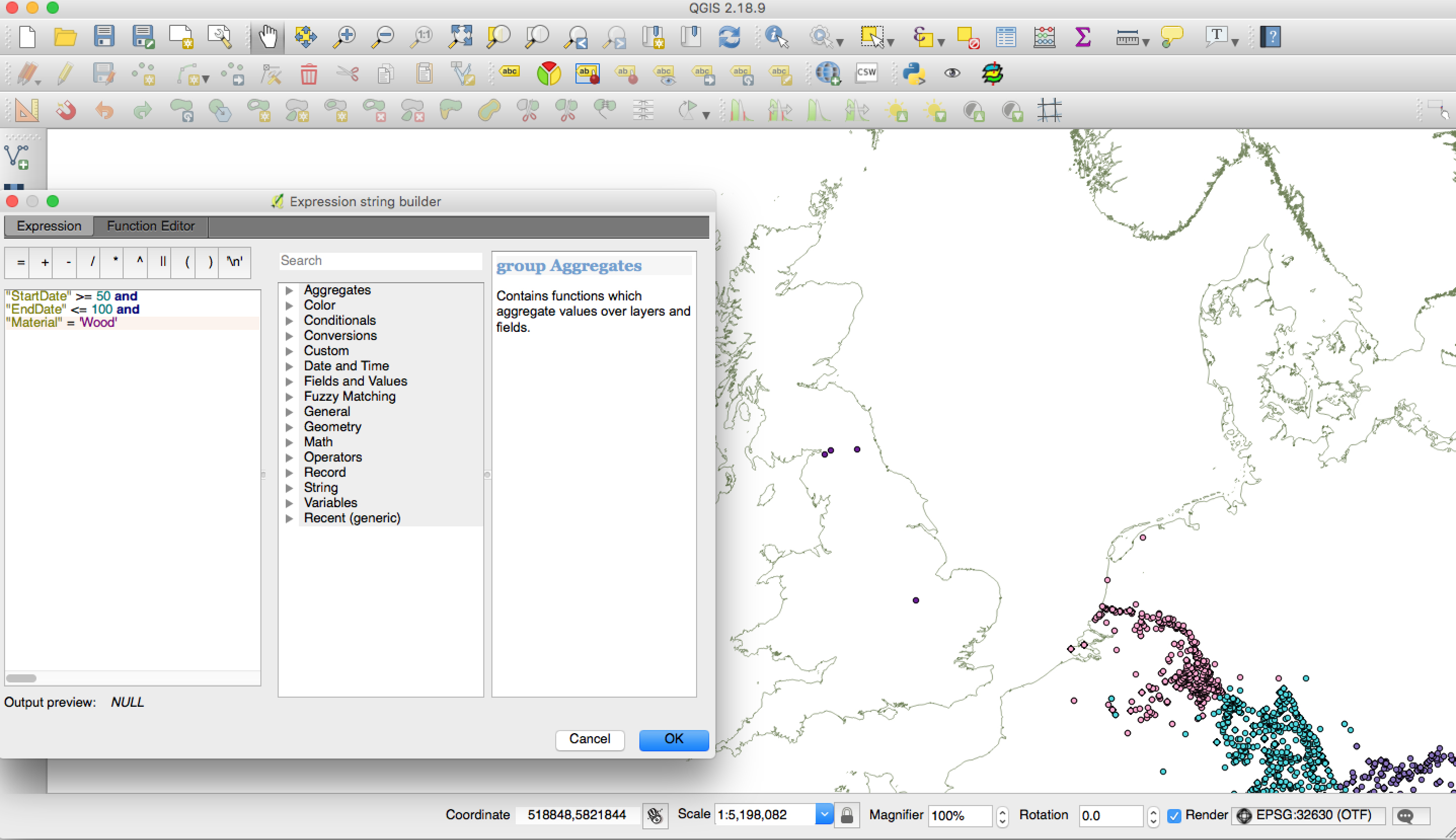

Prompted by Eleri, in the talk I discussed what you could term ‘an archaeological approach to epigraphy’. Naturally this could integrate key approaches in archaeology, for example appreciation of materiality (focus on the object and its relations to human practice), context (at all scales) and phenomenology (the experience of creating, displaying, viewing etc.), but also tools used by archaeologists, such as petrological analysis, RTI or GIS to coordinate a range of data. Perhaps, however, what might be most useful to adopt in epigraphy from modern practices of archaeology is the constant questioning of assumptions and weighing up of possible interpretations driven by self-analysis and criticism. Many epigraphists do this, of course, but perhaps not with the level of care and rigour of those trying to make material culture ‘speak’. Texts can make us think they are telling us what we need to know, and we need to question that every time.

