By Alex Mullen

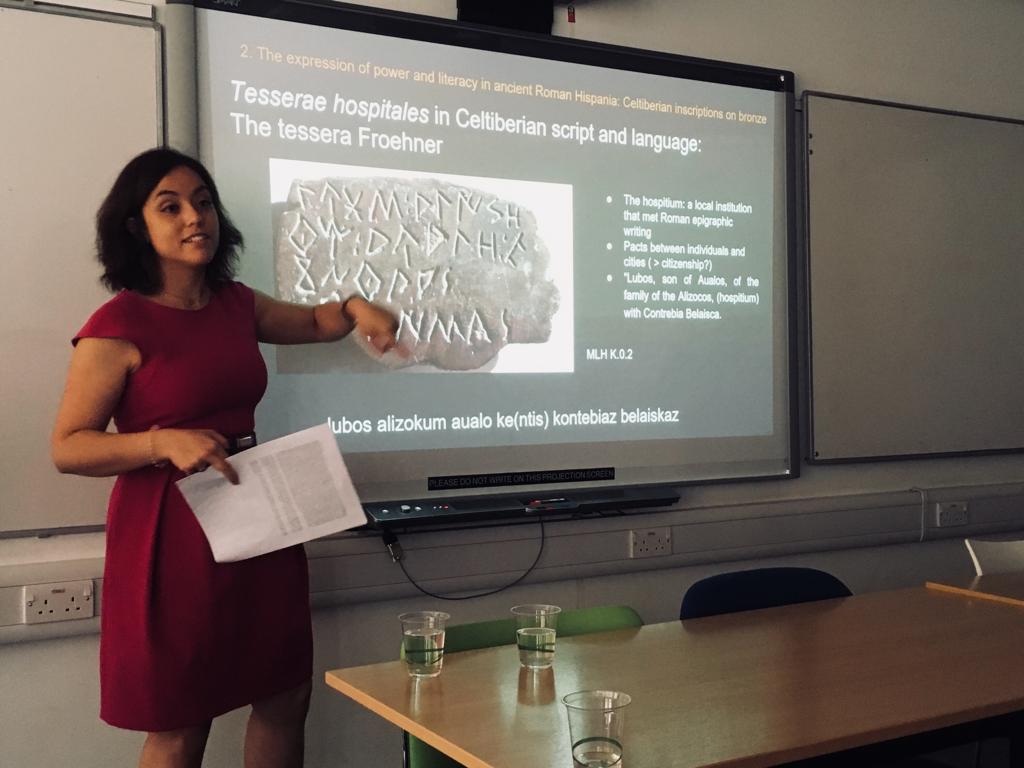

The last few days we’ve been working hard again on our epigraphic database. We have just released a video which describes a little how we will use this in combination with our other datasets to try to answer some big historical questions about life and languages in the Roman west. It’s a talk Pieter (in the Netherlands) and I (in the UK) gave jointly on a Friday night for the Digital Humanities centre at San Diego State University. We had a great host – David Wallace-Hare (the David I occasionally mention in the talk!) – to whom our thanks for the invitation. It was nice to be asked to talk specifically about the DH side of our project.