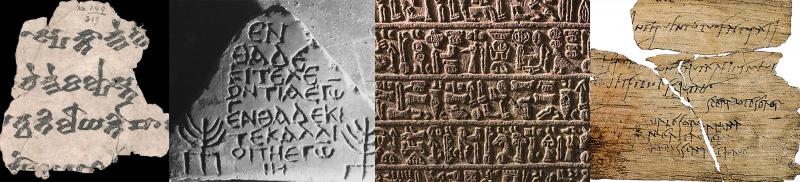

Reflectance Transformation Imagining viewer showing section of Greek text

Reflectance Transformation Imagining viewer showing section of Greek text

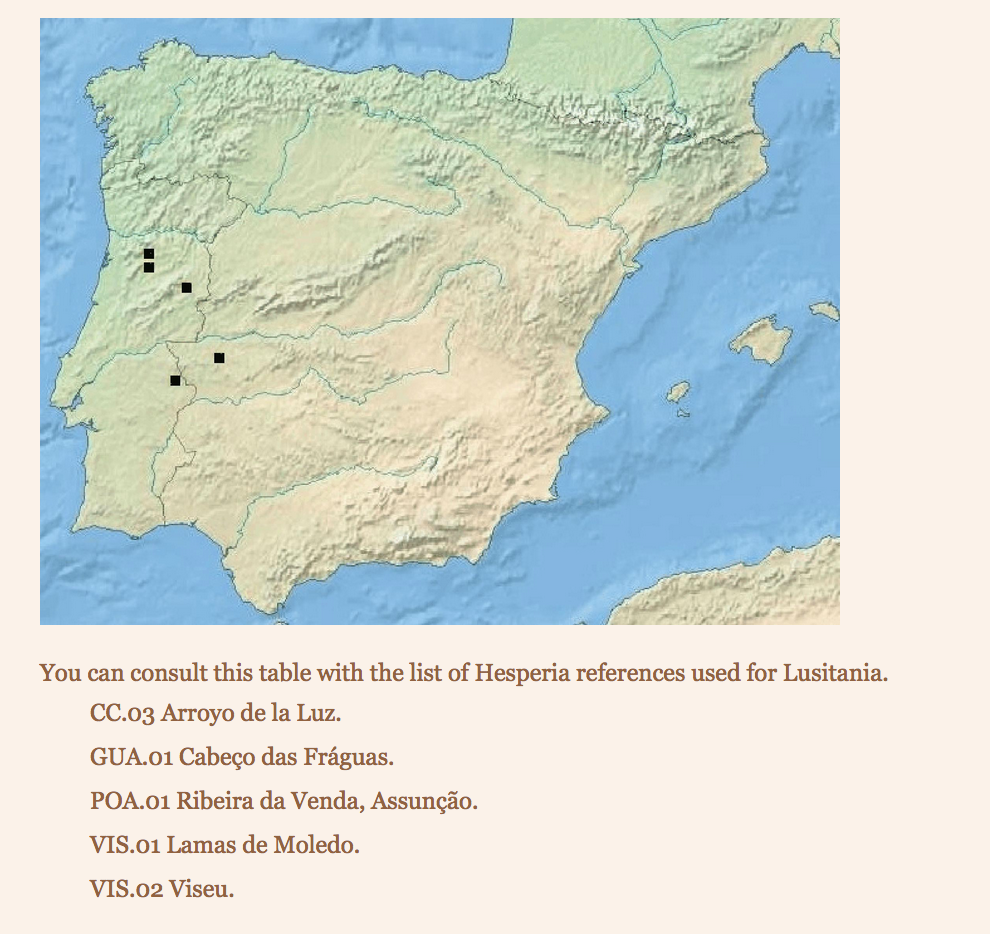

Fig. 2. Map of the Lusitanian inscriptions according to Hesperia Database.

Fig. 2. Map of the Lusitanian inscriptions according to Hesperia Database.