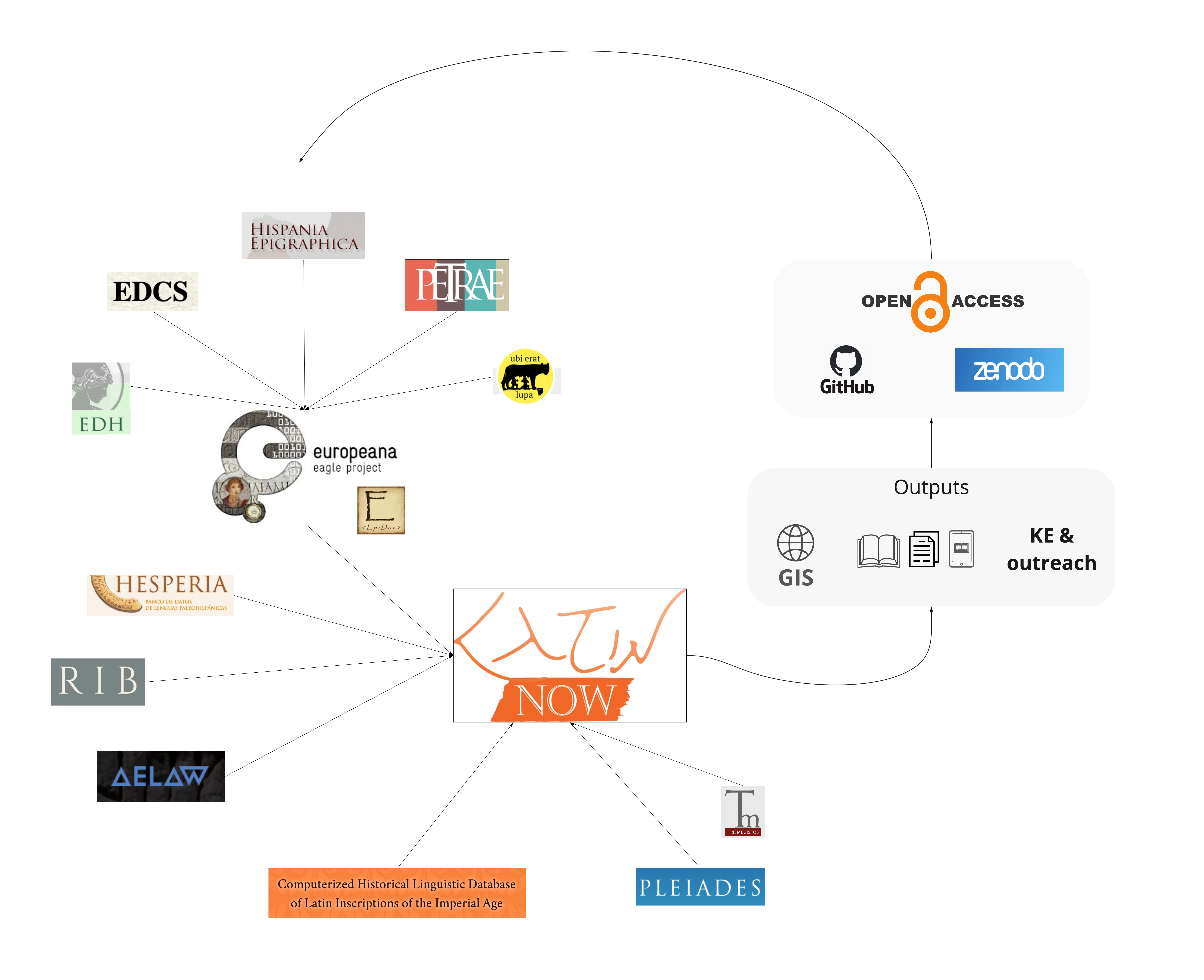

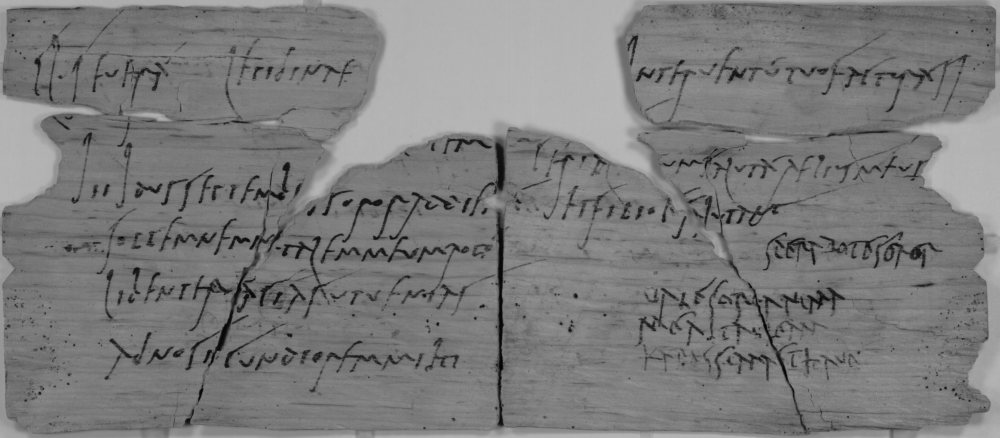

In our last blog, we explained the nature of our epigraphic dataset and some of our tasks over the past couple of years. We are now very close to pressing the button to initiate ‘The Great Merge’. Up until this point we have been working with 181,000+ different EpiDoc records mostly from EAGLE which are derived from a number of digital epigraphic sources. Over the last couple of years we have identified, by machine and by hand, many thousands of duplicate records (in addition to the numerous duplicates already found by EAGLE). Now we will merge these records to make one set of records (c. 135,000) for each text-bearing object and will assign them LatinNow URIs. All the original data will, of course, also be kept. And everything will be open access.

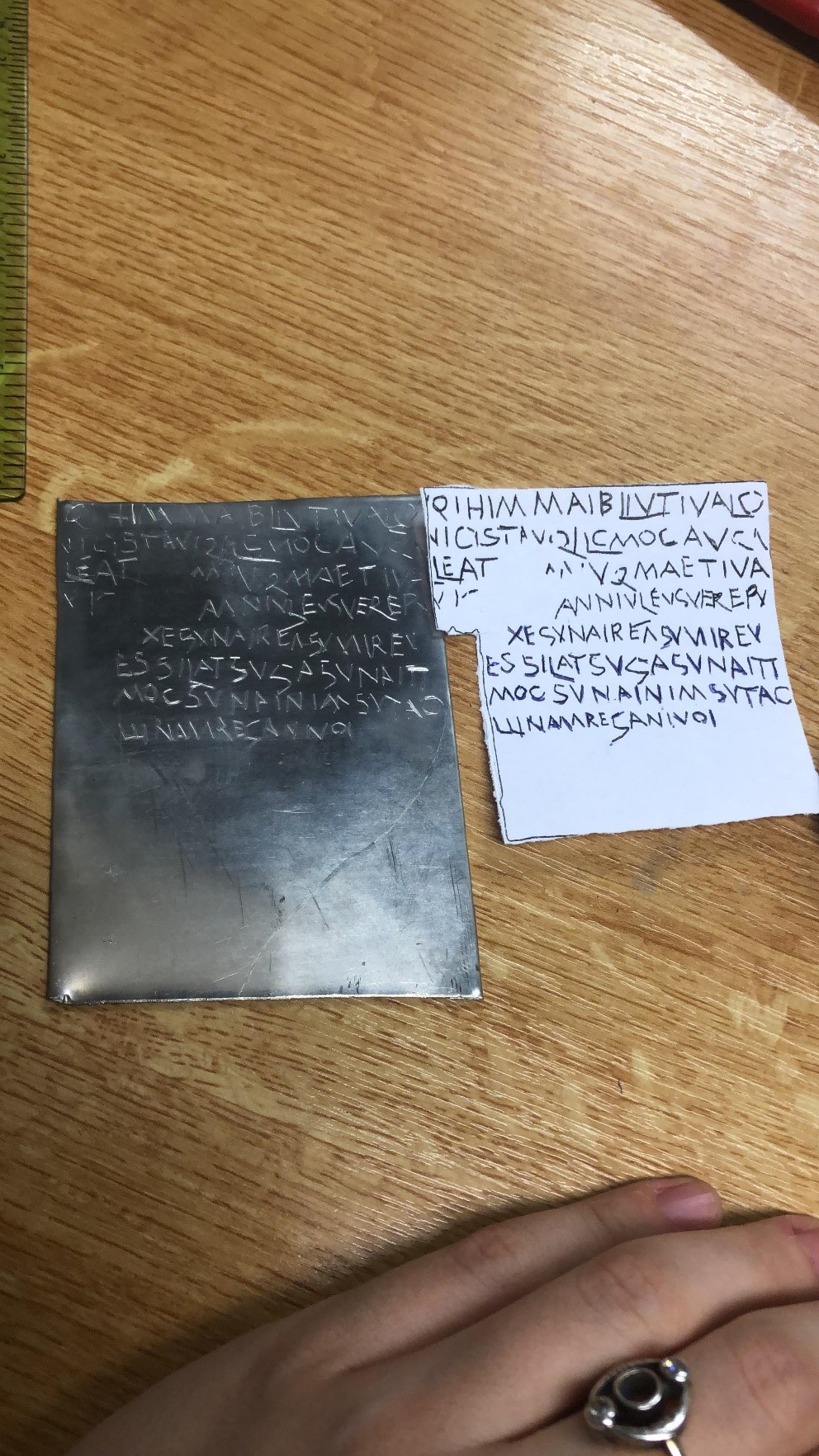

Merging records might sound straightforward but what goes into the single merged record is complicated and requires even more complicated coding (the latter our wonderful Technical Director’s specialty thankfully!). Everything is fine if the attributes in each record match or one provides metadata that the other doesn’t. The issue is when the values for the same attribute in the duplicate records don’t match. The first pass at the merge coding turned up a scarily high number of non-matching attributes, over 24,000, even after our attempts at harmonizing the vocabularies and cleaning of the dataset. Luckily a good chunk of these are solved by adding rules about hierarchy (‘stone’ and ‘stone: limestone’ are not conflictual) and telling the machine how to cope with the same attributes which been assigned differing levels of confidence. Many of the non-identical attributes are also complementary – so we can tell the code to keep both of them when merging the records. But there, as always, remains a set of ‘problematic cases’. It is unlikely, for example, that the same inscription is simultaneously ‘stone’ and ‘ceramic’ (perhaps a researcher in one of the source epigraphic databases has assumed votive texts with VSLM will be on stone for example), and inscriptions are rarely both a milestone text and an epitaph. We have had to find clever ways to deal with these but many must be checked by hand.

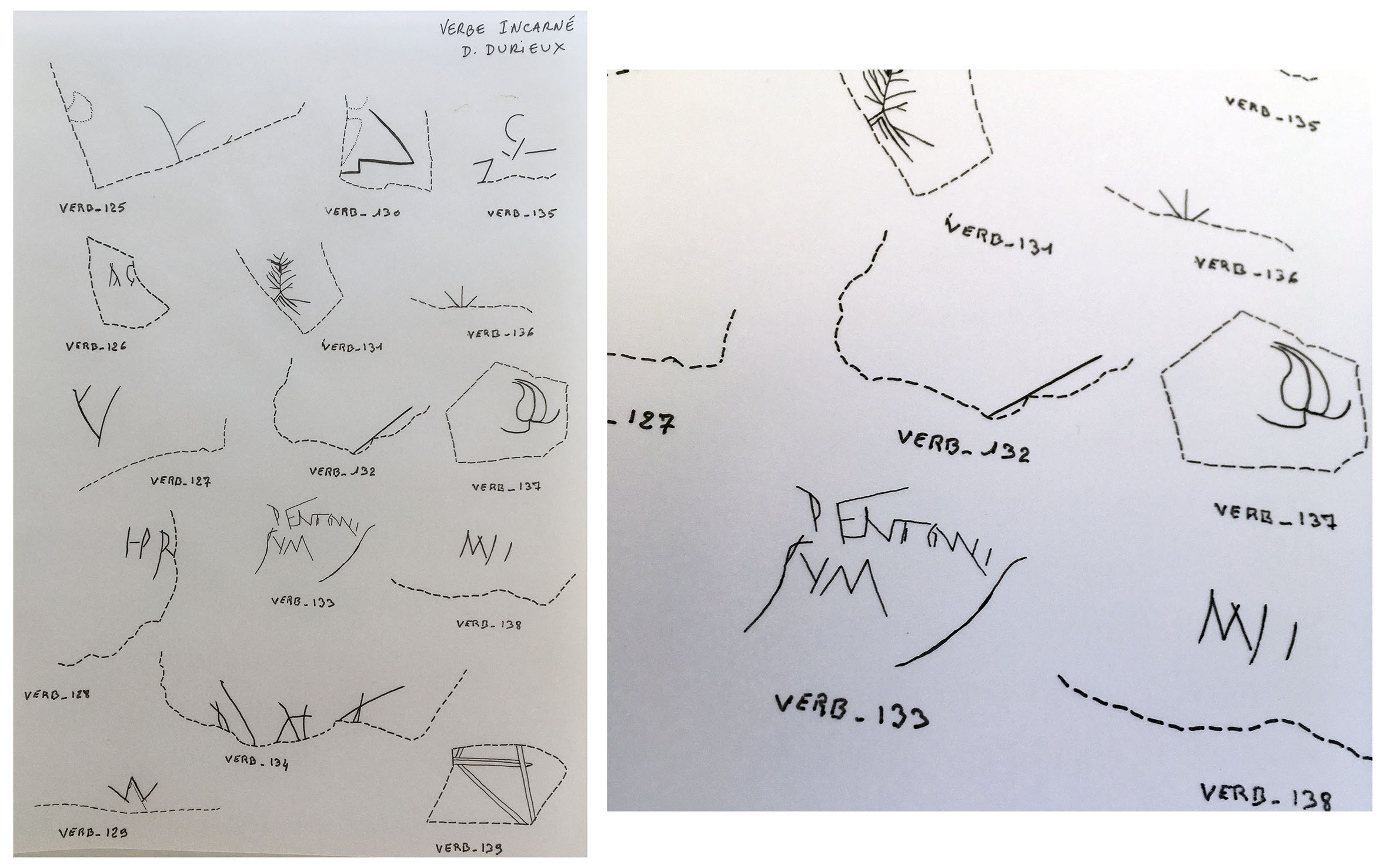

One example may serve as an indicator of some of the knotty issues we face. As ancient historians we are interested in mapping the lapidary epigraphic habit so it is important that we have a reliable set of georeferenced data points of stone inscriptions. A few stone inscriptions have the attribute ‘material: rock’ in the database. Of course stone is also rock, but epigraphers do normally want to make a distinction. Worked rock – what we call stone – made into an object that is then inscribed (e.g. a tombstone or an altar) is different from rock in a cave or mountainside that is carved or scratched into directly. There are interesting links to make between the two formats, but we want to be able to categorize them separately and not subsume the rock inscriptions into the much larger lapidary set. We can of course keep rock within the series of attributes for the material of lapidary texts, for example having rock, stone and limestone in a descending hierarchy.

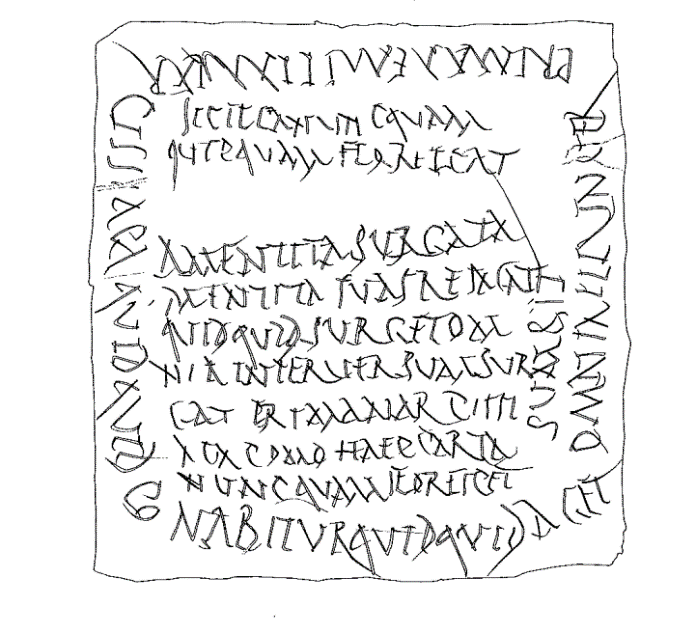

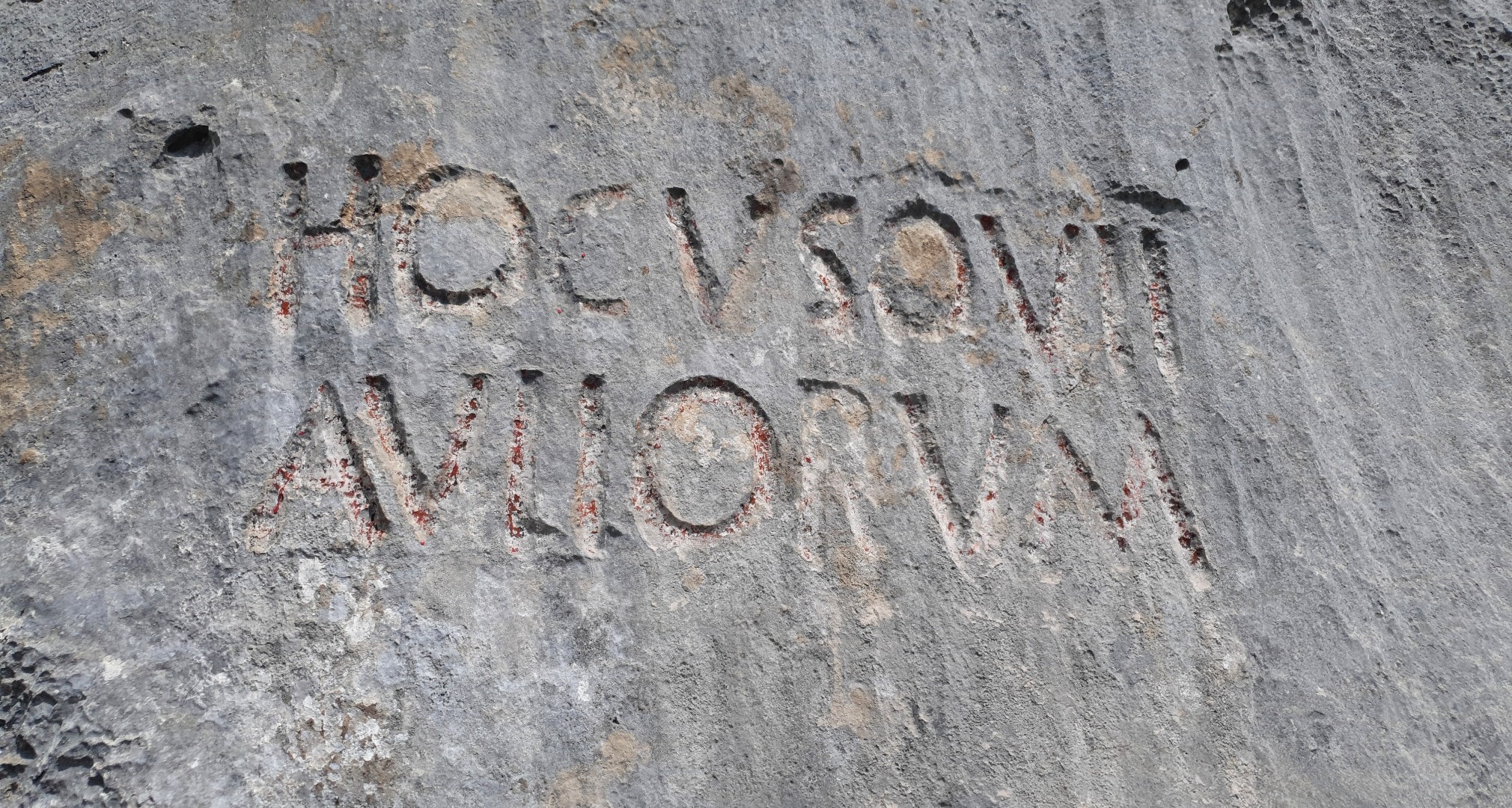

One of our fun tasks this past week was trying to ensure the rock and stone inscriptions were not lumped together. Pieter took on the Iberian Peninsula, Anna the Germanies and I Gaul and Britain. This led me to rediscover some really interesting rock texts, including the slightly unusual text on a rock face of the crête de Malissard, which reads hoc usque Aveorum, which can be translated roughly as ‘this is the border of the territory of the Avei (?)’ and shows the double I for E which is much more common in handwritten texts using the stylus than in rock or stone-carved texts. Who the Avei (?) might be is unclear. It’s an intriguing inscription to which I’d like to return, and perhaps even try to visit one day when travel is permitted.

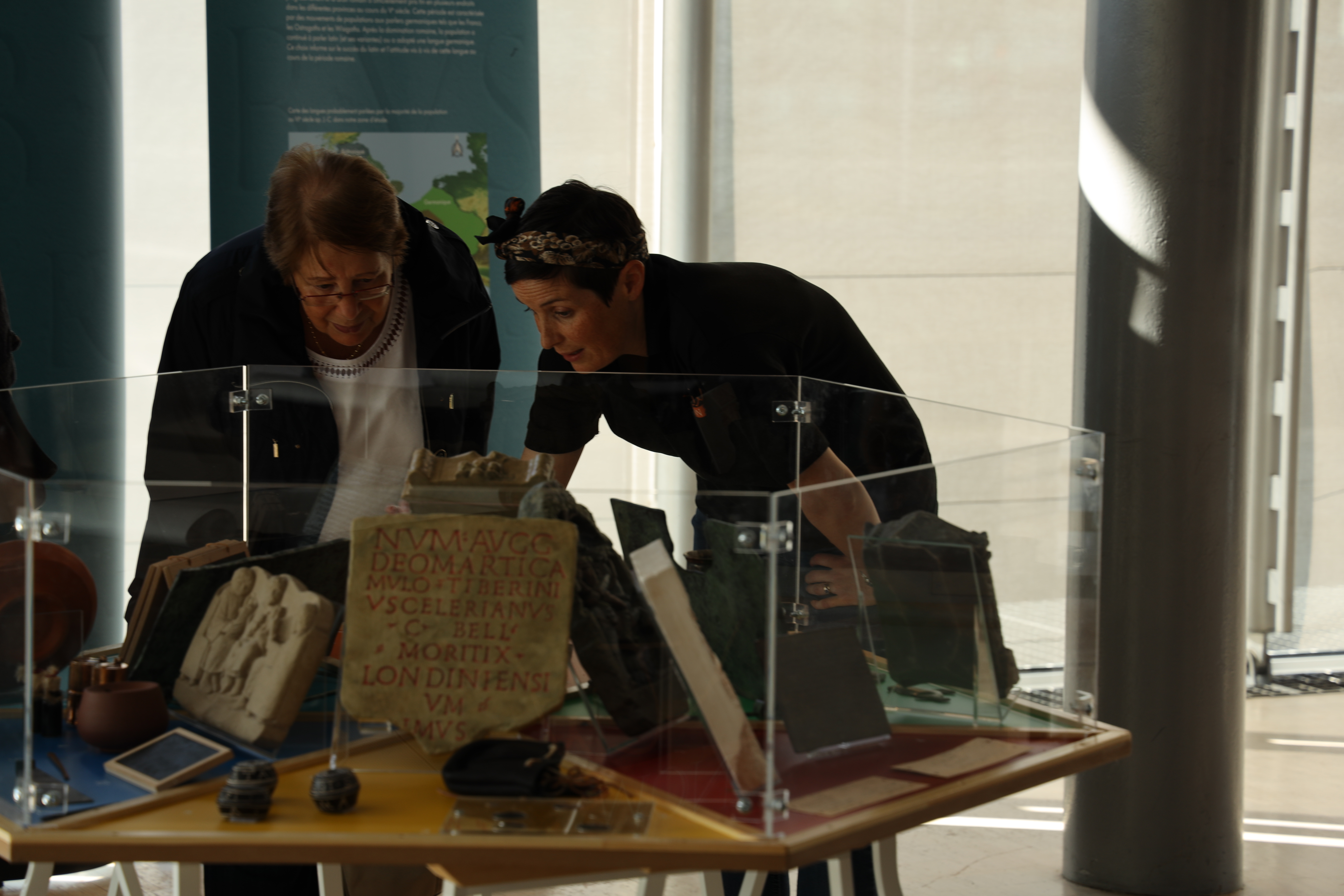

Next up for our post-‘Great-Merge’ database is to decide exactly how we can best make our data accessible for the general public and the academic community.